Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Interview with Eizo Kote, production team member for Mugen–no–Hitomi, film about school friend with leukemia from A-bomb radiation

Mar. 19, 2023

Anger against nuclear weapons reflected in film

With concerns about Russia’s use of such weapons, “Now is the time for people to feel our friend’s distress”

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Ten years after the U.S. military dropped the atomic bomb, the documentary film Mugen–no–Hitomi (in English, ‘Infinite Eyes’)” was produced by the student council of Seijo High School, located in Tokyo. The movie recorded the life of a young high school student who died of leukemia, a disease that had increased sharply among A-bomb survivors during the early days of the citizens’ movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs, and a call by schoolmates who had been moved to action by their classmate’s distress. Amid the situation of increased concern over Russia’s possible use of nuclear weapons in its invasion of Ukraine, the alumni and others of the school who made the film are hoping more people will watch the documentary and give further thought to the need for the elimination of nuclear weapons.

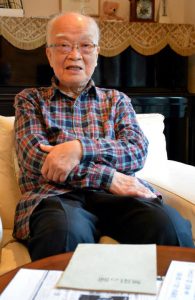

“We wanted to save Mr. Chiba. Our motivation for producing the movie was based on those pure feelings as well as our anger against war and atomic bombs,” said Eizo Kote, 85, a resident of Tokyo who engaged in the film’s creation as secretary of the student council while he was at Seijo High School.

In the fall of 1954, Makoto Chiba, then a third-year student at the school and a year older than Mr. Kote, was hospitalized with myeloid leukemia. Mr. Chiba had experienced the atomic bombing at his family home in the area of Teppo-cho, located in the central area of Hiroshima and now part of the city’s Naka Ward, losing his mother and younger brother. He later moved to Tokyo where his father had been transferred for work. Story has it that he was a shy student who liked playing softball.

In March of the same year, the tuna fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru (‘Lucky Dragon No. 5’) was exposed to radiation in what were called the “ashes of death” resulting from a U.S. military hydrogen bomb test. Subsequently, a signature-collection drive calling for a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs spread across Japan. Mr. Kote said, “Fear of atomic and hydrogen weaponry, about which we had just started to become aware, grew into an immediate threat given Mr. Chiba’s status.” In those days, the national government did not provide assistance to A-bomb survivors. With that, the student council began to collect donations to cover the necessary expenses for blood transfusions used in Mr. Chiba’s treatments.

Circle of support enlarged

Numerous other schools inside and outside of Tokyo joined the campaign, as those schools were members of the same Junior Red Cross as the student council of Seijo High School. A student from Waseda University, located near the school, recommended that the student council members produce a documentary with the aim of further expanding the circle of support for Mr. Chiba. When the student council members informed Mr. Chiba of their plans to make a documentary, he expressed his pleasure. “I look forward to it,” he said.

The film’s scenario was written by the late Tadayoshi Kudo, president of the student council at that time. Someone in the film industry offered support and provided advice on the film’s production. The student council members began filming in March 1955, recording scenes of Mr. Chiba in his hospital bed as well as recreated scenes in which students and teachers played roles depicting how the donation campaign was carried out.

The title of the movie was derived from a sentence contained in a collection of student writings made and sent to Mr. Chiba by Minoshima High School in Wakayama Prefecture that read, “Infinite eyes throughout Japan have been watching you with hopes for your full recovery.” Mr. Chiba persisted in his fight against the disease, saying, “I’ll be well by the time the weather turns warm. And I’ll work hard to return your kindness.” Nevertheless, he died on May 3, 1955.

“With Mr. Chiba’s death, we were struck by a sense of failure because we were unable to save him,” said Mr. Kote. However, the students continued making the film, shooting images of the funeral that had been organized by the school and completing production in late May. In the final scene, Mr. Kudo reads out the students’ thoughts in a memorial address. “We are absolutely opposed to the use of atomic or hydrogen bombs, as well as wars in which humans kill each other without remorse,” he said. “We will never forget your passing.”

The movie drove young people in Japan to take action. Junko Nakamura, 84, a resident of Nishinomiya City, Hyogo Prefecture, was then a second-year high school student at Aichi Shukutoku High School, located in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture. Together with classmates, she folded one-thousand paper cranes prior to August 6, 1955, which they then sent to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. Ms. Nakamura said, “We did that because we had become aware of the danger of leukemia that had beset the A-bomb survivors for the first time when we read magazine articles reporting on the Mugen-no-Hitomi.” Sadako Sasaki, the young girl who later became the model for the Children’s Peace Monument, located in Peace Memorial Park, was one of those at the hospital who received the paper cranes folded by Ms. Nakamura. That prompted Ms. Sasaki to fold paper cranes herself, according to a personal note written by the late Kiyo Okura, who stayed in the same hospital room as Ms. Sasaki.

Film posted to pass on memories to young generations

To convey memories of Mr. Chiba to younger people, Seijo High School uploaded the documentary film to YouTube starting in 2020. The film has been donated by the school to the National Film Archive of Japan, in Tokyo. Yoshihiro Nakagawa, 19, a first-year student at Tohoku University who was involved in the initiative to donate the film when he studied at Seijo High School, said, “I watched the movie and its depiction of Mr. Chiba’s death gave me a chance to think more about the terror of nuclear weapons as something relevant to my own life.”

Mr. Kote will donate the film’s screenplay, which he has kept this entire time, to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. He said, “I hope many people watch our film under the current situation in which the risk of nuclear weapons use is on the rise.” He anticipates that the movie will again help communicate across regions and nations the voices of citizens seeking peace.

Keywords

Leukemia in A-bomb survivors

Leukemia is a blood cancer that prevents the generation of normal blood cells due to an increase in abnormal white blood cells in a patient’s body. According to findings from research outsourced by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to specialists in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in fiscal 2013, the increase in leukemia incidence reached a peak among A-bomb survivors around 10 years after the atomic bombing. Incidence of leukemia among survivors was four to five times higher than among those unexposed to A-bomb radiation, and several tens of times higher when only children were taken into consideration. The reason for leukemia’s increase among survivors is thought to be because their DNA was damaged by radiation emitted from the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on March 19, 2023)