Survivors’ Stories: Hirotoshi Morimoto, 90, Naka Ward, Hiroshima City—Most classmates were killed

Mar. 20, 2023

Feelings of survivor’s guilt remain

by Rina Yuasa, Staff Writer

On the morning of August 6, 78 years ago, Hirotoshi Morimoto, then 13, was supposed to be with his classmates in the area where the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and International Conference Center Hiroshima (in the city’s Naka Ward) are now located. Nearly 200 of his classmates died in the atomic bombing, but he survived because his plans for that day had unexpectedly changed. After the war, he continued to have feelings of guilt about the fact that only he had survived.

At the time, Mr. Morimoto was a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Shipbuilding Engineering School (present-day Hiroshima Municipal Commercial High School). Few classes were available to the students due to the war, however, and students were being mobilized to demolish houses to create fire lanes in the area of Zaimoku-cho (now part of Naka Ward).

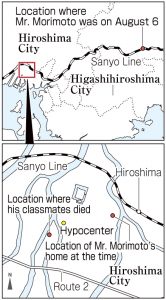

His family was composed of his two parents, himself, and his younger brother. His father had been drafted into the military and was stationed in Yokohama, however, and his brother in the fifth grade of a national school had been evacuated to the area of Saijo-cho (now part of Higashihiroshima City), where he was staying with relatives. In Mr. Morimoto’s home in Nobori-cho (now part of Naka Ward), five relatives, including his uncle and his five-year old son named “Occhan,” were living together with him and his mother, Yoshiko, because the home of the relatives had been designated for demolition, and they were forced to move out. Occhan was considered a happy, active child.

Around that time, Mr. Morimoto and his mother were preparing to evacuate to the village of Nishitakaya (now part of Higashihiroshima City). On the evening of August 5, he and his mother hurriedly transported their belongings to the village using a truck that suddenly they were able to borrow. Although he had never missed his shift of the demolition work before, he decided to take off the next day because he had to stay the night to help with the drying of clothes.

On the morning of August 6, the atomic bomb dropped by the U.S. military exploded about 600 meters in the sky above Hiroshima City. Mr. Morimoto was about 40 kilometers away but recalled how he saw “the world go completely white.” Returning to Hiroshima on August 8, they found that the city had been reduced to smoldering ruins. Their home, about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, was burned to the ground. A skull, believed to be that of the tobacco-loving elderly woman who lived next door, was lying on the ground with a charred tobacco pipe.

As he remained standing at the ruins, his uncle appeared and began to cry while reporting the news that Occhan had become buried under the collapsed house and was overcome by flames from the fires that arose after the bombing. Unable to move a beam that had fallen on top of him, his uncle could only stroke his screaming child’s legs. From that time on, his uncle always hung from his neck an urn containing Occhan’s ashes.

Mr. Morimoto also lost friends. According to the Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, 194 of his classmates and five teachers working at the site, about 500 meters from the hypocenter, were killed instantly. Only Mr. Morimoto and a few others survived. “How they must have suffered with serious burns. I am at a complete loss for words,” Mr. Morimoto said.

The year after the bombing, he fell ill and visited the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (present-day Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital), where he was diagnosed with stomach ulcers and polyps. The physician treating him informed him he was suffering from “A-bomb disease.” He had to undergo two abdominal operations without general anesthesia, moaning in pain, because supplies were in scarce supply in those days. “For the rest of their lives, A-bomb survivors are beset by the fear that they might become sick from the bomb’s radiation,” said Mr. Morimoto. While managing a liquor shop and doing other work, he continues to be conscious of remaining in good health.

Each year on August 6, he participates in his alma mater’s memorial service, feeling guilty and too ashamed to face the bereaved families of his classmates. Even today, he often stops by at a monument at the school in commemoration of those lost that day. He traces the names inscribed on the monument, remembering the memories of his school days, such as a tall classmate or a strict teacher. “I’m so sorry I was the only one who survived,” he remarks at the monument.

He has been sharing his A-bomb experience with students at local schools for a few years, but he hesitates to convey all of the details of that day’s horrific event. He worries that such information “might be traumatic for the children.” At the same time, his anxiety grows that “people might repeat the same mistake so long as nuclear weapons exist.” He truly hopes “people learn about the horrors of nuclear weapons from our experience.”

(Originally published on March 20, 2023)