Hiroshima Summit—Starting point for abolition of nuclear weapons, Part 4: Collapse of medical system

Feb. 14, 2023

Student nurse faced with shambles

by Fumiyasu Miyano, Staff Writer, and Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

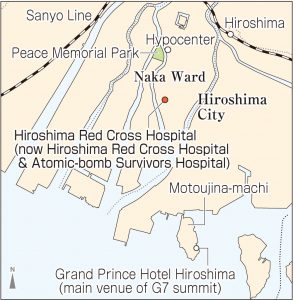

A memorial monument made up of window frames forlornly bent by the A-bomb’s blast from one section of a wall of the old Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (present-day Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital, in the city’s Naka Ward), which was located about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, stands near the hospital’s current location. Nobuko Hayashi, 95, a former medical nurse who now lives in the city’s Saeki Ward, stood in front of a cenotaph next to the monument with the help of a cane, repeatedly touching the names of her acquaintances inscribed there.

“One classmate died when her face was crushed by a pillar. I worked desperately, thinking that I had to do it all myself,” she said as she traced her memories of that day 78 years ago, when she persisted in caring for the wounded after the atomic bombing. Her white uniform had been turned red with blood from wounds to her own body.

At the time, she was in the second year of a nursing program at the Japan Red Cross Hiroshima Branch Hospital, taking a major role in filling in for the nurses who had been sent to battlefields in the war. August 6, 1945, was the morning after she had pulled night duty. As she was washing gauze in the hospital, she felt an intense light, and some kind of flying object hit her directly in the head. She lost consciousness for a time. The wooden dormitory next to the hospital where her classmates lived had collapsed and later went up in flames.

Running short of medical supplies

“As soon as I understood that Hiroshima had been attacked, I knew I had to check on my patients to see if they were all right,” Ms. Hayashi recalled. Avoiding broken objects scattered about the hospital, she evacuated the patients to the basement. There was hardly anywhere to stand in the lobby because the numbers of wounded overwhelmed the hospital, which was built of reinforced concrete and survived the fires that arose immediately after the bombing. Some grabbed her at the ankles asking for help and others requested water. “It was a shambles,” Ms. Hayashi recalled of the scene in a trembling voice.

With hospital medical supplies running short, hospital staff were unable to do so much as clean out the wounds of patients. Still, she looked after the wounded to the extent possible, picking out maggots from their backs and applying Mercurochrome or zinc oxide to wounds. Many suffered severe injuries that appeared irreparable and died the next morning. Cremation of corpses took place next to the hospital nearly every day, but she could not even afford the emotion to feel pity.

Her health also deteriorated

It was not until about two months later that she could take time off and return to her parents’ home in Miyoshi City. She was confined to bed for days with a fever and bleeding from the gums. Although diagnosed with pneumonia, she believes that was also the result of her experience in the atomic bombing, since her symptoms were consistent with the acute symptoms that arise following exposure to high doses of radiation.

Other hospitals were also severely damaged in the bombing and 225 physicians were killed, resulting in the collapse of the city’s medical system. People from outside and inside the city involved in the post-bombing rescue efforts were also exposed to radiation, putting their own health at risk. The message communicated by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) involves the impossibility of coming to terms with the catastrophic consequences of the use of nuclear weapons. The organization, which conducts relief operations on battlefields from a neutral perspective, has strengthened its call for a ban to be placed on nuclear weapons, using what happened in the A-bombed cities to bolster its argument.

In response to the appeals made by the ICRC and other organizations, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was enacted in 2017, based on the approval of 122 countries and regions, and entered into force in 2021. However, nuclear weapons states continue to turn their back on the treaty, and Russia, which launched its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, has even hinted at the possible use of nuclear weapons. Ms. Hayashi, who began to testify about her A-bomb experience to the public when she was in her 70s with the hope that nuclear weapons would be abolished, has been deeply distressed to hear the news about the war in Ukraine. “I want the world’s people to understand the suffering of people who experienced the atomic bombings,” she said.

Vehicles carrying the leaders of nations visiting Hiroshima for the summit meeting of the G7 (Group of Seven industrialized nations) might travel on Yoshijima-dori Avenue, close to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital memorial, when traveling between the Grand Prince Hotel Hiroshima, the main venue of the summit in the city’s Minami Ward, and Peace Memorial Park, in Naka Ward. “Humans must come together and renounce war to create a world of peace and justice,” reads the wording inscribed on the memorial, a message that is aligned with Ms. Hayashi’s desire for a world free from nuclear weapons and war.

(Originally published on February 14, 2023)