Hiroshima Summit—Recovery after A-bombing, Part 2: Okonomiyaki

Apr. 1, 2023

“Soul food” born of street stalls

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Back in August of 1965, okonomiyaki food stalls — with the names Momotaro, Chii-chan, Henkutsu-ya, and so many others — were packed into the Nishi-Shintenchi Square (now part of Naka Ward), in the central area of Hiroshima. A stall named Rei-chan was one. Inspiration for the name of the stall when her parents started it was Reiko Yamashiro, now 84, a resident of Higashihiroshima City. “Sometimes the girl in the stall next to ours would cook the batter for us, and we would share vegetables. We all got along well,” recalled Ms. Yamashiro fondly.

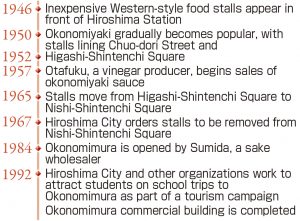

Okonomiyaki is known as the “soul food” of Hiroshima. Its origins are considered to be issen yoshoku (loosely translated as ‘inexpensive Western food’) sold at stalls in the burned-out ruins of the city after the atomic bombing. This simple food evolved into the current okonomiyaki in step with the city’s recovery after the war. Piles of shredded cabbage, slices of pork, noodles, and other ingredients are placed on a mixture of flour and water that has been spread out like a crepe on a heated iron plate. After everything is cooked, a broken cooked egg is added, and the entirety is topped with a thick, sweet sauce.

In the 1950s, the department store Hiroshima Tenmaya opened near the Higashi-Shintenchi Square (in present-day Naka Ward). Movie theaters and restaurants lined the streets, and any trace of the atomic bombing had nearly disappeared. The Rei-chan establishment, now located inside the commercial hub known as Ekie in the JR Hiroshima train station, was opened in Higashi-Shintenchi Square around 1955 by Nobuto Yamashiro, a native of Higashihiroshima City, and his wife, Toshie, as a way to make a living. The restaurant later moved to Nishi-Shintenchi. Nobuto died in 1987 at the age of 71, and Toshie in 2005 at the age of 86.

At first, the stall sold amazake (a sweet drink made from fermented rice or sake lees) and oden (a pot of assorted vegetables, eggs, and meat). Around 1957, they began selling okonomiyaki, which had become popular. The couple cooked okonomiyaki on an iron plate placed over two charcoal briquettes. In the beginning, the ingredients consisted of dried bonito flakes and deep-fried tempura batter balls. Later, noodles were added to satisfy the hunger of customers, ultimately becoming the standard for the dish. Kyoko Okita, 82, Reiko’s younger sister who is a resident of Higashihiroshima City, helped manage the stall. She recalls that the restaurant was “busy until late at night with people coming in after work, taxi drivers, and newspaper staffers.”

Why did okonomiyaki become so popular in Hiroshima in the period after the atomic bombing? Kenichi Hosoi, 55, dean of the faculty of business administration at the Hiroshima University of Economics, is knowledgeable about okonomiyaki’s history. He believes the popularity derived mainly from the fact that wheat flour sent by the United States as an aid supply came into widespread use in a short time. The popularity of okonomiyaki led to the growth of related local industries, such as sauce producers, noodle makers, and iron plate manufacturers. Ms. Okita recalls, “My father advised sauce makers to put more apples and onions in their sauces.”

Unauthorized stalls and noise from the area became such serious problems that, in October 1965, the Hiroshima City government banned the use of Nishi-Shintenchi Square, driving out all the food stalls. Many moved to nearby Okonomimura, a cluster of okonomiyaki restaurants, or the Hiroshima Station building and continued their businesses. Many private homes even in the outlying areas of the city were turned into okonomiyaki shops. With the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, the local professional baseball team, capturing the Central League championship for the first time in 1975 and the city making special efforts to invite students on school trips to Okonomimura, Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki gained quite a following throughout Japan.

Hidenori Kashida, 67, third-generation owner of Rei-chan, said, “I would be pleased if okonomiyaki grew in popularity throughout the world, along with its history of repeated trial and error ever since Hiroshima’s recovery period.” He has high hopes for the summit of the G7 (Group of Seven industrialized nations), scheduled to be held in Hiroshima in May.

Many okonomiyaki restaurants in Hiroshima have names that incorporate the word “chan” (suffix added to someone’s name as a diminutive). One theory says that “chan” was first used by women in the ruins of the city who had lost their husbands in the atomic bombing or the war; another has it that the suffix was used to make it easy for husbands to recognize when they returned home from the war. Such theories might have resulted from efforts by local governments and travel agencies to promote okonomiyaki as a symbol of the city’s reconstruction. In reality, in many cases, the restaurants were named after an owner’s nickname or a daughter’s name, and so on.

At the peak of the food’s popularity, about 2,000 okonomiyaki restaurants were said to have existed in Hiroshima Prefecture. The number has decreased due to the aging of owners and the coronavirus pandemic, with currently only about 1,300 such restaurants in the prefecture. Nevertheless, according to a 2018 survey conducted by Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Hiroshima Prefecture has the highest number of okonomiyaki, yakisoba (stir-fried noodles), and takoyaki (balls of dough with fried octopus) restaurants per 1,000 residents in Japan.

(Originally published on April 1, 2023)