Hiroshima Summit—Recovery after A-bombing, Part 7: Motomachi

Apr. 6, 2023

From military base to housing units

by Fumiyasu Miyano, Staff Writer

Michie Tomoda, 83, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, recalled how happy her family felt to move into a wooden public housing unit built in Motomachi three years after the atomic bombing. “The house was clean and comfortable to live in. My mother must have been even happier than I was, given that we had made it back to Hiroshima where we used to live.”

Ms. Tomoda experienced the atomic bombing at her home in the area of Kamiyanagi-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, when she was six years old. Her family fled to the mountain named Ushitayama, where they spent several days. The words “Are we going to die?” uttered by her exhausted mother on the mountain after they had lost their home remain with Ms. Tomoda to this day. After the war, her mother moved the family to present-day Hatsukaichi City in search of a job. However, when a house in the Motomachi area of the city became available, the five-member family returned to Hiroshima, where they had previously lived.

The family’s house was one of a row of connected residences divided into five units. Their unit had two rooms—a six-tatami-mat room and a four-and-a-half-tatami-mat room. The house had a toilet but no bath, which necessitated the family visiting a local public bath for bathing. “I made lots of friends, though,” said Ms. Tomoda, who left Motomachi temporarily after getting married but returned when her child entered elementary school. She still lives in a municipal high-rise apartment complex in the same Motomachi area.

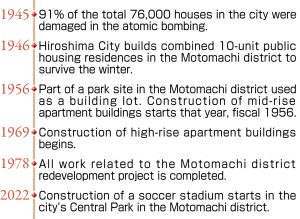

After the Meiji Era (1868–1912), the Motomachi district, an area that surrounds Hiroshima Castle whose etymology suggests it being the ‘birthplace of Hiroshima,’ was the center of Hiroshima as a military city, with numerous military units and facilities. The district, located about one kilometer from the hypocenter, was annihilated in the atomic bombing. In 1946, the city government started building housing as an emergency measure to cope with the shortage of places to live. Alongside a plan in place to use the land for a park, the Hiroshima Prefectural government and other entities joined the housing project, resulting in more than 1,800 public units being built by 1949.

Those who moved into the new public housing units included not only A-bomb survivors who had lost homes in the atomic bombing, like Ms. Tomoda, but also those who had been repatriated after the war. Kazumasa Nakamura, 81, a resident of a municipal mid-rise apartment building in Motomachi, was born in Seoul, South Korea, and came to Hiroshima soon after the war with his five family members, based on help from relatives. In the autumn of 1946, he and his family moved into a combined 10-unit public housing residence. His neighborhood was peopled by A-bomb survivors who suffered from keloid scars as well as day laborers. “A variety of people would gather in the house. They had no money, but they were energetic,” said Mr. Nakamura.

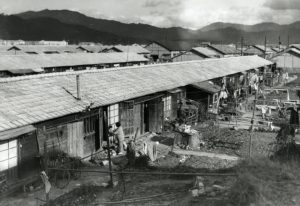

On the other hand, so many people had returned to Hiroshima that those who could not obtain public housing built shacks on the riverbanks and vacant lots across the city. The banks of the Ota River were crowded with those who had lost their homes in the city’s land-planning efforts, prompting the area to become known as the “A-bomb slum.”

Yutaka Ito, 75, who now lives in a municipal high-rise apartment building in Motomachi and operates a recycling business, used to live in a shelter on the banks of the Ota River. In 1952, when he was four years old, his family moved to Hiroshima from Akita in northern Japan, asking a family acquaintance for help. His parents started a wholesale business collecting waste materials to buy scrap iron and used paper, and expanded the business as the city’s reconstruction efforts accelerated after the war. Mr. Ito started helping out with the family business when he was a junior high-school student, and obtained a driver’s license for large trucks when he was a high school student. “My parents were pleased, and my family had enough to eat. That made me happy,” said Mr. Ito.

However, the local government decided to redevelop the Motomachi district to clear the densely packed, dilapidated shelters and slum area. Following the construction of municipal and prefectural mid-rise apartment buildings, high-rise buildings were built and residents of the dilapidated areas were encouraged to move into the new buildings. The Motomachi redevelopment project was declared finished in 1978.

On the site of such former public housing, which had been transformed into the city’s Central Park, the construction of a soccer stadium is now underway, against the backdrop of riverbanks lined with rows of cherry trees. Mr. Nakamura says, “I don’t want to allow the past to be whitewashed by people saying that Hiroshima has been perfectly reconstructed.” He continues to pass on the history of the post-war Motomachi district to ensure it is not erased from collective memory.

***

In the so-called “A-bomb slum” on the banks of the Ota River in the Motomachi area, in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward, fires broke out frequently. As a result of an influx of people into the district who had been evicted in the wake of land-planning efforts in various parts of the city, the area was densely packed with residents. The narrow roads made firefighting work difficult. During the 15 years from 1961 to 1976, there were 14 fires that burned down 403 housing units. One, a large fire in July 1967, burned down 149 residences. That situation served as a catalyst for the construction of high-rise apartment buildings.

Asako Lee, 78, who now lives in a municipal high-rise apartment building, witnessed one of the fires on the riverbank where she had lived for about five years. “When I ran to see if the fire was going to spread to my house, the area already resembled a tornado,” she said as she recalled the destructive blaze.

(Originally published on April 6, 2023)