Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Photos taken by U.S., Part 2: Smokestacks amid ruins

Nov. 1, 2022

Photos imbued with traces of daily lives lost

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

In the fall of 1945, the United States Strategic Bombing Survey team took photographs of a variety of smokestacks that remained throughout Hiroshima City. The United States appears to have used the photos to examine the way the structures had been damaged by the bomb’s blast depending on distance from the hypocenter. From the perspective of Hiroshima, however, the photos offer hints about the city before the atomic bombing as well as the devastation afterward.

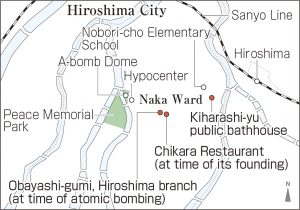

The U.S. survey team took one photo of the broken smokestack for the public bathhouse “Kiharashi-yu,” amid the ruins of the Nobori-cho area (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), located 1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter. Marehiko Nakano, 49, a music instructor who lives in the city’s Naka Ward, discovered the photo in question in a database of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum two years ago while conducting an online search. Mr. Nakano said, “My great-grandfather managed the bath. I was impressed that the photo is still around.”

Bunjiro Nakano, his great-grandfather, was born in Hiroshima Prefecture’s present-day Etajima City in 1896. Looking for work, he moved to Hiroshima City and founded the Kiharashi-yu public bath about 20 years before the atomic bombing. On the day of the bombing, August 6, 1945, Bunjiro was taking a morning bath. His remains were later found amid the ruins of Kiharashi-yu, which had been burned to the ground except for its smokestack. Believed to have been trapped under the collapsed building, he was 49 at the time of his death.

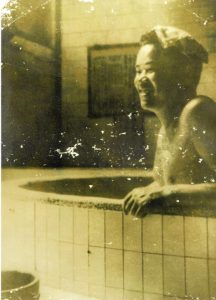

After having lost its owner, Kiharashi-yu was shut down. With his child attending Nobori-cho Elementary School, located near the former site of Kiharashi-yu, Mr. Nakano began the process of tracking the history of the area about three years ago. After asking his own father to search for any related photos, only one turned up. In that photo, Bunjiro is seen comfortably soaking in a bath at his own Kiharashi-yu.

Anticipating new information

Mr. Nakano donated the photo’s electronic data to the Peace Memorial Museum. The photo is now on display side by side with the U.S. team’s photo of the bathhouse smokestack at the museum’s New Arrivals Exhibition. He said, “I have mixed feelings when I think the photo of the structure was originally taken to investigate the destructive power of the atomic bombing. I hope viewers will compare the photo taken by the U.S. side with the photo taken before the bombing and come to the understanding that people’s daily lives, similar to our own today, were lost.” He also anticipates that additional information about Kiharashi-yu might be generated from elsewhere through the display of the photos in the exhibit.

More than 100 photos of smokestacks were taken by the U.S. survey team. The museum is now at work verifying the photos to identify which buildings the structures in the photos belonged to back then by looking at maps created before the bombing as well as other related information.

One photo drawing the museum staff’s attention is a shot taken of the Hondori shopping street (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), located about 500 meters from the hypocenter. When the smokestack in that photo was enlarged, letters appearing to read “Ka” appeared at top, with part of the letters “Ra” faintly visible on the structure under the first letters. With that, the possibility arose that the smokestack was part of a specific restaurant.

That restaurant is called “Chikara,” now located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. The chain of restaurants serves mainly udon noodles and is composed of 28 outlets, mainly located in the city. In 1935, the late Kakuzo Kobayashi, who originally hailed from Hyogo Prefecture, opened the first Chikara restaurant on the Hondori shopping street after having received permission to independently establish a restaurant from “Chikara-mochi,” an udon restaurant that originated in Kyoto. Mr. Kobayashi’s restaurant was located on the east side of the Hiroshima branch of Obayashi-gumi, a construction contractor, at the time of the atomic bombing, matching the location at which the smokestack photo was taken.

No materials remained at Chikara store

According to a book titled “Chikara hanjo-ki” (in English, ‘Chikara’s success story’), published in 1973, the restaurant became famous for udon and mochi (Japanese rice cake) from the pre-war period. The restaurant was deep, with 25 tables set up to serve about 100 customers. Just prior to the end of the war, Mr. Kobayashi had evacuated to a suburb of Hiroshima, based on the order that his restaurant was to be demolished to create fire lanes. In the aftermath of the bombing, he entered the center of the city and witnessed the devastation firsthand. With that, he gave up on the idea of restoring the restaurant immediately and returned to his hometown. In 1951, he was able to reopen in the area of Teppo-cho (present-day Naka Ward).

When Masaki Kobayashi, 66, a grandson and Chikara’s current president, who was born after the war, was given the chance to look at the U.S. survey team’s photo, he stared and said, “I’ve never seen this before.” Mr. Kobayashi explained that the company had no photos of the old restaurant before the atomic bombing. “Our first restaurant building constructed after the war had a chimney, so the restaurant before the bombing must have had one. Of course, the smokestack in the photo is likely to be that of Chikara, but it appears much larger than the one we had after the war.” It is also possible that the restaurant name could have been written on the smokestack of another building nearby as an advertisement for the restaurant.

This photo was likely taken by the U.S. survey team in routine fashion, but it now serves as important material that links the present-day Hiroshima City to its pre-bombed history.

(Originally published on November 1, 2022)