Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing—Photos of A-bombing destruction, Part 9: Father and son in front of firewall captured by Shinzo Ishikawa

Dec. 14, 2021

Photos include newly discovered record of school building damage wrought by A-bombing, group photo of students taken before bombing

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

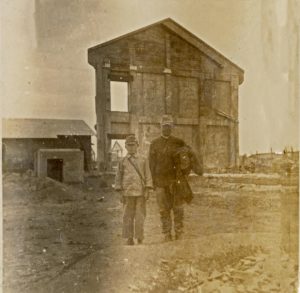

An imposing firewall remains standing among the burned ruins of an incinerated wood building. With their backs against the unusual wall, Shinzo Ishikawa (who died at age 83 in 1986) and his oldest son Masami (who died at age 85 in 2019), standing side by side, are captured in a photograph. The photo in question was discovered in Mr. Ishikawa’s photo album, which was donated two years ago to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward.

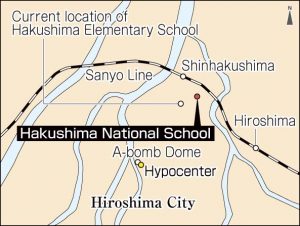

According to the museum’s analysis, the photo seems to have been taken at the location where Hakushima National School (now Hakushima Elementary School, in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward) once stood. The school was located about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. About 100 students were instantly killed at the school in the bombing. Although the school building was incinerated, the fireproof firewall, used to prevent the spread of fires, remained standing. The museum’s curators are in the process of investigating when the photo was taken but estimate it was during the period between the fall of 1945 and the summer of 1946, based on comparisons made with other photos archived at the museum.

In notes, descriptions of city in chaos

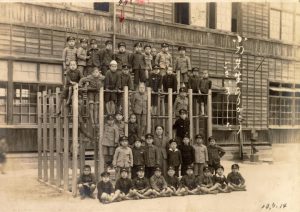

The school was near their home. Mr. Ishikawa had opened a photo studio in the area of Hakushimanaka-machi (now part of Naka Ward) in 1930. His main business involved taking photos upon request by schools, which meant he had a chance to take group photos for the Hakushima National School, where his son was a student. In August 1943, he was recruited to work at the Japanese Navy’s shipping department in Kure City and moved to military housing there. Starting the day after the atomic bombing, he entered Hiroshima City as a member of the shipping department’s rescue team.

Mr. Ishikawa, then 41, later wrote notes describing the chaos of the destroyed city. “When many victims, including children, found out we had arrived as the rescue team, they rushed to our vehicle and flocked around us, desperately calling for help,” he wrote. He also witnessed the scene of a child hanging onto their dead mother.

Six members of his family, including his wife and Masami, then a sixth-grader at the national school, were able to avoid the disaster given that they were at a wartime evacuation residence outside the city. However, the area surrounding their home in Hakushima had suffered severe damage in the bombing. After the war ended, Mr. Ishikawa resumed his photo studio business at a different part of Hiroshima. He reengaged in the work of taking school photos and in his later years, he sorted the photos he had taken and kept on hand and pasted them in the photo album.

“Since I was a child, I saw my grandpa treat the album with great care. He held out hope that even one of the photos would prove useful,” said Yumi Nakasuga, 58, Mr. Ishikawa’s granddaughter who lives in Habikino City, Osaka. Ms. Nakasuga donated Mr. Ishikawa’s photo album to the Peace Memorial Museum in 2019. Her decision was prompted by the death that year of her father, Masami, who had taken over her grandfather’s studio and belongings.

More than 100 photos included in the album

Before the album’s donation, Mr. Ishikawa had not been included in the group of photographers of A-bomb photos known to the museum. But his album contained more than 100 photographs taken in Hiroshima before the atomic bombing and all the way through the post-war period. Many of the photos offered no clues as to the time and location of the photography. Amid that uncertainty, the museum’s curators worked to verify each one of the photos in detail.

As a result of the analysis, it was found that three of his photos, including the one of the firewall, were to that point unverified images taken in Hiroshima early after the atomic bombing. The locations where the photos had been taken were also identified, such as the site of the former Hakushima National School. For now, the museum considers that Mr. Ishikawa took the images of himself by setting up the camera in front of him, thereby classifying Mr. Ishikawa as the photographer of those photos.

The museum also confirmed that Mr. Ishikawa’s collection included a group photo with school children he had taken before the atomic bombing. The photo skillfully blends playground equipment with the children’s facial expressions. The museum now displays photos of the school taken both before and after the atomic bombing side by side in its new arrivals exhibit, along with the words Mr. Ishikawa wrote in his album, which read, “A single atomic bomb had turned Hiroshima to ash.”

Last month, Ms. Nakasuga visited the exhibit and smiled when she saw it. “I think I was able to show my gratitude to my grandfather by donating his photos to the museum,” she said. Makoto Ishikawa, 57, Ms. Nakasuga’s brother who lives in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward, accompanied her and gazed at the photo taken in front of the firewall. “I can see how the children’s school building was heavily damaged in the atomic bombing. I assume my grandfather tried to keep hold of the photos, with their clear message, based on the pride he felt in his work.”

With A-bomb survivors and their surviving family members growing elderly or dying, it is not unusual for the next generations to inherit such photos and albums. If the photos can be analyzed in detail without being dispersed or lost, they could be utilized as new materials that speak to the reality of the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on December 14, 2021)