Hiroshima Summit—Recovery after A-bombing, Part 9: Ode to Joy

Apr. 8, 2023

Power of music inspires people

by Masakazu Domen, Senior Staff Writer

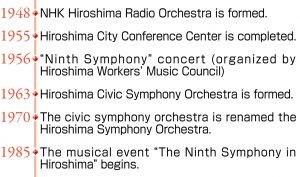

At the end of 1956, a symphonic masterpiece known for its choral fourth movement “Ode to Joy” echoed through the Hiroshima City Conference Center, which had just been built in Peace Memorial Park, in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, the previous year. The entirety of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was played by a mix of local chorus groups and the NHK Hiroshima Radio Orchestra. With four guest soloists, the group performed “All People Will Be Brothers” in German. The sweeping concert comprised four performances held over the two days of December 15 and 16th.

Yorio Takata, 88, a resident of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward, recalled the scene. “The voices of the chorus overlapped with the palpable excitement in the venue. I joined as a member of the hodgepodge of local chorus groups, but I came to understand that this was a place for me as ‘a child of the atomic bombing’.” Mr. Takata sung bass in the chorus that was made up of more than 200 members. He was 21 years old at the time and had just started work as a tax office clerk in the city. “I wonder why I devoted myself to music to that extent, despite being forced to live hand to mouth at the time. Without music, I might have strayed from a righteous life.”

Mr. Takata lost his father, mother, and oldest brother of four siblings in the atomic bombing. He had been evacuated to Shobara City, in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, at the age of 10 with other school children. His father died instantly at his company housing in the area of Teppo-cho, in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward. His mother and oldest brother, who had both been with the father, died within a month of the bombing. Mr. Takata was asked about how he was able to live after the end of the war with an older brother closest in age to him who survived the atomic bombing because he was a mobilized student working outside of Hiroshima that day. “I really can’t remember what we ate to survive,” he replied.

With support from his second oldest brother, who had returned from military service, he was able to attend high school. After he was invited to join the choir club at school, he started to take singing seriously. He continued to sing in a chorus group for workers after graduating from school and participated in the aforementioned 1956 concert.

Isamu Takahashi, 54, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, has kept at his home a record of the concert made up of color photos, which were rare at the time. Mr. Takahashi said, “The photos were left to me by my late father.” His adoptive father, Sadamu Takahashi, who died in 1969 at the age of 62, was the first president of the Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra, which was originally established as the Hiroshima Civic Symphony Orchestra in 1963. While working as a surgeon, Sadamu was also active as a violinist and appeared on stage at the concert.

Mr. Takahashi said, “I think 1956 was around the time when a cultural renaissance was underway in Hiroshima after people’s lives had finally recovered.” The conference center, which was built with donations from the local business community, became a base for such efforts and even served as the venue for the First World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. “My father probably recognized from that performance the power that music had to directly inspire people. That experience might have been the impetus for his idea of establishing the Hiroshima orchestra.”

Another surprising fact is that renowned Japanese singers in those days, such as the soprano Harue Miyake and the tenor Mutsumu Shibata, who were founders of the Tokyo Nikikai Opera Foundation, performed in the concert as guest performers. Their participation demonstrated the strong compassion felt for the A-bombed city. “They were blue-ribbon members. After the concert concluded, Mr. Shibata, one of the great singers of that era, praised us for doing a good job,” recalled Mr. Takata. That event motivated him to continue singing in a chorus and repeatedly participate in “The Ninth Symphony in Hiroshima,” a musical event that began in 1985. “Ode to Joy” represented an ensemble of a variety of thoughts and emotions. The song was nothing if not a note marking recovery of the city.

-End of article

As for the connection between Beethoven and post-war Hiroshima, one well-known legend involves Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony played at Café Musica. In the summer of 1946, the year after the atomic bombing, the late Yoshio Yanagawa opened the Café Musica shop near the Hiroshima train station, with the aim of restoring grace to people’s spirits through music. On New Year’s Eve later that year, when he played a recording of the Ninth Symphony using a gramophone, many people listening to “Ode to Joy” who could not make it into the café are said to have strained to hear the music from outside by pressing their ears against the windowpanes and were apparently moved to tears.

The first regular concert of the Hiroshima Civic Symphony Orchestra, during which three musical pieces of Beethoven were played, was held at the Hiroshima City Conference Center in April 1964. The conference center was rebuilt into the International Conference Center Hiroshima in 1989. Café Musica relocated to another site, before ultimately closing in 2020.

(Originally published on April 8, 2023)