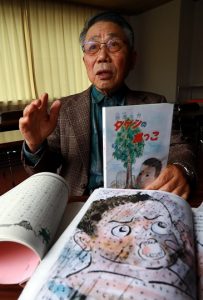

Hiroshima Voices: “No Nukes, No War” Takeshi Kawai, 85, A-bomb orphan, Hofu City, Yamaguchi Prefecture

Mar. 29, 2023

War is most miserable for children

When Takeshi Kawai was seven years old he was orphaned after losing three members of his family in the atomic bombing. His father, who was severely wounded in the bombing, sank to the bottom of a river and drowned as the two were trying to cross and flee to safety. Even today, that memory of his father’s death brings tears to Mr. Kawai’s eyes. After turning 60, he began sharing his experience at elementary schools, communicating to people about the atomic bombing and war from a child’s perspective.

Click here to view the video

In any day and age, war is most miserable for children. They suffer the torment of losing their parents for the rest of their lives. They have nowhere to go and are miserable. I wonder how the children of Ukraine view adults.

Before the atomic bombing, I lived with my parents and younger brother in the area of Kusunoki-cho, 1-chome (now part of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward), located 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. I was in the second grade at Misasa National School (present-day Misasa Elementary School), when I experienced the atomic bombing at a shrine in the area. I ran to a river close by and found a boat carrying the wounded with my father among them. He was covered in blood after experiencing the bombing while working at a nearby factory. I soaked my clothes in water and repeatedly wiped off his body. I still remember him calling out to me, “Takeshi...,” in a faint voice I could barely hear.

Carrying so many people, the boat ultimately capsized. My father and I held on to a board as black rain fell around us, but before I knew it, he had disappeared. “Dad,” I called, shouting myself hoarse. If my father had called out my name, I would have tried to save him and also drowned. Remaining silent was the last sacrifice that my father made for me, but losing him that way was gut-wrenching.

The next day, children who had been orphaned by the bombing were placed on a truck and sent to a farm on the outskirts of the city. I stayed there for a few days but slipped out of the house in the middle of the night because I wanted to see what had happened of my mother and two-year-old brother. I found their remains where our house had been before the bombing. I had witnessed so many dead bodies already that I felt no emotion upon finding them.

I was placed in the care of ordinary families and a police station, but I longed to see my immediate family. I went to my grandmother’s place in the town of Suo-oshima, in Yamaguchi Prefecture, receiving money and food from people I didn’t know. There were no A-bomb survivors around me, and I was bullied at school. My classmates would warn me to not come too close because they didn’t want to be “infected by the A-bomb.” It was terribly frustrating. I always have had worries about my health and was diagnosed with colon cancer in my 50s.

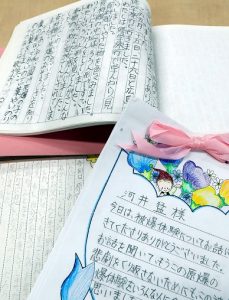

Because I have survived, I came to the conclusion that I had to share my story. Now I communicate my experience in the atomic bombing at elementary schools in Hofu City. Each time, the sincere look in the children’s eyes gives me hope.

On the other hand, news about war is too distressing to watch. Even now, at night, tears come to my eyes when I remember how I lost my father at that time. I hope Russian President Vladimir Putin visits Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (in the city’s centrally located Naka Ward) and learns what nuclear weapons are like. For children, parents can never be replaced. I don’t want anyone to experience losing their parents the way I did. (Interviewed by Minami Yamashita)