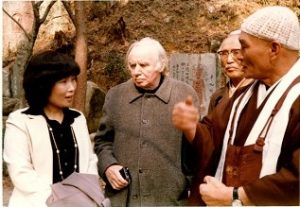

My guidepost, Hiroshima pioneers: Keiko Ogura, 85, A-bomb survivor and interpreter—Robert Jungk, Kaoru Ogura

Jan. 16, 2023

by Hiromi Morita, Kyoko Niiyama, and Rina Yuasa, Staff Writers

There are pioneers in Hiroshima who have revealed the reality of the devastation caused by the atomic bombings and spent lifetimes opposing nuclear weapons and war. The determination of such individuals, who might be called “the original people of Hiroshima,” is still today being passed on to following generations in a variety of ways, not limited to the peace movement. Meanwhile, some of those important journeys are fading into our collective memory as the 78th anniversary of the atomic bombings draws near. In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun asks people who continue to confront the memories of Hiroshima about individuals in the past who served as a “guidepost” in their own lives. We will endeavor here to trace the paths of those pioneers and ensure those stories are committed to memory.

As an interpreter, Keiko Ogura has served as a guide for people coming to Hiroshima from overseas and, in the process, shared her own A-bombing experience with people from all over as an English-speaking survivor of the atomic bombing. At her busiest, she speaks about what happened in Hiroshima to more than 2,000 people each year. “In the past, I always thought I could never step into my husband’s shoes because I had had no connection to his activities. But now I feel a clear connection with him.”

Her husband was Kaoru Ogura (1920-1979), who was born in the United States and had the ability to communicate the reality of the atomic bombings overseas with his linguistic abilities and international mindset. As an official for the Hiroshima City government, Mr. Ogura served in such posts as director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum as well as a guide for international leaders visiting Hiroshima. He worked tirelessly to have A-bombing photography exhibits held at the United Nations headquarters in New York City. With that, he clearly served as a pioneer in spreading the story of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima worldwide.

“At the time of Japan’s defeat in World War II, when Kaoru was a lieutenant in the former Japanese army in Indonesia, I was a second-year student at a national school,” described Ms. Ogura. “Our ages and backgrounds were quite different.” However, Robert Jungk (1913-1994), a Jewish journalist from Germany, played cupid for them. By then, Mr. Jungk was already well known among people for a book he authored detailing the history of development of the atomic bomb.

Ms. Ogura met Mr. Jungk in 1957 for the first time when he was reporting on Hiroshima. Her acquaintance introduced her as “a young female A-bomb survivor who speaks English.” Looking back on that time, Ms. Ogura described how Mr. Jungk’s personal experience of having lost his family in the Holocaust was at the root of his anti-nuclear ideology. “From the bottom of his heart, he despised nuclear weapons for their capacity to take the lives of people’s loved ones without warning.”

Three years later, she happened to meet with Mr. Jungk on another of his visits to Hiroshima. The man standing beside Mr. Jungk at the time was Kaoru Ogura. Kaoru had been assisting Mr. Jungk’s reporting work in Hiroshima in a collaborative role for some time. Her connection with Mr. Jungk naturally led to her contacting Kaoru; they married two years later. She gave birth to their two children and spent busy days raising their children and providing care for her in-laws.

Later, Kaoru collapsed and died while drafting a manuscript for the Peace Declaration, which was to be read by Hiroshima’s mayor on August 6. She was at a loss, with the couple’s children still only 15 and 12. While still in mourning, she received a telephone call from Mr. Jungk, who asked if she would work as an interpreter for him during his next visit to Hiroshima.

She refused his offer at first. “It’s completely beyond me to do interpretation because I have forgotten English,” she had told him. But, he wouldn’t take no for an answer. He finally convinced her, explaining to her that she should communicate the story of Hiroshima to the world, because she knew both the grief of having suddenly lost a loved one and the suffering of A-bomb survivors.

She threw herself into studying English. As a result, she found herself being pressed with work that included interpretation and coordination of journalists and writers coming to Hiroshima from overseas, exactly as her husband had done in the past. Even after Kaoru’s death, a string of people from overseas continued to visit the city to pay their respects to him. Ms. Ogura had the opportunity to meet people who had been good friends with Kaoru and to experience his life vicariously. “Before I knew it, I had been passed the baton for that work.”

In 1983, she attended a mock, anti-nuclear trial held in Nuremburg, located in what was at the time West Germany, on behalf of A-bomb survivors that had become elderly. On the stand, she revealed for the first time her own experience in the atomic bombing at the age of eight. In those days, civic movements protesting the deployment of strategic nuclear arms in Europe had grown in strength. The passion for that work she witnessed before her return to Japan motivated Ms. Ogura to engage enthusiastically in her own activities. In 1984, the following year, she established the volunteer organization Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace (HIP) and, in parallel, founded a company that would provide translation and other services. Since then, she has been on her own career path, based on Mr. Jungk’s words of encouragement.

In recent years, a large volume of Kaoru’s letters to Mr. Jungk over a period of nearly two-and-a-half years, starting in 1957, was discovered. Also found were many documents translated by Kaoru into English, including newspaper articles featuring the situation in Hiroshima, A-bomb survivors’ notes describing their bombing experiences, and interviews. Without that information, Mr. Jungk’s book Brighter than a Thousand Suns might not have been possible.

Ms. Ogura said, “With the recently discovered materials, I was able to reaffirm how deeply Kaoru was involved in Hiroshima, and what he was trying to say.” More than 40 years have passed since she set off on a path in her husband’s footsteps. She now feels that everything in her life to this point has been guided by Mr. Jungk through her late husband, Kaoru.

Profile

Keiko Ogura

Born in Hiroshima City, Keiko Ogura experienced the atomic bombing near her home in the area of Ushita (now part of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward), at the age of eight. Ms. Ogura graduated from Hiroshima Jogakuin University. In 1962, she married Kaoru Ogura. In 1984, she established Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace (HIP), for which she currently serves as director. Since 2011, she has communicated her A-bombing experience through testimonies to the public for the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. Currently, Ms. Ogura lives in the city’s Naka Ward.

Keywords

Brighter than a Thousand Suns

A report written by Robert Jungk about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He focused on the A-bomb victims and argued that humans in the nuclear era were facing an existential crisis. The publication has been translated into more than 10 languages, with the Japanese version published in 1961. Kaoru Ogura helped Mr. Jungk in conducting surveys and providing interpretation and continued to assist Mr. Jungk after his return home. Mr. Ogura was cited in the acknowledgements of the original publication with the words “ideal co-worker.”

(Originally published on January 16, 2023)

There are pioneers in Hiroshima who have revealed the reality of the devastation caused by the atomic bombings and spent lifetimes opposing nuclear weapons and war. The determination of such individuals, who might be called “the original people of Hiroshima,” is still today being passed on to following generations in a variety of ways, not limited to the peace movement. Meanwhile, some of those important journeys are fading into our collective memory as the 78th anniversary of the atomic bombings draws near. In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun asks people who continue to confront the memories of Hiroshima about individuals in the past who served as a “guidepost” in their own lives. We will endeavor here to trace the paths of those pioneers and ensure those stories are committed to memory.

Guided by the two, she communicates message of peace to world

As an interpreter, Keiko Ogura has served as a guide for people coming to Hiroshima from overseas and, in the process, shared her own A-bombing experience with people from all over as an English-speaking survivor of the atomic bombing. At her busiest, she speaks about what happened in Hiroshima to more than 2,000 people each year. “In the past, I always thought I could never step into my husband’s shoes because I had had no connection to his activities. But now I feel a clear connection with him.”

Her husband was Kaoru Ogura (1920-1979), who was born in the United States and had the ability to communicate the reality of the atomic bombings overseas with his linguistic abilities and international mindset. As an official for the Hiroshima City government, Mr. Ogura served in such posts as director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum as well as a guide for international leaders visiting Hiroshima. He worked tirelessly to have A-bombing photography exhibits held at the United Nations headquarters in New York City. With that, he clearly served as a pioneer in spreading the story of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima worldwide.

“At the time of Japan’s defeat in World War II, when Kaoru was a lieutenant in the former Japanese army in Indonesia, I was a second-year student at a national school,” described Ms. Ogura. “Our ages and backgrounds were quite different.” However, Robert Jungk (1913-1994), a Jewish journalist from Germany, played cupid for them. By then, Mr. Jungk was already well known among people for a book he authored detailing the history of development of the atomic bomb.

Ms. Ogura met Mr. Jungk in 1957 for the first time when he was reporting on Hiroshima. Her acquaintance introduced her as “a young female A-bomb survivor who speaks English.” Looking back on that time, Ms. Ogura described how Mr. Jungk’s personal experience of having lost his family in the Holocaust was at the root of his anti-nuclear ideology. “From the bottom of his heart, he despised nuclear weapons for their capacity to take the lives of people’s loved ones without warning.”

Three years later, she happened to meet with Mr. Jungk on another of his visits to Hiroshima. The man standing beside Mr. Jungk at the time was Kaoru Ogura. Kaoru had been assisting Mr. Jungk’s reporting work in Hiroshima in a collaborative role for some time. Her connection with Mr. Jungk naturally led to her contacting Kaoru; they married two years later. She gave birth to their two children and spent busy days raising their children and providing care for her in-laws.

Later, Kaoru collapsed and died while drafting a manuscript for the Peace Declaration, which was to be read by Hiroshima’s mayor on August 6. She was at a loss, with the couple’s children still only 15 and 12. While still in mourning, she received a telephone call from Mr. Jungk, who asked if she would work as an interpreter for him during his next visit to Hiroshima.

She refused his offer at first. “It’s completely beyond me to do interpretation because I have forgotten English,” she had told him. But, he wouldn’t take no for an answer. He finally convinced her, explaining to her that she should communicate the story of Hiroshima to the world, because she knew both the grief of having suddenly lost a loved one and the suffering of A-bomb survivors.

She threw herself into studying English. As a result, she found herself being pressed with work that included interpretation and coordination of journalists and writers coming to Hiroshima from overseas, exactly as her husband had done in the past. Even after Kaoru’s death, a string of people from overseas continued to visit the city to pay their respects to him. Ms. Ogura had the opportunity to meet people who had been good friends with Kaoru and to experience his life vicariously. “Before I knew it, I had been passed the baton for that work.”

In 1983, she attended a mock, anti-nuclear trial held in Nuremburg, located in what was at the time West Germany, on behalf of A-bomb survivors that had become elderly. On the stand, she revealed for the first time her own experience in the atomic bombing at the age of eight. In those days, civic movements protesting the deployment of strategic nuclear arms in Europe had grown in strength. The passion for that work she witnessed before her return to Japan motivated Ms. Ogura to engage enthusiastically in her own activities. In 1984, the following year, she established the volunteer organization Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace (HIP) and, in parallel, founded a company that would provide translation and other services. Since then, she has been on her own career path, based on Mr. Jungk’s words of encouragement.

In recent years, a large volume of Kaoru’s letters to Mr. Jungk over a period of nearly two-and-a-half years, starting in 1957, was discovered. Also found were many documents translated by Kaoru into English, including newspaper articles featuring the situation in Hiroshima, A-bomb survivors’ notes describing their bombing experiences, and interviews. Without that information, Mr. Jungk’s book Brighter than a Thousand Suns might not have been possible.

Ms. Ogura said, “With the recently discovered materials, I was able to reaffirm how deeply Kaoru was involved in Hiroshima, and what he was trying to say.” More than 40 years have passed since she set off on a path in her husband’s footsteps. She now feels that everything in her life to this point has been guided by Mr. Jungk through her late husband, Kaoru.

Profile

Keiko Ogura

Born in Hiroshima City, Keiko Ogura experienced the atomic bombing near her home in the area of Ushita (now part of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward), at the age of eight. Ms. Ogura graduated from Hiroshima Jogakuin University. In 1962, she married Kaoru Ogura. In 1984, she established Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace (HIP), for which she currently serves as director. Since 2011, she has communicated her A-bombing experience through testimonies to the public for the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. Currently, Ms. Ogura lives in the city’s Naka Ward.

Keywords

Brighter than a Thousand Suns

A report written by Robert Jungk about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He focused on the A-bomb victims and argued that humans in the nuclear era were facing an existential crisis. The publication has been translated into more than 10 languages, with the Japanese version published in 1961. Kaoru Ogura helped Mr. Jungk in conducting surveys and providing interpretation and continued to assist Mr. Jungk after his return home. Mr. Ogura was cited in the acknowledgements of the original publication with the words “ideal co-worker.”

(Originally published on January 16, 2023)