Hiroshima Summit—Recovery after A-bombing, Part 5: Schmoe Houses

Apr. 4, 2023

Goodwill wishes for peace from throughout world

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

As a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima City by the U.S. military, areas within about two kilometers of the hypocenter were burned to the ground, with many citizens losing their homes. Even at the start of the 1950s, there was reportedly a housing shortage of more than 10,000 units. A group of Americans arrived in Hiroshima at that time to engage in the work of building housing on their own initiative with the aim of helping those who had lost their homes.

The mainstay of that effort was Floyd Schmoe, an American forestry researcher and peace activist who died at the age of 105 in 2001. He was deeply distressed by the atomic bombing and planned to raise donations to build what were called “Hiroshima Houses” around the devastated city.

‘The construction was the demonstration of goodwill from hundreds and thousands of people who expressed their remorse about the use of the atomic bomb’ (paraphrased from Mr. Schmoe’s memoir titled Japan Journey). In 1949, carrying glass and nails, he and three friends arrived in Hiroshima from the United States. The group built two row houses in the area of Minami-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward). Between 1950 and 1952, the group also erected 10 houses and a community center in the Eba district (now part of the city’s Naka Ward).

“I jumped for joy when I found a toilet, a bath, and a living room in my house,” said Mieko Kotabe, 84, a resident of Ibaraki City, Osaka. She still remembers the day she visited her new house in the Eba district. In 1950, when she was an elementary school sixth grader, she moved to the house with five other family members—her parents, older and younger sisters, and younger brother.

During the war, Ms. Kotabe lived with her family in the area of Yoshijima-hagoromomachi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). At the time the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the family had been evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, where they rented a farmer’s barn, thus escaping effects from the atomic bombing. Nevertheless, their house in the city was destroyed. In addition, after the war, family members suffered from a series of health problems that prevented them from returning to the city. Later on, her father fell ill and was admitted to a hospital in the city center, where she said the family was introduced to a house by Mr. Schmoe, who was visiting the hospital as part of volunteer activities.

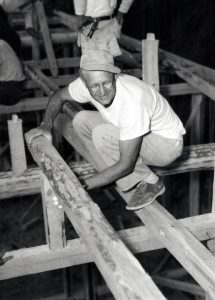

Ms. Kotabe remembers Mr. Schmoe wearing a casual shirt and carrying pillars for new housing he was building in her neighborhood. “I felt that he had a strong sense of conviction and an attitude of getting done what he had decided to get done,” said Ms. Kotabe. Thinking that Mr. Schmoe’s beliefs and name should be remembered, her father would invariably include “Schmoe House” in the return address of his correspondences.

Donations exceeding US$30,000 were collected from throughout the world for the construction of the housing. By 1953, 15 houses with 21 units had been erected in the city. A total of 17 people, including Black and Chinese Americans, participated in the project, with some young Japanese people from Hiroshima and Tokyo also joining in. A sign written in English that stood at construction sites read, “May the building of our home bring us together in mutual understanding and peace.”

The community center in the Eba district, the only structure that still remains among the 15 houses, was renovated and opened as an exhibition facility known as “Schmoe House.” The renovation took place in affiliation with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward, 11 years ago. Members of the citizens’ group Learning from Floyd Schmoe provide guided tours for visitors.

Hiroko Nishimura, 65, director of the group and a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, conveyed something recently said to her by a tourist from Europe — “I’m glad to be here when Ukraine is suffering (due to Russia’s invasion). At a time when division and conflict have escalated around the world, Mr. Schmoe’s desire to promote peace transcending various differences echoes deeply in my heart. I hope that visitors to Hiroshima will take his thoughts back with them to their homes,” said the visitor, according to Ms. Nishimura.

There were other non-Japanese people who were committed to supporting Hiroshima, a city that had suffered tremendous devastation from the atomic bombing. In September 1945, the month after the bombing, the late Dr. Marcel Junod, head of the delegation in Japan of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC, headquartered in Switzerland), delivered about 15 tons of medical supplies to Hiroshima. Dr. Junod also joined in the treatment of A-bomb survivors at relief stations.

In 1949, an American journalist, the late Norman Cousins, proposed the initiation of a “moral adoption movement” for A-bomb orphans. Through that program, American citizens sent childcare expenses and other funds to support the lives of orphans. Monuments to the two aforementioned individuals stand in the green zone at the south end of Peace Memorial Park, in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

(Originally published on April 4, 2023)