100 days until the Hiroshima Summit May 19 through 21: Summit in Hiroshima, at starting point for abolition of nuclear weapons

Feb. 8, 2023

Hope that visitors feel the terrible consequences of the use of nuclear weapons from the ground

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

Should even one nuclear weapon be used, what terrible consequences would result… Since the U.S. atomic bombing 78 years ago, Hiroshima, which became the first population center in human history to suffer the terrible consequences of the bomb, has consistently appealed to the world for the abolition of such weapons. Neither possession nor use of nuclear weapons by any country, including Russia which invaded Ukraine, is acceptable, and nuclear weapons must be abolished. February 8 marks 100 days until the opening of the summit meeting of G7 (The Group of Seven industrialized nations) in Hiroshima. The Chugoku Shimbun considers the significance of the fact that the leaders of the world’s leading nations, including the United States, the United Kingdom and France, all of which possess nuclear weapons, will gather together for the first time as the starting point for pursuing a peaceful future free of nuclear weapons.

Inhumane and long-lasting consequences

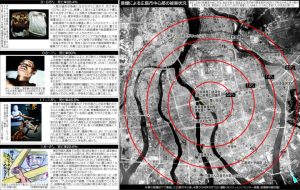

On August 6, 1945, the atomic bomb dropped by the US military exploded about 600 meters above Shima Hospital (now Shima Hospital of Internal Medicine located in the city’s Naka Ward) in the city center, 5.8 kilometers north of the main venue for the Hiroshima Summit, the Grand Prince Hotel Hiroshima, in Ujina-cho, Minami Ward.

Within two kilometers of the hypocenter, wooden structures were completely destroyed by the violent blast. Large-scale fires broke out due to the heat rays of the atomic bomb and the heat from fires inside buildings, including inside ferroconcrete buildings. According to a city survey conducted in August 1946, about 98% of approximately 45,000 houses and buildings within a two-kilometer radius of the hypocenter were completely destroyed or burned down, while about 92% of a total of about 76,000 houses and buildings in the city were partially or heavily destroyed or damaged.

Those who were near the hypocenter were burned black to the point that their skin was charred. Amidst the chaos, large numbers of dead bodies were incinerated without being identified. At the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound in Peace Memorial Park located in the city’s Naka Ward, the ashes of roughly 70,0000 victims are contained. As acute effects of radiation, such as bleeding, spread toward the end of 1945, those who escaped immediate death also succumbed.

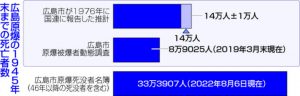

The City of Hiroshima generally estimates that 140,000 people (error: +/- 10,000) died by the end of 1945. In order to verify this figure, the city government has continued to conduct a demographic survey to collect and add various documents that contain the names of the victims. However, the number of those who have been identified as of the end of March 2019 was only 89,025. This probably results from lack of information regarding households whose family members were all killed and those who were from the Korean Peninsula.

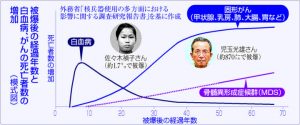

The effects of radiation continued in and after 1946. According to research by doctors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leukemia peaked 6 to 8 years after the atomic bombing, and its incidence rate among A-bomb survivors was four to five times that compared to those who were not exposed to radiation. After this period, cancers of the lung, stomach and other organs also increased. The increase in these cancers is considered probably due to genetic damage caused by radiation.

Since the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, an increase in cases of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which can easily lead to leukemia, has been pointed out. However, there are still many points that require further research on health effects from radiation, including radioactive “black rain” that fell after the atomic bombings.

Even with the single use of one nuclear weapon, various inhumane consequences will result. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimates that, among the G7 nations as of January 2022, nine countries possess a total nuclear stockpile number of 12,705, including 5,428 from the United States, 225 from the United Kingdom, and 290 from France. Russia, which was ousted from the summit in 2014, possesses the largest number at 5,977. In addition to possible intentional use by those in power, there is also the risk of cyberattacks and accidental explosions.

Motoujina-machi, where the leaders will gather for the summit meeting, is a place where many who were severely burned were brought after the atomic bombing and died one after another. The lives lost and the suffering of A-bomb survivors are carved into each and every town leading to Peace Memorial Park near the hypocenter. Hiroshi Harada, 83, an A-bomb survivor and a former Peace Memorial Museum president who lives in Asaminami Ward, says, “Just a short visit through the museum cannot fully convey the realities of the atomic bombing.” It is hoped that the world leaders will realize the need to abolish nuclear weapons on the grounds of the A-bombed city.

by Michiko Tanaka, Senior Staff Writer

Shingo Naito, 84, begins to share his A-bomb experiences of seven family members’ exposed to the atomic bomb

Testimony with determination to share “while I’m alive”

Hope for serious discussion toward a path of abolition

Shingo Naito, 84, an A-bomb survivor who lives in Minami Ward, Hiroshima, just began to share his experiences last spring. On August 6, 1945, seven members of his family were all exposed to the atomic bomb. Even today, he still vividly remembers what happened on that day and the following days; the last moments of his father who had burns over his entire his body, and the desperate and frantic appearance of his mother when searching for his younger brother and sister. His heart still aches when he thinks about the disquietude of each of them. Nevertheless, he is driven by his determination to share his experience “while I’m still alive,” because he is earnest in his desire that all inhumane weapons should be abolished.

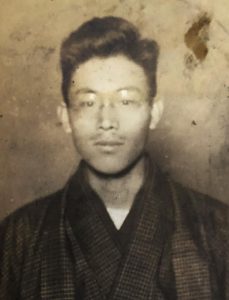

In the spring of 1945, Mr. Naito entered Nakajima National School (present-day Nakajima Elementary School in Naka Ward). There were seven in his family, including his parents, two elder brothers, a younger brother and a younger sister. “I had a very ordinary family. We all got along with each other, and we were happy.” He was living in Yoshijima-hagoromomachi (now part of Naka Ward), but in preparation for an air raid, his family evacuated to present-day Hatsukaichi City. His father Ryozo, then 45, who was working for the Hiroshima Communications Bureau (now the Chugoku Regional Office of the Japan Post), and his eldest brother Hideki, then 13, a first-year student at Sanyo Junior High School, however, remained at their home.

On August 5, the family gathered at their home for the first time after a long separation. Ryozo’s departure for his business trip was approaching in two days. The destination was Manchuria (present-day Northeast China). They dined together, prepared to bid an eternal farewell to him. On August 6, the day after the gathering, tragedy struck.

Mr. Naito’s two elder brothers left home early in the morning. Hideki was sent to Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward) near City Hall to help create a firebreak to prevent the spread of fire in case of an air raid. His second elder brother Takahiro, then 9, headed for Nakajima National School. Mr. Naito was at home and playing with his younger brother Mutsuo, then 4, and his younger sister Kumiko, then 2, on the veranda-like porch of their house.

At one point, Mr. Naito spotted a crab near an air-raid shelter in his yard and went close to it. He was blown into the shelter. When he timidly stepped out, he found his father standing in a daze in the yard. He suffered burns over his entire body. His mother Sueko, then 39, was atop their collapsed house. Mr. Naito was startled by her dreadful appearance looking like a demon. She was tearing off the roof tiles, and with her hair in complete disorder. Finally, she came down from the heap with his blood-covered younger brother and sister in her arms.

As the flames approached, the family headed for the Army’s Yoshijima Army Airfield (now part of Naka Ward). His father barely managed to walk. When Mr. Naito tried to take him by his hand, the skin peeled right off. When they got to their destination, his brother and sister were no longer breathing. His father, who had collapsed, died on August 10. “Long live the Emperor,” were his last words.

Mr. Naito’s two elder brothers also died in the atomic bombing. He met his brother Takahiro miraculously on the 11th, and went to the place where their family had evacuated. His brother, however, took his last breath at a hospital on August 30, where he had been admitted. During his brother’s last moments, Mr. Naito did not enter the hospital room. He said with his head down, “My mother called me. But I pretended not to hear her, although I know that it was coldhearted.” He was just six years old. He could no longer endure to see another family member die.

His eldest brother Hideki died on August 14. After the bombing, his mother frequently went to the city center from where they had evacuated. One day in September, she came back with a dated box containing Hideki’s remains inside. “I let him die alone,” she said and cried.

Mr. Naito cannot forget his mother who worked so hard for the family after the war. Although she was small, she was engaged in manual labor at a factory, sending him to a private junior high school. However, she frequently looked ill probably due to her exposure to the atomic bomb. In 1953, when she returned home from work, she suddenly passed away. She was 47 yeas old. Mr. Naito was left all alone when he was a third-year junior high school student.

After graduating from high school with support from his relatives, Mr. Naito started working at an electric power company. He married and was blessed with three daughters. He was over 80 years old when he began to share his memories that had been kept secret from his family. He realized that when looking back on his life he would not able to avoid that day forever. He also said that his parents encouraged him to share his experiences when they appeared in a dream.

On August 6, 2022, Mr. Naito found himself with an unexpected, remarkable opportunity. As an A-bomb survivor, he met with U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres who attended Hiroshima City’s Peace Memorial Ceremony. The U.N. adopted its first resolution in 1946 calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction. Nevertheless, many countries still cling to nuclear weapons, and Russia, which invaded Ukraine, has even hinted at the use of nuclear weapons. Mr. Naito made a proposal to Mr. Guterres about organizational reform of the United Nations, which cannot break the deadlock due to strong authority of the nuclear weapons states.

Prior to the G7 summit meeting, Mr. Naito is urging the world leaders to visit the Peace Memorial Museums located in city’s Naka Ward and listen to the voices of the A-bomb survivors. He says, “If they just show off their solidarity, Russia and China will respond strongly against them. Unless they touch on the actual consequences of nuclear weapons and think about a path toward a peaceful world seriously, there is no significance to holding the summit meeting in Hiroshima.” What he would like to hear from the leaders is their genuine determination toward the abolition of nuclear weapons.

**

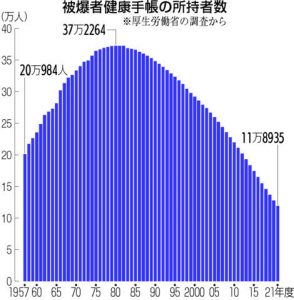

Little time left to listen to the voices of A-bomb survivors as the number of health book holders is less than one-third of its peak

The survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have shared their painful memories suffering the physical and emotional toll, driven by their absolute desire that “No one else should suffer as they did.” Time left to listen to their actual voices is limited. According to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the average age of the A-bomb survivors was 84.53 in fiscal 2021 (as of the end of March 2022). The total number of A-bomb survivors is 118,935, less than one-third of its peak (372,264) in fiscal 1980.

The term “A-bomb survivor (Hibakusha)” used for indicating the figures above, refers to those who possess an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate in accordance with the law. Under the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, A-bomb survivors are classified as follows: 1) those who directly survived the atomic bombing in the specified neighboring areas at the time of the bombing; 2) those who entered areas within the range of two kilometers of the hypocenter within two weeks of the atomic bombing; 3) those who were affected by radiation for reasons such as relief efforts; and 4) those who were in-utero of a person who satisfied any of 1) to 3) in those days. Certificate holders are eligible to access the central government’s relief measures, such as free medical care.

There are many people who have complained about their health after being exposed to radioactive “black rain” that fell in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. After a class action lawsuit, the central government reviewed its guidelines. The government began issuing certificates to those whose exposure to the black rain that fell after the atomic bombing cannot be denied and who are suffering from certain diseases as of April 2022.

Those who suffer from the consequences of the atomic bombing are not limited to those who possess an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. For example, there are an estimated 2,000 to 6,500 atomic bomb orphans who lost family members while being evacuated to the outskirts of the city and countryside in accordance with government policy. There are also second-generation A-bomb survivors who are worried about their health although genetic effects on health have not been scientifically proven.

Layout: Kazuma Sugihara

(Originally published on February 8, 2023)