Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing—Photos of A-bombing destruction, Part 6: Captured by Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory’s Isao Kita

Dec. 10, 2021

With observation as “mission,” Mr. Kita continued recordkeeping and kept reports, evading censorship

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

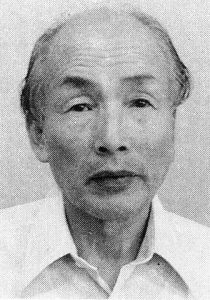

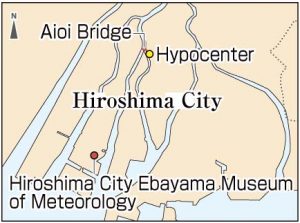

In a room at the Hiroshima City Ebayama Museum of Meteorology, located in the city’s Naka Ward, a curator removed five photographic negatives from a storage container. The images were left behind by Isao Kita, who died in 2001 at the age of 89 after working at the Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory (now the Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory), which was once housed in the same building as the museum.

The images show Aioi Bridge (now in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), whose sidewalks were raised by the blast from the atomic bombing, the collapsed Tsuruhane Shrine (now in the city’s Higashi Ward), and a fence situated along railroad tracks (now in Nishi Ward) that had spontaneously combusted due to thermal rays from the atomic bombing. The images were taken between the end of August and late September 1945 during a survey of A-bomb destruction carried out by the meteorological observatory and donated to the Museum of Meteorology by Mr. Kita’s bereaved family after his death.

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Kita, who was 34, was working at the meteorological observatory, located on the summit of Ebayama Hill (37.6 meters above sea level), about 3.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. The A-bomb blast that followed the flash of light hit the unshielded meteorological observatory. Looking back on the plight of the observatory at that time, Mr. Kita wrote years later, “Many of the staff were wounded, had their homes burned down, and lost family members.” Amid an increase in number of absentee workers, he reported it to be “extremely difficult to continue weather observation continuously day and night.” Nevertheless, the facility continued to record weather conditions “based on a sense of mission that they were not to miss any observations,” according to his writings.

Walking in and around the city

Despite persistent shortages of personnel and supplies, the staff at the meteorological observatory worked hard in late September on a survey conducted by the meteorological arm of a special committee established by a national research council of Japan’s former Ministry of Education to survey the devastation caused by the atomic bombing. Mr. Kita participated in the work by walking in the city and the surrounding towns and villages and recording the damage to buildings and the conditions under which “black rain” had fallen after the atomic bombing. He also took photos of the damage caused by the Makurazaki typhoon, which took the lives of more than 2,000 people in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Regarding his documentary photography, Mr. Kita explained that he had taken at least three rolls of film, or 36 photos, including ones taken before the survey, but that the first two rolls had been lost (as reported in the Chugoku Shimbun in 1978). Of the five photographic negatives remaining at the Museum of Meteorology, the shot of the burned fence is believed to have been from the early rolls of film and is likely a reproduction.

Reports published after end of Allied occupation of Japan

Whether the series of survey reports could be published was unclear due to censorship rules applied under the Allied occupation. In 1947, Mr. Kita made mimeographed copies of the reports with the aim of at least releasing the information on weather conditions. The reports were confiscated by the occupation forces, but some were secretly left behind. Officially, the reports were incorporated, along with photos, into the Collection of Reports on the A-bomb Damage, published in 1953, the year following the official end of the Allied occupation of Japan.

In 1951, a job transfer took Mr. Kita to Kochi Prefecture. He subsequently worked at a number of meteorological stations throughout western Japan and at the Osaka District Meteorological Observatory before returning to the Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory in 1967. After retiring in 1972, he continued to work for an organization affiliated with the Hiroshima prefectural government involving environmental research.

Mr. Kita’s third son, Nobuhiko, 74, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward, remembers his father continuing to observe temperatures and rainfall outside in the yard of his home until his death. He said, “The accumulation of such records one by one can be used to connect to future generations. The attitude of an observer had been drilled into him.” Mr. Kita had remarked that photography was his obligation to the victims. Nobuhiko recalled, however, that “It seems to me it was more a case of being his professional career involving the work of observation.”

The Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory moved into the Hiroshima consolidated government offices building, located in the city’s Naka Ward, in 1987. In 1990, management of the building was transferred to the Hiroshima City government for preservation, and in 1992, the building reopened as the Japan’s first museum dedicated to meteorology. An article reporting the opening of the museum indicated that Mr. Kita was pleased about the facility’s rebirth.

Mr. Kita had said, “I was always worried that the building would be torn down at any moment, but it was given a role worthy of the building’s history.” The photographic negatives conveying his desire to pass on the records, which was only fulfilled in his later years, are now preserved in the very place Mr. Kita used to work.

(Originally published on December 10, 2021)