The Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage — faith, peace and… trees

Jun. 20, 2023

(Many) Pathways to Peace Series

Nassrine Azimi

Hiroshima — This year marks the 1250th anniversary of the birth of the Japanese Buddhist priest, scholar, calligrapher, poet, translator, urban planner, and all-round renaissance man, Kukai, known posthumously as Kobo Daishi. Many special events are planned across Japan, to honor this beloved founder of the Shingon School, born in 774 in Shikoku.

Shikoku is the smallest and historically least developed of Japan’s four main islands, a place of geologically stunning contrasts, dotted with cone-shaped mountains, deep valleys and an incredibly rich diversity of flora and fauna. Not surprisingly the father of Japanese botany, Tomitaro Makino, was born there, and the Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi made it his home, considering the island’s stones some of the most beautiful in the world.

One of Shikoku’s ancient traditions, the circuitous 1200-kilometer, 88 temple pilgrimage, or henro, connects the ancient spiritual sites visited by Kukai during his own journeys of faith around the Island. The Shikoku henro is still wonderfully alive today; its great strength is its inherent inclusivity and flexibility: it can be covered by anyone, and in any shape and form, on foot but also by bike, motorcycle, car, bus or train. Pilgrims can start from Temple #1 and finish at Temple #88, or else proceed in reverse. The pilgrimage can be segmented by prefecture, or simply by whatever bits and pieces one can manage (each method even has a name!). I realized early on I would probably never have the kind of time or temperament to walk the full circuit in one go (40 to 60 days on foot, depending on pace), so I opted for Kugiri-uchi, the ‘by bits and pieces’ method.

Shikoku’s four modern prefectures —Tokushima, Kochi, Ehime and Kagawa — embody distinct missions in the universe of the pilgrimage: spiritual awakening, ascetic training, enlightenment, and nirvana, respectively — but needless to say, walking the henro does not offer only idyllic beauty. In past decades too much prioritizing of access by automobiles and tour buses has meant that in some parts walking remains a challenge. In my most recent trip to Kagawa I had to walk long stretches on asphalt and traffic-filled roads, and saw too many eyesores of industrial clutter and crumbling edifices. Still, walking through rice fields or over forest paths, moments of grace and beauty abound.

For years Shikoku’s four prefectures have made a united attempt — thus far unsuccessful — to register it on the UNESCO World Heritage Site, similar to the pilgrimage routes of the nearby Kii mountains, or of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Economic, environmental, and even political concerns press on the temples, which must deal with real 21st century problems. But precisely because the Shikoku henro is so rooted in past traditions while remaining fully part of our natural and contemporary world, it can provide insights to some of the dilemmas we face today, individually and as societies. What is it that brings me, and so many other non-Buddhists and foreigners, to this remote island pilgrimage?

I was born into an Iranian Muslim family and educated in Catholic and Jewish schools. Like many people of faith, I am tormented by how religion can be hijacked, distorted and corrupted for political purposes, as it was done by the regime in Iran, which has been strangling citizens in the name of Islam for more than 44 years. Walking the Shikoku henro brings home the true meaning of inclusiveness and tolerance, what could be part of any established religion. It helps me think in a deeper way about how faith, including my own, could become a force for good in the world.

Kobo Daishi continues to be venerated in Japan, and not just by the followers of his own faith. Studying his life one is awed by the genius of a man who, though he passed away not yet 62, could achieve so much in a single lifetime. I admire not just his spiritual and intellectual depths, but also his personal courage and a certain cosmopolitan world view: he surmounted incredible odds for the perilous journey to China in 804, learned Sanskrit, studied with and became the chosen disciple of the great Chinese monk and teacher Huiguo, and brought back to Japan much knowledge, including about the perfections of the Tang capital, Chang-an, which later informed the design and construction of his high-mountain monastery at Koyasan. He was deeply rooted in his own culture yet with a broad and far-reaching world view, truly what the writer Shiba Ryotaro called ‘a universal man’. He certainly deserves a place in the pantheon of historical world figures.

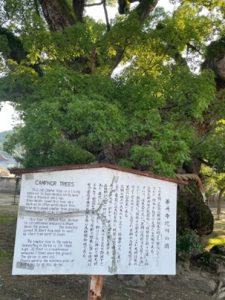

Kobo Daishi’s love for the natural world, too, carries lessons for our own era, when sustainability is sometimes more fashion than ethic. During my latest walk I overnighted at Temple #75, Zentsuji, known to be the actual birthplace of Kukai. In the middle of the vast complex are two giant camphor trees, and a sign indicates that one was beloved by young Kukai himself, making the tree at least 1300 years old. I work with the A-Bombed survivor trees of Hiroshima and have a particular affinity with witness trees, so at dusk I sat a good hour not far from the two ancient camphor, just watching. They appeared so serene, and yet pulsating with life, sustaining the biodiversity of an entire ecosystem. Being in their presence that evening felt like a deep prayer in itself.

With so many problems in the world — from the threats of nuclear weapons, climate change and AI, to the war in Ukraine, human rights abuses in Iran, hardships and fears and poverty for so much of humanity — does walking an ancient pilgrimage of faith help us with our century’s problems? Seeing these magnificent trees was like finding a kind of response, a gift from generations of monks who over centuries protected this temple and its natural treasures. I was awed by the miracle of the trees being alive after more than a millennium, by their breathtaking beauty, the monumental size of their trunks, the visible parts of their vast root systems. I felt the same gratitude I feel when in the presence of the Hibakujumoku of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — and gratitude too for every temple, church, mosque, palace, garden, home — and all who strive to keep ancient trees alive. I felt, once again, that if we can take care of these gentle and generous giants, then maybe we can also learn to take care of the rest, of one another, and of our planet.