Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima—Recreating cityscapes: Riverbanks lined with cherry trees was relaxing space for patients at nearby hospital

Dec. 27, 2021

Daughter of nurse at No. 2 Army Hospital in Motomachi holds on to mother’s photos

Hospital turned into hellish inferno with many wounded

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

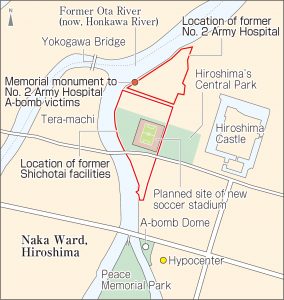

Motomachi (located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), with Hiroshima Castle, and its surrounding areas served to symbolize Hiroshima as a “military city,” with facilities related to the former Imperial Japanese Army concentrated there. Hiroshima’s Central Park, the planned construction site for a new soccer stadium, was once the location of the Chugoku District transport soldier recruitment unit (known as “Shichotai” in Japanese). The A-bombed remnants of the unit’s facilities were unearthed at the site in 2021. On the north side of the Shichotai facilities was located the Hiroshima No. 2 Army Hospital. Reiko Yamaguchi (née Kohara), who died in 2015 at the age of 87, used to work as a nurse at the hospital. Her daughter has held on to her mother’s photographs taken on the hospital grounds as a keepsake of her mother.

In one of the photos, 17-year-old Ms. Yamaguchi poses with a gentle expression on her face on a tree-lined avenue along what was then known as the Ota River (now, the Honkawa River). Behind her is a sign that reads “Location for Patient Evacuation.” The triangular roofed structures in the right rear of the photo are temples in the area called Tera-machi, according to the staff at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster indicates that, “The long riverbanks lined with cherry trees were beautiful, offering great spots to fish and walk for the patients at the hospital.” Another photo of her smiling with two colleagues on a bench reveals the Yokogawa Bridge behind them.

Ms. Yamaguchi was originally from the present-day town of Hohoku-cho, part of Shimonoseki City in Yamaguchi Prefecture. According to documents in possession of the Yamaguchi Branch of the Japan Red Cross Society, she was assigned to work in the tuberculosis ward of the army hospital as a member of the “No. 715 first-aid corps” in October 1944. In conjunction with the opening of a hospital branch in Miyoshi City in Hiroshima Prefecture, she was transferred there on July 22, 1945.

She spoke of her experience only once

On August 6, half a month after Ms. Yamaguchi’s transfer, Hiroshima was devastated in the atomic bombing. On the following day, Ms. Yamaguchi traveled to Hiroshima from Miyoshi City to engage in rescue operations. Many of the 330 hospital staff and 750 patients had been killed at the hospital, located about 800 meters from the hypocenter. Numerous wounded were brought to a makeshift first-aid center built of straw mats and corrugated metal sheeting on the riverbank. Even after returning to Miyoshi City, she remained engaged with the work of caring for A-bomb patients brought there from Hiroshima.

After the end of the war, she married and lived in Tokyo. Tomoko Bessho, 60, Ms. Yamaguchi’s oldest daughter who lives in Machida City in Tokyo, said, “My mother didn’t tell me about her experience in Hiroshima until the end of her life.” Ms. Bessho said she was busy in her work related to drug development at a pharmaceutical company and was not very interested in hearing about her parent’s experience in the war.

Eleven years ago, Ms. Yamaguchi spoke of that history only once when Ms. Bessho’s daughter, now 23, then a sixth-grader in elementary school, asked her grandmother about her experiences in the war for a school assignment she was doing. Ms. Yamaguchi conveyed to her granddaughter about how she had attended to dying patients lying on the riverbanks while catching naps when possible next to them. She also explained that one of her wounded patients had asked her for water and died soon after she had poured it into the person’s mouth. She also witnessed soldiers collecting corpses and burning them on the banks of the river. “There is no more miserable death than theirs. It was so heartbreaking,” she said.

For Ms. Bessho, it was the first time for her to hear about her mother’s situation at the age of 17. To follow her mother’s footsteps from those days, Ms. Bessho began to visit Miyoshi City in Hiroshima and Yanai City in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where her mother had worked for a time, to gather relevant materials and accounts. She found the photos in an old photo album and investigated on her own where the photos had been taken.

The psychological scars that her mother had kept to herself were far deeper than Ms. Bessho had imagined. When she shared with her mother the information that she had gathered, Ms. Yamaguchi expressed anger. “What on earth do you want to do with that?” she asked her daughter. Finally tired out from crying, her mother slept. With that experience, Ms. Bessho began to worry about, and doubt, the meaning of passing down A-bombing memories to future generations. One A-bomb survivor she got to know, however, encouraged her. “I hope you don’t stop trying to know more about your mother’s experiences,” she had said. Those words gave Ms. Bessho new hope.

Today, all high-rise condominiums

On the day of the atomic bombing, the area along the Honkawa River was turned instantly into scenes of a hellish inferno. Following the end of the war, however, it became a densely populated residential area also known by the nickname “A-bomb slum.” Later, the area residents were evicted as a result of a city redevelopment project, which transformed the living space there into Motomachi high-rise condominiums. Walking trails and cherry trees returned to the banks of the river, becoming a spot of relaxation for citizens.

On August 6 every year, Ms. Bessho visits the banks of the Honkawa River, where a memorial monument was erected to the A-bomb victims at the No. 2 Army Hospital, to attend the memorial service held on the site. She explained, “My mother attended to many wounded people on their deathbeds. One nurse was killed in the atomic bombing after having been assigned to the hospital as a replacement for my mother after her transfer to Miyoshi City. I offer silent prayers for the lives that were lost here.”

(Originally published on December 27, 2021)