Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Photos of devastated city taken by U.S. provide new insight

Oct. 30, 2022

G7 leaders called on to grasp devastation from nuclear weapons by comparing aerial photos of summit site, one taken 5 months after bombing

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

The United States took many photographs in their attempt to survey the unprecedented destructive force of the atomic bomb, which that country had detonated over Hiroshima in the world’s first use of such weapons on a civilian population. Many of the photos, including aerial photographs of the devastated city, are not recorded in the photos of that time taken by Japan. Amid mounting concerns about Russia’s possible use of nuclear weapons, the summit meeting of the G7 (Group of Seven industrialized nations) is scheduled to be held in Hiroshima next May, in 2023. That opportunity should be fully utilized to communicate to the world the indescribable tragedy resulting from the use of nuclear weapons. The photos taken by the United States convey the story of the lives lost in the incinerated city ruins and the suffering of A-bomb survivors.

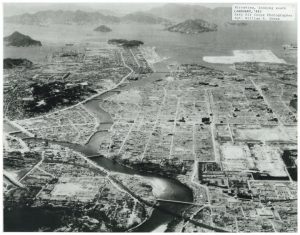

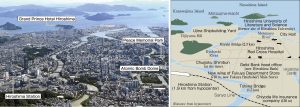

At the National Museum of the United States Air Force, located in the Midwestern state of Ohio, one photo captures a wide swath of the fire-ravaged remains of Hiroshima around five months after the atomic bombing. It was taken by the U.S. military from the sky, looking to the south and capturing the area to the east of the hypocenter. In the rear of the photo, away from the devastated city center, is the area of Motoujina-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), the location of the Grand Prince Hotel Hiroshima, which is a candidate site as the main venue for the G7 summit. The photo, the electronic data for which was obtained by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum six years ago, is useful for comparisons of that area then and now.

Experienced A-bombing while working at Ujina Shipbuilding Yard

In the vicinity of the present-day hotel stood the Ujina Shipbuilding Yard, established in 1919, which was engaged in the building of military vessels during World War II. By August 1945, its employees had been mobilized as a workplace volunteer corps and helped, by turns, in demolition work for the creation of fire lanes in preparation for potential air raids by the United States.

Takeshi Madaraishi, then 17 (who later died in 2019), was working at the Ujina Shipbuilding Yard at the time. In an account of his experience written in 1989, he provided detailed descriptions of how all his co-workers had been killed in the atomic bomb while being mobilized for such work.

According to that account, Mr. Madaraishi, who was originally scheduled to work with the corps on August 7, was reading a publication about naval architecture on August 6 at his workplace, located in Motoujina-machi, about five kilometers from the hypocenter (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). After an intense light flashed outside, glass from windows were scattered by the bombing’s blast with a sharp clatter. When looking outside, he saw something “like a red thunder cloud” that continued to grow ever larger.

On that day, about 160 employees had been mobilized to the former Tenjin-machi area, located to the south of present-day Peace Memorial Park, approximately 500 meters from the hypocenter. A relief party that Mr. Madaraishi had joined headed by truck to the work site of their colleagues but was unable to move beyond Miyuki Bridge due to flames arising in the direction of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. With that, the group changed course and traveled up the Motoyasu River on one of the shipyard’s boats, arriving at the river bank near the work site around 11:00 a.m.

“Everyone was burned all over by thermal rays from the bombing. Their skin color had changed to bright red and darkened into the color of a vegetable (carrot).” When the rescue party found their co-workers among the many wounded, they worked to grab their bodies to place them on stretchers but their skin would just peel off. Although 35 employees were rescued, they died either on the boat or at the yard after they had been brought back. The bodies were cremated in an open area on the shipyard grounds. The rescue party continued its search for missing employees until August 11, but many were never found.

Mobilized father never returned home

Kaoru Fujinaga, 80, an A-bomb survivor who is now a resident of Funabashi City in Chiba Prefecture, lost his father Asato, then 44, who had been working at the Ujina Shipbuilding Yard at the time. Mr. Fujinaga’s family was composed of eight people: his parents and six brothers and sisters, including Mr. Fujinaga, who was three years old at the time. The family had a home in the area of Motoujina-machi.

“I heard that my father had a gentle nature and helped out the neighborhood association. On August 6, before breakfast, he took me to a nearby family gravesite. That is the only memory I have of him.” The remains of his father, who left home to help in work for the war effort, were never found.

His sister, Kazuko, then 12 and in her first year at Hiroshima Municipal Third National School (now Midorimachi Junior High School, in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), was also mobilized for building demolition work at a site near Hiroshima City Hall, about one kilometer from the hypocenter, with her classmates. His mother Ayano, who died in 1989, searched for Kazuko carrying her son, Kaoru, on her back, ultimately finding her in a crowd of wounded near the Miyuki Bridge when Kazuko called out to her mother. Nevertheless, Kazuko’s head area was severely burned and she died on August 28.

The five remaining children, and their mother, had lost their father, the breadwinner of the family. “We were forced to live a tough life. Numerous times my mother apparently thought about committing suicide all together, as a family.” Ayano took care of her children by working for a subcontractor in the shipbuilding yard. Kaoru worked part-time delivering newspapers starting when he was in the second grade of elementary school until the third grade of junior high school to help with the family’s income.

Working as a taxi driver, among other jobs, Mr. Fujinaga has also been involved over many years in the activities of an A-bomb survivors’ group in his home of Funabashi City. “Even those who survived the A-bombing have experienced hardship after the war. We should never use violence to resolve our problems. It is outrageous to engage in war and use nuclear weapons.” Mr. Fujinaga hopes that the G7 leaders and heads of other nations who visit Hiroshima take that lesson to heart.

------------------------------------

Peace Memorial Museum enhances efforts to collect photos, including those in color, taken by U.S.

The filming of Hiroshima by the U.S. military began in earnest with the expansion of the occupation forces on to the mainland after Japan signed the instrument of surrender on September 2, 1945. Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a volume published by the city governments of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1979, points out that the aim of the United States was to create materials related to national defense and strategic decisions based on thorough investigation of the military effectiveness of the atomic bombing.

The United States Strategic Survey Team, numbering 1,150 people who surveyed the effects of the aerial bombardment of Japan during the war, placed a particular focus on the Hiroshima atomic bombing. More than 1,000 photos that reveal the condition of destroyed buildings and bridges were taken in October and November 1945. Some of the photos were used to record the effects from the atomic bombing on the human body for military surgeons. The photos included some in color, which were rare at the time. Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Museum has in recent years placed an emphasis on collecting photos related to the atomic bombing that have been archived in the United States. They sent curators to the United States during the period 2016–2019 to obtain electronic data of the photos held by 12 organizations, including the National Museum of the United States Air Force. The museum also interviewed photographers who were still alive.

Occasionally, new information is obtained from someone who comes forward to claim that a person appearing in a well-known photograph might be them. There was a photograph of a boy, for example, whose face and neck were burned by the bombing’s thermal rays but not his head because it had been covered by a cap at the time of the bombing. In 2004, Shigeo Kambara, 94, a resident of Fukuyama City, contacted the museum and identified himself as the boy in the photo.

Mr. Kambara, 17 at the time of the bombing, was a special cadet in the former Army Marine Transport Unit. He was exposed to the thermal rays on the school grounds of the Senda National School (now Senda Elementary School, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), which served as a military billet at the time. The school was about 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. His face, neck and left leg were severely burned. He suffered acute pain in his left ear, a wound that became infested with maggots. In the fall of 1945, American soldiers came to the hospital in Hiroshima where Mr. Kambara had been admitted and made a photographic record of him.

In 2006, Mr. Kambara donated the account of his A-bombing experience to a local A-bomb survivor group, which was engaged in the compilation of A-bombing memoirs and the like. Explaining the horrible spectacle of people with burns much worse than his own, he called on all countries in the world to act to abolish nuclear weapons so that “such a tragedy is never again repeated.” Even with those photos kept by the United States, the country that used the atomic bombs, it is necessary to face up to the experience and thoughts of the A-bomb survivors who played the role of subjects in the photos.

(Originally published on October 30, 2022)