Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Photos taken by U.S., Part 4: Teacher’s nameplate

Nov. 3, 2022

Continued to mourn students killed in atomic bombing

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

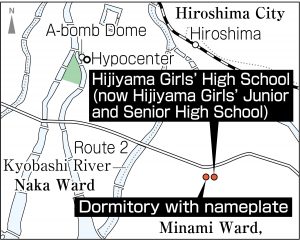

The letters written in black ink on a nameplate made of paper were burned away by thermal rays from the atomic bombing, leaving only holes. The words “The Nii residence,” however, could still be made out. The nameplate represents one of the materials related to the atomic bombing that were repatriated to Japan by the United States in 1973. It was from a school dormitory in the area of Asahi-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), located about three kilometers from the hypocenter. The nameplate reveals how extensive the impact of the thermal rays was at the time of the bombing.

The nameplate belonged to the late Michiko Nii, an English teacher at Hijiyama Girls’ High School (now Hijiyama Girls’ Junior and Senior High School, in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward). In 1973, a former student of Ms. Nii’s saw a photograph of the nameplate in a Chugoku Shimbun article and provided information to the newspaper.

After receiving the news, the paper interviewed Ms. Nii. According to the article based on the interview that appeared in the June 6, 1973, edition of the newspaper, she was 29 when she experienced the atomic bombing in a dormitory to the west of the school. The dormitory had originally been a private dwelling that the school was renting at the time. She noticed that the nameplate, which she had written on a piece of paper she kept on hand, had been burned in the bombing and she took it to her school. She conveyed how the late Tamazo Kuninobu, who was school principal at the time of the atomic bombing, showed it to the Allied Occupation Forces when they came to survey the A-bombing’s destruction around October 1945.

Because not enough information was able to be gleaned about Ms. Nii from the previous article alone, this reporter paid a visit to Yasuko Yamaguchi, 89, a resident of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward who originally provided the paper with the information about Ms. Nii as her former student. “I lived with Ms. Nii until I graduated from high school,” said Ms. Yamaguchi as she described life with her teacher after the war.

Life together in dormitory

Before the atomic bombing, Ms. Yamaguchi’s family ran a timepiece shop in the area of Horikawa-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), in the center of the city. She was 12 years old and a first-year high-school student at the time of the atomic bombing. She survived because she had been at school, but her parents and grandmother, who were at home, were killed when the combined home/shop was destroyed in the bombing. Her two older sisters were also killed.

Many students who lost families or homes in the atomic bombing were unable to return to school, but Ms. Yamaguchi had the strong desire to make it back. She was able to return to Hijiyama Girls’ High School in February 1946 with the support of relatives who lived outside of the prefecture and assisted in paying her tuition. The school entrusted Ms. Nii with supporting Ms. Yamaguchi, and the two began to live together in the school dormitory.

“I went to school in a khaki-colored uniform that Ms. Nii had made from a military uniform,” recounted Ms. Yamaguchi. At times when food was scarce, Ms. Nii traded her own kimono garments for food. On the other hand, Ms. Yamaguchi would have to run and call a doctor numerous times because Ms. Nii would frequently fall ill and become bedridden.

After graduating from high school and working in Osaka, Ms. Yamaguchi applied to get into Hiroshima University at the age of 22 with the aim of becoming a teacher herself. Ms. Nii was working at Otake High School in Otake City at the time. She borrowed textbooks from her workplace to give to Ms. Yamaguchi for use in her studies. Ms. Yamaguchi passed the entrance exam and became a student at the university. After graduating, she worked in the field of education for visually impaired children.

Condolences expressed in written account

Toward the end of her life, Ms. Nii lived in a nursing home for A-bomb survivors in Nagasaki City. Ms. Yamaguchi helped get her into the facility because Ms. Nii was single and living alone. With Ms. Nii dying from heart failure at the age of 73 in 1989, Ms. Yamaguchi was contacted by the home and as a result was able to be with Ms. Nii at her death. Ms. Yamaguchi said that Ms. Nii expressed her gratitude repeatedly to her at that time.

“Ms. Nii helped me so much,” said Ms. Yamaguchi. Influenced by Ms. Nii, who was a Catholic, Ms. Yamaguchi decided to undergo baptism. She became involved in the compilation of A-bomb accounts that were published by the Hiroshima Catholic Council for Justice and Peace in 1991. She contributed her own account to the collection about the atomic bombing and her life after the war.

As for Ms. Nii’s writings, the only one ever found was in the third edition of accounts of A-bomb experiences published by the nursing home in 1985. Ms. Nii wrote about her feelings of sorrow about her students who had died in the atomic bombing. Many of the students at Hijiyama Girls’ High School had been mobilized to work at military facilities, with 73 students and two instructors ultimately dying in the bombing.

Her written account read, “Their deaths were so tragic I cannot endure the sorrow. I can only pray that their souls will rest in peace.” When I saw the words “The Nii residence” on the nameplate burned in the atomic bombing, my thoughts turned to the life of the teacher who supported a student forced to endure great hardship and continued to mourn the lives lost in the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on November 3, 2022)