Survivors’ Stories: Keisaburo Toyonaga, 87, Aki Ward, Hiroshima City―Mother was lying with her face black and swollen

Apr. 10, 2023

Communicating his A-bombing experience for 40 years, saying, “Please take a baton of peace.”

by Kyoko Niiyama, Staff Writer

Keisaburo Toyonaga began to communicate his experience with the atomic bombing to others and has spoken to many students on school trips to Hiroshima, while working as a high school teacher. He has had two cancers and has continued his talks with interruptions for about 40 years. He calls on children to take a baton of peace from him.

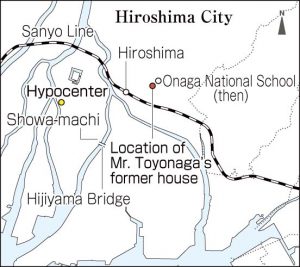

His father died of an illness at the age of 41, and he lived with his mother, Tsuyako, and his brother, Hiroyuki, in Onaga-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward) near Hiroshima Station. In the spring of 1945, the wartime government policy of “evacuation of schoolchildren,” in which children were moved to rural areas in preparation for bombing, began in Hiroshima as well. Mr. Toyonaga, who was nine years old and a third-year student at Onaga National School (Now Onaga Elementary School), was evacuated to his paternal grandparents’ house in Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima prefecture, but he soon returned home because he felt so lonely.

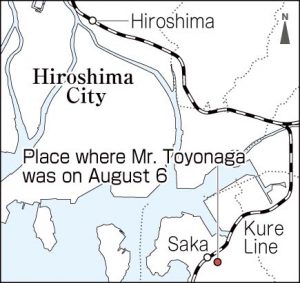

On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was absent from school to receive treatment for otitis media and went alone from his house to an acupuncture and moxibustion clinic in Saka-cho. It was shortly after eight o’clock in the morning when he arrived at Saka Station (now part of Saka-cho) on the Kure Line by train. As he was walking, he heard a roar from behind. He quickly ran under the nearby eaves. He saw a mushroom cloud rising in the sky in the direction of the city of Hiroshima.

As a neighborhood association activity, his mother and then three-year-old brother had gone to Showa-machi (now part of Naka Ward) on the west side of Hijiyama Bridge to demolish buildings to create fire lanes so the spread of fire could be avoided in case of air strikes. He became worried and tried to return to the city of Hiroshima from Saka Station, but no train came. When the train finally arrived, he was surprised to see people who came out of the train. He said, “Their skin hung down from their limbs and their hair stood on end, making them indistinguishable from men to women.”

His return train stopped at Kaitaichi Station. Mr. Toyonaga set out for his house on foot. In the direction of the city center, the sky turned red with fire. He was evacuated to his relative’s house in Funakoshi-cho (now part of Aki Ward), and the next day, began searching for his mother and brother with his grandfather and cousins.

His house, which was located about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, was totally destroyed by fire. Three days after the A-bombing, he was able to meet his family again at Mt. Futaba. His mother was lying on the ground with serious burns. Her face was black and swollen, and her kimono was in tatters. He said, “If my brother, who was unharmed, had not been by her, I could not have recognized her as my mother.” Thanks to her relatives’ great care, she gradually recovered and settled in Funakoshi-cho after the war.

Mr. Toyonaga became a teacher at a private high school after graduating from Hiroshima University. In 1983, at the request of a teaching acquaintance, he spoke for the first time about his A-bombing experience to high school students from Osaka who were visiting Hiroshima on a school trip. At this time, he asked his friends of A-bomb survivors for their cooperation, and 15 people gathered.

As he was about to leave, he was encouraged by a student who said to him, “Please continue to talk to many children,” and the following year he formed the “Hiroshima o Kataru Kai,” a group that shared their experiences of the A-bombing in Hiroshima, with 13 people who had communicated their A-bombing experiences with him. Though it was disbanded in 2001 due to the aging of its members, Mr. Toyonaga himself continues to communicate his experience.

He has also been working for many years to support A-bomb survivors living abroad. Many people who came to Hiroshima from the Korean Peninsula, which was colonized by Japan, in poverty or forced to work, were exposed to the A-bombing. Even after returning home after the war, they suffered from illness or poverty, but for a long time, the Japanese and South Korean governments virtually neglected them. Mr. Toyonaga formed a support group and appealed for aid together with Korean A-bomb survivors. He said, “A-bomb survivors are A-bomb survivors, no matter where they are. I wanted to support people whose existence had been forgotten.”

Fellow A-bomb survivors die every year due to old age or illness. He puts even more efforts into activities that convey his experience to many children. He hopes that those who listen to him will become his successors and expand the circle.

(Originally published on April 10, 2023)