Hiroshima Summit—Recovery after A-bombing, Part 4: Children’s facilities

Apr. 3, 2023

Support bears fruit from teachers and individuals of Japanese ancestry

by Michiko Tanaka, Senior Staff Writer

On May 3, 1948, three years after the atomic bombing, a large facility with an arched roof was erected in the area of Motomachi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), which was still a burned ruins. “It was a time we had nothing, you know, so I was so pleased with the spacious, elegant building,” said Yoshihiro Harada, 86, a physician who is a resident of Naka Ward. At the time, he was a sixth-year student at Honkawa Elementary School. Attending the opening ceremony of Hiroshima Children’s Culture Hall as one of the youth representatives, he was on the receiving end of baseball equipment presented to the A-bombed Hiroshima by Japan’s Crown Prince at the time (present-day Emperor Emeritus Akihito).

Unfortunately, it was raining that day. Mr. Harada appeared, decked out in rain boots, in the May 4th edition, the following day, of a local newspaper. Despite the weather, the hall was overfilled with children. Following the opening ceremony, all the participants enjoyed singing and dancing, “As if intending to drown out the sound of pouring rain” (quoted from the May 4th issue of the Yukan Hiroshima, a local evening newspaper). The social gathering, with children also invited from the families of Occupation forces, was also full of excitement.

It was only natural that children in the A-bombed city were excited. Everyone had suffered physically and mentally from the atomic bombing. In the spring of 1945, Mr. Harada had left his home in what is now Peace Memorial Park (in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), moving to his grandparents’ house on the outskirts of the city. Although with the move he was able to avert the atomic bombing on August 6, he still lost many of his relatives, including grandparents and uncles on his mother’s side of the family. Day after day, people with severe burns lined up to see his grandfather, who was also a physician.

Honkawa Elementary School, which he began attending in 1947, was located only 410 meters from the hypocenter, and about 400 students and staff of the school died in the bombing. The reinforced concrete school building barely managed to avoid collapse, but its window frames were twisted and bent out of shape. According to Mr. Harada, there was no glass left in the windows of his classroom. “Wintertime was so cold we would shiver,” he said.

Amid such conditions, the teachers of Hiroshima City were the ones who initiated the movement to build a children’s culture hall. The prospectus for construction, prepared in August 1947, contains the wording, “Looking at the current situation of children who have lost their joy and happiness, and in consideration of Japan’s future, we are driven by an irresistible love for the children and our country.” A military factory located in present-day Hatsukaichi City was transported to a park site leased from the city. With difficulties in fundraising, however, the project was ultimately transferred to the Hiroshima City government. Despite all that, finishing touches were finally put on the large hall, which was equipped with a film projector and an orchestra box.

Mr. Harada was often taken along to the Children’s Culture Hall by his father, Tomin Harada, who was a true lover of music. His father had established a private medical clinic in the city in November 1946 after being demobilized from his duties as a military physician in Taiwan. His father is well known for his dedication to medical care for A-bomb survivors. Mr. Harada says, “I was able to listen to chanson music and watch ballet performances. The hall gave me opportunities to listen to exceptional music at the most sensitive time in my life.” The Children’s Culture Hall was also used as a communal hall, where school festivals and other school events were held.

In 1952, a children’s library was also built in the Motomachi area. The exterior of the building, which was designed by Kenzo Tange, the same person involved in the creation of the city’s Peace Memorial Park, was made entirely of glass. The construction was supported by large donations from people of Japanese descent living overseas, including groups originally from Hiroshima Prefecture who were living in North America at the time.

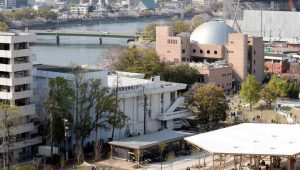

The two children’s facilities were filled with the hopes of many people for the dreams of children in the A-bombed city. Over the years, the Children’s Culture Hall transformed into the Hiroshima City Youth Center, and the Children’s Library became the Hiroshima City Children’s Library. Both facilities continue to be supported and cherished by many members of the public.

*****

One member of the American military supported the children of the A-bombed city both materially and mentally. Howard Bell (1897–1960) was a former staff member of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ). When visiting Hiroshima City’s Honkawa Elementary School in 1947, he was apparently distressed by the plight of the children. He donated a total of 26 dozen lead and colored pencils, as well as 2,500 yen in cash. He later called on the Red Cross Society and churches in his home country to cooperate and expand the circle of support for the children of Hiroshima.

Mr. Bell also had a deep connection with the Children’s Culture Hall. He donated a projector and vinyl records. He delivered a congratulatory speech at the opening ceremony and visited a children’s festival held by the city in 1952. The Hiroshima City Children’s Library holds a large volume of books from overseas, known today as the “Bell Collection,” that arrived courtesy of Mr. Bell in 1949.

(Originally published on April 3, 2023)