Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—A-bomb victims in photos: Retracing suffering at relief station located in school classroom

Jul. 14, 2022

Photos taken by Shunkichi Kikuchi in October 1945

Hagie Ota: “I was the only doctor. I wrote death certificates all the time”

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

Some photographs featuring Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bombing have clear information about the identities of people in the photos based on records or self-identification by the people themselves. If such photos and the personal accounts or testimonies by those who appeared in the photos can be linked, the horror unleashed by the use of nuclear weapons could be further brought into focus. Shunkichi Kikuchi, a photographer based in Tokyo who died at age of 74 in 1990, left behind many photos that can lead the way in that attempt. Mr. Kikuchi took a total of 860 photos in October 1945. By focusing on representative photos taken at a relief station and materials left by Hagie Ota, a physician appearing in the photos who died at the age of 96 in 2018, the Chugoku Shimbun takes a deep dive into the reality of the devastation.

In early October 1945, two months after the atomic bombing, Mr. Kikuchi visited Fukuromachi National School (now Fukuromachi Elementary School, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). The school’s ferroconcrete buildings escaped the fires arising immediately after the atomic bombing, and Mr. Kikuchi was able to enter to take photos. The school is located about 460 meters from the hypocenter. It is said that about 160 students, teachers, and school staff were at the school on August 6 and most were killed in the bombing.

The photos show straw mats covering the windows, whose glass was blown out by the A-bomb’s blast. At the school building’s entrance were placed a flag with a red-cross mark and a sign that read “Fukuromachi Relief Hospital.” Mr. Kikuchi went inside the school and snapped pictures. In a classroom in which mosquito nets were hung to protect admitted patients, Ms. Ota, who experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 23, was providing medical treatment to patients.

Ms. Ota also vomited and suffered headaches

When Ms. Ota was interviewed by the Hiroshima City Medical Association, she spoke of the shortages of staff and materials at the time. “All the classrooms lined up were used as hospital rooms. I was the only doctor there. I didn’t have a white hospital coat, though, and so I wasn’t viewed as a doctor,” as was reported in the book titled Hiroshima Ishi no Carte (in English, ‘Hiroshima physician’s medical charts’), published in 1989. Ms. Ota also was experiencing symptoms such as vomiting and a headache after the atomic bombing, but she persisted in her work of caring for patients.

Ms. Ota was born into the family of a physician living in the area of Ushita-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward) and, in 1942, graduated from the Imperial Women’s Medical College in Tokyo. After that, she worked in the ophthalmology department at the Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital. On August 6, she experienced the atomic bombing at her home in her neighborhood, about 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, before her commute to work. She left her home with a first-aid bag in hand and attended to neighbors who had suffered burns on their face or body. Her stock of drugs and medicine ran out in short order, however, because of the sheer number of wounded.

Her hospital, located in the area of Kako-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), which was located about 900 meters from the hypocenter, had been completely incinerated and destroyed in the bombing. Following directions from a hospital official, she took on the responsibility of providing first-aid in the area of Furuta-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward), starting on August 10, and at the Hiroshima branch of the Japan Kangyo Bank (in present-day Naka Ward), starting on August 15. In September of that year, she was transferred to Fukuromachi National School.

What she managed to do for patients was simply to rub a host of different disinfectants, such as mercurochrome and zinc oil, on their wounds. In another excerpt from the aforementioned publication, she explained how she “wrote death certificates all the time. I continued to report how many people died this day, how many people died that day.” In addition to severe burns that she was virtually unable to treat, she began to see more and more patients with hair loss and purple spots on their skin starting in late August. Victims lacking external injuries for the most part were starting to die one after the other. The symptoms they exhibited are now understood to be the result of radiation.

Ms. Ota also witnessed firsthand the public’s anger over the atomic bombing. In the beginning of September, when an overseas journalist entered the relief station, one woman mistook him for a U.S. soldier and exclaimed, “Why don’t you just take my child back to the U.S. and put him on display?” Her son, about 10 years old, had suffered burns over his entire body. The back of his head was torn open with the skull exposed, and he could only roll his body into a circle because he was unable to lie down.

Expressed anger in personal account

Listening to the mother’s plaintiff cry, Ms. Ota was overcome by anger. She wrote in a collection of personal notes titled Shokon II (in English, ’Scars II’), “How could they justify using such a cruel weapon on fellow human beings? It is absolutely unforgivable!”

Ms. Ota treated patients at Fukuromachi National School until around the spring of 1946. She later opened an optometry clinic in her neighborhood of Ushita-cho in 1948. She spoke at the World Congress of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW), held in Hiroshima in 1989, and argued that such a tragedy should never be repeated.

Late in her life, Ms. Ota lived in Chiba City, where her niece, Hisako Fujishima, 80, lives now. Ms. Ota died of lung cancer at the age of 96 in 2018. Ms. Fujishima donated the materials that Ms. Ota had kept at their home to the Hiroshima University Archives, based on the physician’s hope “that young people will learn that nuclear weapons must never be used.”

Mr. Kikuchi’s eldest daughter, Harumi Tago, 65, a resident of Nerima City in Tokyo, has held on to Ms. Ota’s letters to Mr. Kikuchi and his wife Tokuko, who died at the age of 93 in 2018, that referred to his photo of her.

While Ms. Ota managed her clinic, she sometimes displayed Mr. Kikuchi’s photo of the relief station around the time of August 6 each year and recounted her experience to the children visiting her clinic. Her letter to Tokuko shows her fondness for the photo. She wrote in a letter dated June 1996 that, “Even when I depart this world, the image will survive so long as Japan exists as nation.”

Part of the A-bombed school building of Fukuromachi National School, used as a relief station after the atomic bombing, has been preserved and turned into what is known as the Peace Museum. Mr. Kikuchi’s photos, including the one of Ms. Ota, are displayed in the museum. His photos continue to express Ms. Ota’s experiences and wishes to the people who come to visit.

--------------------

Kikuchi accompanied government team documenting devastation caused by A-bombing

Apologetic for photographing children

Mr. Kikuchi was born in Iwate Prefecture in 1916. After studying photographic techniques at a school in Tokyo, he joined the photography department at the company Tohosha, a propaganda organization founded by the former Japanese Imperial Army in 1941. His department gathered together leading photographers and published a pictorial magazine to communicate promote the military strength of the Japanese Army and Navy.

In September of 1945, Japan’s former Ministry of Education established the Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage, consisting of experts from a variety of fields. Nippon Eigasha, the company assigned to produce a documentary about the survey carried out by the committee, hired Tohosha to handle the photography work. In October of that year, Mr. Kikuchi traveled together with the documentary film crew of the committee’s medical team to take photos of Hiroshima.

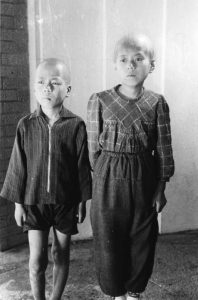

Mr. Kikuchi wrote in his personal account Genbaku wo Totta Otoko-tachi (in English, ‘Men who photographed the atomic bombing’), “I was confused many times during my photography work because people were using words I had never heard before, such as radiation and A-bomb disease.” He also took photos of children who had lost their hair from exposure to radiation and of the injured with obviously painful wounds that would not heal. He said he felt apologetic to the subjects of his photos.

In addition to the devastation of the city, a considerable number of his photos included signs of recovery, such as stand-up bars and local festivals. While Hiroshima citizens were unable to take photos themselves those days due to shortages of supplies and goods, Mr. Kikuchi contributed valuable photos that can help significantly fill the voids of information from that time.

Afterward, Mr. Kikuchi became a freelance photographer actively engaged in taking photographs of scientific experiments used in science textbooks. He died from leukemia in 1990. He had kept the photographic negatives of his Hiroshima photos on hand at his home. After he died, his wife Tokuko held on to the negatives. Starting in 2007, upon obtaining Tokuko’s cooperation, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Chugoku Shimbun set out about the work of digitizing the photos.

After Tokuko’s death four years ago, Harumi Tago, Mr. Kikuchi’s oldest daughter, inherited her father’s negatives. Ms. Tago hopes to discuss with the museum more about the process of archiving the negatives, because she believes they need to be stored at a facility with measures in place to prevent deterioration and ensure they can be passed down to future generations. “My father told me that he had sucked on salt while taking the photos in Hiroshima because there wasn’t much food. I want things belonging to Hiroshima to be kept in the city so they can be fully utilized,” she exclaimed.

--------------------

Devastation suffered by the city and public in Hiroshima in A-bombing are introduced on website

In January, the Chugoku Shimbun’s webpage added a new site of content, titled “Records of A-bombing disaster,” to the features section “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima.” The new site contains more than 100 photographs that capture the horrific conditions in the city destroyed by the U.S. military’s atomic bombing as well as members of the public who experienced the bombing.

Articles involving photographers and their photographs taken at that time will be gradually added to the site. The site will post feature articles and photos related to the series “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Photos from surveys of devastation,” published during the period April–May of this year, as well as other photos that have not appeared in the print newspaper. We invite everyone to access the site at the following URL: https://hiroshima75.web.app/ .

(Originally published on July 14, 2022)