Hiroshima Summit—Starting point for abolition of nuclear weapons, Part 3: Victims of “A-bomb disease”

Feb. 12, 2023

Nothing could be done about father’s undiagnosed illness

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

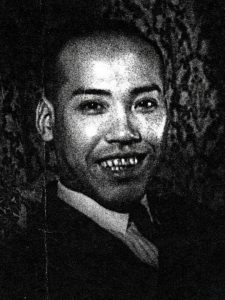

For Yasuyuki Yasuda, 87, an A-bomb survivor who is a resident of Yokohama City in Kanagawa Prefecture, the happenings of August and September 1945 remain deeply etched into his memories of the atomic bombing. He was 10 at the time. After his mother died in the atomic bombing, his family had a chance to rebuild their lives in the ruins of the city, led by his father, Saburo Yasuda, then 41. But on September 12, Saburo passed away at Hiroshima Teishin Hospital, in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward, where he had been hospitalized.

Yasuyuki said, “Despite the burns around his neck, my dad seemed well when he was walking around Hiroshima…” When Saburo died, Chuta Tamagawa, professor at Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School (present-day Hiroshima University School of Medicine) who was investigating the health effects caused by the atomic bombing at Teishin Hospital, performed an autopsy on his father’s body. The autopsy report listed symptoms that were thought to be radiation-induced, such as bruising and hemorrhagic spots on the chest and stomach, as well as hair loss.

Mother died at home in bombing

Before the atomic bombing, Yasuyuki lived in the area of Kaminagarekawa-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward) as a member of a family of five, made up of his parents, himself, a younger brother, and grandmother. His father worked at Fukuya Department Store. Recalling his father, Yasuyuki said, “When I was bullied, he told me he would go and fight the bully. He was a kind father.”

On August 6, Yasuyuki, then a fourth-grade student at a national elementary school, was in the northern region of Hiroshima Prefecture, to where he and other students at school had been evacuated together as a group. Located about 1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter, his home had collapsed and the surrounding area was incinerated by the fires that arose immediately after the bombing. His mother, Toshiko Yasuda, then 31, died while trapped under the family’s house.

On August 17, 11 days after the bombing, Yasuyuki returned to the Hiroshima suburb and reunited with his father, who had also experienced the atomic bombing at home. His younger brother and grandmother were safe. He said, “My younger brother cried as he told me our mother had been burned to death.” Saburo held a can with the mother’s remains and her ring as a memento inside. The next day, his father took Yasuyuki to the ruins around their family home, where they walked around.

After August 20, Saburo began to suffer what he called “unbearable” symptoms. Yasuyuki and others put him on a two-wheeled cart and carried him to Teishin Hospital. When someone mentioned that tomatoes were good for the disease, the son walked in search of tomatoes. But Yasuyuki ultimately had no fix for his father’s mysterious illness. He said, “I was numb when he died.”

A-bomb survivors suffered high fevers and hemorrhaging

The radiation from the atomic bomb caused physical effects in those who had survived the atomic bombing, such as in bone marrow, the organ that produces blood cells. By the end of 1945, many were starting to suffer such acute symptoms as high fevers and blood hemorrhaging. The number of deaths caused by the atomic bombing in Hiroshima from September until the end of December 1945 reached around 9,000 people, the names of whom were confirmed in a survey conducted by Hiroshima City. That reality resulting in criticism that the atomic bomb was inhumane caused the U.S. military, which dropped the bomb, to behave as if it completely rejected the notion.

On September 6, 1945, Thomas Farrell, second in command at the Manhattan Project, the effort to develop an atomic bomb in the United States, released a statement that read, “In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, here at the beginning of September, anyone liable to die has already died and no one is suffering from atomic radiation.” On September 19, the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ), led by the U.S. military, imposed a press code to make media coverage of the atomic bombings subject to its censorship. Restrictions were also imposed on any release of scientific reports based on A-bombing surveys conducted on the Japanese side.

Mr. Tamagawa’s autopsy reports of 19 cases were finally released to the public in a publication titled Collection of Reports on the A-bomb Damage, released in 1953, the year following the official end of the Allied occupation of Japan. Last year, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, in the city’s centrally located Naka Ward, displayed Mr. Tamagawa’s records as part of a special exhibit in an effort to shed light on evidence relating to the inhumanity of nuclear weapons. Yasuyuki agreed to reveal his father’s full name in the exhibit, despite the fact that Saburo’s name had been partially obscured in a previously published collection of reports. Yasuyuki assented based on his wish that nobody should ever have to share his fate.

Yasuyuki survived the post-war period with support from his relatives, got married, and raised two daughters. While he enjoyed a happy family life, his feeling that both war and atomic bombings are unforgivable has only grown, as those acts deprive people of the happiness he has experienced. “Nuclear weapons must never be used.” He hopes that the leaders attending the summit meeting of the G7 (Group of Seven industrialized nations) in Hiroshima can confront and deeply understand the reality of the damage caused by radiation from the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on February 12, 2023)