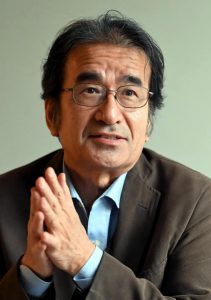

My guidepost, Hiroshima pioneers: Motoo Nakagawa, 64, citizens group representative—Genkichi Tahara and Toshiko Saiki, communicated victims’ regrets

Feb. 20, 2023

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

Motoo Nakagawa works as a representative of the citizens group Hiroshima Fieldwork Executive Committee while continuing his work as a high school teacher. The group’s motto is “Remembering, recording, and sharing.” Each morning since 2016, he has posted what is called “Pika Goyomi” (in English, ‘A-bomb calendar,’ listing the number of days since the atomic bombing) on social media. That was the time he took on the aspiration of a mentor who had made that his life’s work to ensure the suffering and anger of the atomic bombing victims would not be forgotten over time.

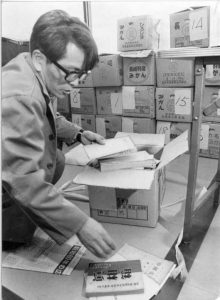

The mentor was Genkichi Tahara (real name: Tsukasa Tahara), a researcher with no formal institutional affiliation who put his heart and soul into collecting and analyzing A-bombing information and died in 2017 at the age of 84. In 1968, Mr. Tahara formed the Hiroshima Society for the Research of Atomic Bomb Sufferers together with Toshihiro Kanai, former chief editorial writer of the Chugoku Shimbun, and others. They published four volumes of a comprehensive record of information about the devastation wrought by the atomic bombing, covering all related literature and notes, over the course of 15 years. Aiming to “restore the rights of those who were forced to die tragic deaths,” he established the Pika Shiryo Kenkyusho (‘A-bomb materials research center’) by himself and continued to call out the absurdity of the atomic bombing.

The Pika Goyomi calendar was part of such activities. He began distributing leaflets and placing advertisements in newspapers at his own expense in the 1960s to warn people to never forget the tragedy of the atomic bombing. Mr. Nakagawa explained, “For Mr. Tahara, every second of his life seemed to involve the atomic bombing.”

Mr. Nakagawa met Mr. Tahara in the mid-1980s. He was invited to Mr. Tahara’s study meetings and began to help compiling materials, observing up close how Mr. Tahara devoted his energies to working on information related to the A-bombing. Mr. Tahara was reticent about himself, but the experience of losing his younger brother on the way back to Japan from the Korean Peninsula after the country’s defeat in the war and of witnessing wounded A-bomb survivors served as the impetus for his work.

Mr. Tahara would not permit Hiroshima’s tragedy to be described with ambiguity and taught the importance of always consulting primary materials. “He often told me that the dead cannot speak and only their deep-seated malice remains. That is precisely why he maintained a strong will to gather facts, making sure that exaggerations and untruths were not be passed on to future generations,” Mr. Nakagawa said. After the death of Mr. Tahara, Mr. Nakagawa recalls his persistence when organizing the huge volume of materials he left behind.

One day, Mr. Tahara said to Mr. Nakagawa he would introduce him to the female version of himself. That woman was Toshiko Saiki, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. She worked every day for more than 40 years cleaning the area around the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, a structure in Peace Memorial Park that contains the remains of unidentified or unclaimed victims, listening to the voices of regret of the victims. She searched for the bereaved families of the victims stored in the mound and spoke with young people about her own A-bomb experience and family members killed in the bombing. “The tragedy that occurred in Hiroshima is ageless,” she would say.

Mr. Nakagawa began to stop by the memorial mound after work to speak with Ms. Saiki, even inviting her to his high school to share her A-bombing experience with students.

Mr. Nakagawa initiated the Hiroshima Fieldwork group in 1994 in the hopes of having as many people as possible listen to Ms. Saiki’s story. Participants would walk through the park, which was a city neighborhood before the atomic bombing, and listen to Ms. Saiki’s testimony at the memorial mound. After Ms. Saiki fell ill in 1998, former residents of the vanished neighborhood joined in the activity and learned of the actual lives of the people at that time through simple topics, such as how they ate soybeans in those days, as well as of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

That is one of the things Mr. Nakagawa learned from the two mentors. “Mr. Tahara taught me that a single flyer can be more important than an elaborate publication. Most people in the city would not immediately call for nuclear abolition based on their own experiences. I want to gather and pass on seemingly insignificant voices and facts.” Mr. Nakagawa said he will also continue to compile booklets of records of information related to the bombing.

More than five years have passed since his mentors died. He sometimes wonders how many people in Hiroshima remember them now. He said he will remember, record, and share the fact that there were indeed special people worthy of remembrance.

Profile

Motoo Nakagawa

Born in Otake City, Mr. Nakagawa graduated from Hiroshima University. Afterward, he became a prefectural high school teacher. He met Genkichi Tahara and Toshiko Saiki in the mid-1980s, deepening his friendship with them over time. In 1994, he formed the Hiroshima Fieldwork Executive Committee and has been a representative of the group ever since. He currently lives in Hiroshima City’s Minami Ward.

Keywords

Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound contains the unclaimed remains of unidentified victims and entire families wiped out in the atomic bombing. After the bombing, countless bodies were brought to the area, close to the hypocenter, and cremated. A temporary memorial with a vault and a chapel built in 1946 was replaced in 1955 by the present-day Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, which has an underground vault where remains are stored. The mound was once known as Genbaku Nokotsu Anchisho (‘Resting place for the remains of A-bomb victims’), a name that Toshiko Saiki insisted on using.

(Originally published on February 20, 2023)

Motoo Nakagawa works as a representative of the citizens group Hiroshima Fieldwork Executive Committee while continuing his work as a high school teacher. The group’s motto is “Remembering, recording, and sharing.” Each morning since 2016, he has posted what is called “Pika Goyomi” (in English, ‘A-bomb calendar,’ listing the number of days since the atomic bombing) on social media. That was the time he took on the aspiration of a mentor who had made that his life’s work to ensure the suffering and anger of the atomic bombing victims would not be forgotten over time.

The mentor was Genkichi Tahara (real name: Tsukasa Tahara), a researcher with no formal institutional affiliation who put his heart and soul into collecting and analyzing A-bombing information and died in 2017 at the age of 84. In 1968, Mr. Tahara formed the Hiroshima Society for the Research of Atomic Bomb Sufferers together with Toshihiro Kanai, former chief editorial writer of the Chugoku Shimbun, and others. They published four volumes of a comprehensive record of information about the devastation wrought by the atomic bombing, covering all related literature and notes, over the course of 15 years. Aiming to “restore the rights of those who were forced to die tragic deaths,” he established the Pika Shiryo Kenkyusho (‘A-bomb materials research center’) by himself and continued to call out the absurdity of the atomic bombing.

The Pika Goyomi calendar was part of such activities. He began distributing leaflets and placing advertisements in newspapers at his own expense in the 1960s to warn people to never forget the tragedy of the atomic bombing. Mr. Nakagawa explained, “For Mr. Tahara, every second of his life seemed to involve the atomic bombing.”

Mr. Nakagawa met Mr. Tahara in the mid-1980s. He was invited to Mr. Tahara’s study meetings and began to help compiling materials, observing up close how Mr. Tahara devoted his energies to working on information related to the A-bombing. Mr. Tahara was reticent about himself, but the experience of losing his younger brother on the way back to Japan from the Korean Peninsula after the country’s defeat in the war and of witnessing wounded A-bomb survivors served as the impetus for his work.

Mr. Tahara would not permit Hiroshima’s tragedy to be described with ambiguity and taught the importance of always consulting primary materials. “He often told me that the dead cannot speak and only their deep-seated malice remains. That is precisely why he maintained a strong will to gather facts, making sure that exaggerations and untruths were not be passed on to future generations,” Mr. Nakagawa said. After the death of Mr. Tahara, Mr. Nakagawa recalls his persistence when organizing the huge volume of materials he left behind.

One day, Mr. Tahara said to Mr. Nakagawa he would introduce him to the female version of himself. That woman was Toshiko Saiki, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. She worked every day for more than 40 years cleaning the area around the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, a structure in Peace Memorial Park that contains the remains of unidentified or unclaimed victims, listening to the voices of regret of the victims. She searched for the bereaved families of the victims stored in the mound and spoke with young people about her own A-bomb experience and family members killed in the bombing. “The tragedy that occurred in Hiroshima is ageless,” she would say.

Mr. Nakagawa began to stop by the memorial mound after work to speak with Ms. Saiki, even inviting her to his high school to share her A-bombing experience with students.

Mr. Nakagawa initiated the Hiroshima Fieldwork group in 1994 in the hopes of having as many people as possible listen to Ms. Saiki’s story. Participants would walk through the park, which was a city neighborhood before the atomic bombing, and listen to Ms. Saiki’s testimony at the memorial mound. After Ms. Saiki fell ill in 1998, former residents of the vanished neighborhood joined in the activity and learned of the actual lives of the people at that time through simple topics, such as how they ate soybeans in those days, as well as of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

That is one of the things Mr. Nakagawa learned from the two mentors. “Mr. Tahara taught me that a single flyer can be more important than an elaborate publication. Most people in the city would not immediately call for nuclear abolition based on their own experiences. I want to gather and pass on seemingly insignificant voices and facts.” Mr. Nakagawa said he will also continue to compile booklets of records of information related to the bombing.

More than five years have passed since his mentors died. He sometimes wonders how many people in Hiroshima remember them now. He said he will remember, record, and share the fact that there were indeed special people worthy of remembrance.

Profile

Motoo Nakagawa

Born in Otake City, Mr. Nakagawa graduated from Hiroshima University. Afterward, he became a prefectural high school teacher. He met Genkichi Tahara and Toshiko Saiki in the mid-1980s, deepening his friendship with them over time. In 1994, he formed the Hiroshima Fieldwork Executive Committee and has been a representative of the group ever since. He currently lives in Hiroshima City’s Minami Ward.

Keywords

Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound contains the unclaimed remains of unidentified victims and entire families wiped out in the atomic bombing. After the bombing, countless bodies were brought to the area, close to the hypocenter, and cremated. A temporary memorial with a vault and a chapel built in 1946 was replaced in 1955 by the present-day Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, which has an underground vault where remains are stored. The mound was once known as Genbaku Nokotsu Anchisho (‘Resting place for the remains of A-bomb victims’), a name that Toshiko Saiki insisted on using.

(Originally published on February 20, 2023)