Hiroshima Summit—Starting point for abolition of nuclear weapons, Part 5: Survivors of exposure to ‘black rain’

Feb. 15, 2023

No “answers” to questions about widespread damage

by Fumiyasu Miyano, Staff Writer

In the mountain valley of the area of Yuki-cho, located in Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward, Masaaki Takano, 84, a local resident, stopped near the road he would walk to and from school and pointed in the direction of the city center. “Clouds arose from that valley and darkened the sky, with burned bits of paper flying on the air. After that, ‘black rain’ started to fall,” he said. The Yuki-cho area is located about 20 kilometers to the northwest of Hiroshima’s A-bomb hypocenter.

He was a first grader at the Sugasawa Branch of the Kamiminochi National School elementary school. During a morning meeting in the classroom, there was an intense flash of light and the sounds of an explosion. Students were sent home, and Mr. Takano was caught in rain on his way home. After the atomic bomb exploded, an ascending air current was generated and black rain containing radioactive particles and soot fell over a wide area. That is the understanding today, but back then, local residents had no way of knowing what was happening.

Diarrhea and fever

After the rain, Mr. Takano drank water drawn into their house from the valley and ate vegetables grown in their field. “There is no doubt I was internally exposed to radiation by ingesting radioactive particles into my body,” he said. He also explained that he experienced diarrhea and had a fever for several days after the rainfall. He now suffers from cancer and kidney disease.

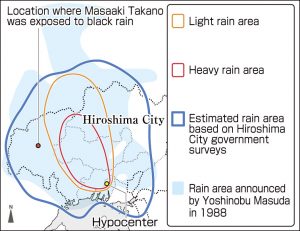

For many years, however, the government provided relief only to those who were exposed to the rain in a 19-kilometer-long, 11-kilometer-wide oval zone designated as the “heavy rainfall area” among the entire region that had experienced some rain after the bombing. In 2015, 84 plaintiffs from Hiroshima Prefecture filed a lawsuit demanding that even those caught in the rain outside the heavy rain area be eligible to receive an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. In July 2021, the plaintiffs won their case in the Hiroshima High Court, and in April 2022, the government introduced new guidelines designed to recognize as A-bomb survivors those whose exposure to black rain cannot be denied and who suffer from among 11 specific diseases.

By the end of January 2023, the prefectural and city governments had issued certificates to a total of 3,281 people. “The truth of black rain has been recognized,” said Mr. Takano. The high court ruling also called into question the government’s “underestimation” of damage caused by the atomic bombing, pointing out the possibility of health damage caused by internal radiation exposure, which the government has consistently denied in court.

Much is still unknown about internal radiation exposure from the ingestion of radioactive particles. Opinions are divided among scientists that have conducted such research in the A-bombed cities. In recent years, however, a series of research findings have shown the possibility of harm caused by internal exposure.

Megu Otaki, professor emeritus at Hiroshima University, published his own epidemiological research findings in 2016. He analyzed the risk of death from solid cancer among people exposed to radiation within two kilometers of the hypocenter and found that the risk tended to be higher for those exposed to radiation on the west side of the hypocenter than for those who were on the east side. That result can be partly explained by radioactive particles being carried by the wind to the west.

Progress in research desired

If internal exposure were to cause effects, it would be because the radioactive particles damage internal organs in the body. Kazuko Shichijo, an assistant professor at Nagasaki University, established in a paper published in 2020 that cells were damaged in the lungs of lab rats that had inhaled radioactive particles, resulting in cellular dysfunction.

On the other hand, the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, an organization jointly managed by the governments of Japan and the United States that is located in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward, has conducted large-scale, long-term epidemiological studies of A-bomb survivors. The organization’s view on residual radiation from black rain and other sources is that, “Its effects are so small that they are negligible when considering the health risks to the A-bomb survivors in general.”

There are no detailed “answers” to questions about the effects of black rain. A 1988 study by Yoshinobu Masuda, former laboratory chief at the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute, showed that the rain fell in areas as far as Hiroshima Prefecture’s border with Shimane Prefecture. Mr. Takano said, “They must face up to the actual situation about the atomic bombing,” expressing his hopes that the damage caused by the atomic bombings will come to be known both inside and outside of the country through the summit meeting of the G7 (Group of Seven industrialized nations) to be held in May in Hiroshima and that research aimed at clarifying the damage will continue to move ahead.

(Originally published on February 15, 2023)