Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Deaths from leukemia, Part 2: No aid from government

Mar. 21, 2023

Sold land to cover daughter’s medical treatment

In a photograph taken in 1948, three years after the atomic bombing, Hiroko Miyahara, six at the time and wearing a kimono, has the appearance of an older sister. Her cousin Michiko Morita, 76, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, said with a smile as she looked at the photo, “This brings back memories.” She was two at the time of the photo and sat next to Hiroko.

“Hiroko’s house was right next to ours, and she used to play with me when I was a little girl,” she said. “She was healthy, but began to spend more and more time lying around on the floor.” As she continued to talk about Hiroko, Ms. Morita’s voice gradually grew morose.

The increased incidence of leukemia among A-bomb survivors peaked around 1955, with the occurrence growing higher the younger the age was at exposure to radiation from the atomic bombing. Hiroko, who developed the disease later on, was only three years old on the day of the atomic bombing.

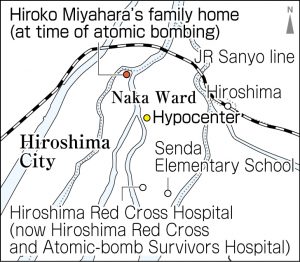

Hiroko’s family managed a futon shop in the area of Tera-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). According to the testimony of her mother, Miyoko Miyahara, which is included in a collection of A-bombing experiences titled Memories of the Flame, Hiroko experienced the bombing while playing at a house next door to theirs, about 1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter. Houses in the area, which was reduced to ashes, were all leveled in the bombing. Hiroko, her mother, and younger brother, who were at home at the time, all survived. Her father, the proprietor of the futon shop, and her grandmother were killed. Ultimately, Hiroko’s mother, Miyoko, died in 2000 at the age of 81.

I want some watermelon

Hiroko’s mother and the two children moved to her parents’ home in the area of Ote-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). The oldest daughter of the mother’s brother, who managed a kimono shop in the neighborhood, is Ms. Morita. “My parents were busy with work at the store, so Hiroko used to take care of me. We would go to a nearby church together every Sunday,” she said.

Hiroko attended nearby Senda Elementary School and is said to have done well at school. Ms. Morita remembers that, around the fall of 1951 when she was nine, Hiroko began to look fatigued and would often lie about on the floor. Her family noticed something was wrong and took Hiroko to a hospital. She was diagnosed with leukemia based on an abnormal increase in white blood-cell count. Hiroko was admitted to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital.

Hiroko’s mother and Ms. Morita’s family took turns staying at Hiroko’s side in her hospital room. Ms. Morita brought a watermelon for Hiroko because she had mentioned she wanted some. When they comforted her by telling her she would be all right, Hiroko expressed her anxiety. “No doctor can cure me,” she explained.

Because her body was unable to produce blood normally, transfusions were a necessity. However, there was as yet no aid available from the national government for A-bomb survivors. A typical starting salary for public servants in those days was around 4,000 to 6,000 yen a month, and the cost of blood transfusions was 2,000 yen a day. After the war, Hiroko’s mother, who earned a living for her family by making futons at home, sold land and other assets to pay for Hiroko’s medical expenses, which amounted to upwards of 300,000 yen.

Leukemia was difficult to treat in those days, unlike today, when drug treatments have been developed. Despite all the care she received, Hiroko died in October 1952 at the age of 10.

Cruel “A-bomb disease”

In its morning edition dated June 7, 1953, the Chugoku Shimbun reported on the issue of leukemia among A-bomb survivors and the cost of treatment, using Hiroko’s case as an example. “This A-bomb disease, which is crueler than poison gas, is known as leukemia in medical science,” reported the newspaper. In 1952, the previous year, the late Takushi Yamawaki, a physician at the Red Cross Hospital, first presented his findings on leukemia incidence among A-bomb survivors at an academic conference, a presentation that attracted considerable interest.

According to Dr. Yamawaki’s personal account, The Atomic Bomb and I, he was urged by the late Fumio Shigeto, director of the hospital, to embark on the research. He repeatedly visited Hiroshima City Hall and extracted leukemia cases from tens of thousands of death certificates. He found that the incidence of leukemia among A-bomb survivors was about four times that of people unexposed to radiation from the bombing, and for those experiencing the bombing less than two kilometers from the hypocenter, the incidence was eight times higher. The study results highlighted the inhumanity of the atomic bombing.

The increase in leukemia, which was proven on the basis of meticulous research conducted by the Hiroshima physician, caused immeasurable loss for many families. Even many years after Hiroko’s death, her mother would mention how Hiroko had been a “good girl.” With memories of playing with her, Ms. Morita continues to visit Hiroko’s grave.

(Originally published on March 21, 2023)