Survivors’ Stories: Junko Yamase, 86, Naka Ward, Hiroshima City―Inspired by her friend, she began sharing her A-bomb account

Sep. 12, 2023

She returned to her hometown after turning to 80, and a desire for peace rose in her

by Kyoko Niiyama, Staff Writer

Junko Yamase (nee Saiki) was exposed to the atomic bombing at the age of eight and serves as one of the A-bomb Legacy Successors, a position she holds having been appointed by the Hiroshima City government. She began to share her A-bomb account at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward, as well as other locations about three years ago. It all started when she returned to her hometown of Hiroshima from the city of Shimonoseki, where she lived for a long time. Inspired by a friend who earlier had begun sharing her A-bomb account, continuing to advocate for the abolition of nuclear weapons, she decided to speak of her own A-bomb experience publicly.

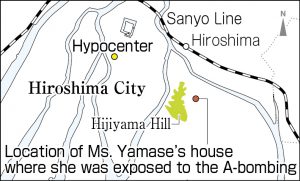

Back then, Ms. Yamase was a third grader at Kojinmachi National School (now in Minami Ward). Her house was in front of Hiroshima Station, but in the spring of 1945, she moved to the former Danbaranaka-machi (now part of Minami Ward) on the east side of Hijiyama Hill, 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. It was because her house was targeted for “demolition of buildings,” the dismantling of buildings and houses to create fire lanes so the spread of fire could be avoided in case of air strikes. She lived with a total of eight people: her paternal grandmother, her parents, and her five siblings.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, except for her grandmother and her second elder brother, who were in the suburbs, she was at home with her mother, her eldest brother, who was a second-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School), her 4-year-old sister, and her 2-year-old brother. Immediately after seeing a reflection of light on the windowpane, there was a tremendous sound, and she fell to the floor. Her house was escaped from complete destruction thanks to Hijiyama Hill.

When she got out onto the street in front of her house, she heard someone yelling, “Help!” Blood was spurting from the arm of a woman next door who was holding her child. Ms. Yamase’s mother stopped bleeding with a cotton towel she was wearing. The bright blue sky was covered with black clouds and turned dark, and she was horrified by the confusion among the people.

After a while, a truck passed in front of her. Covered in blood and dust, their clothes burnt and barely clinging to their bodies on the loading platform, the people remained completely still. When she turned her attention to Hijiyama Hill, she saw a wave of people fleeing from the west side. Ms. Yamase said, “I can still remember the image of people with both burned legs dragging their buttocks on the ground and moving forward using their hands.”

Her father, who was exposed to the A-bombing at the streetcar stop in Matoba-cho (now part of Minami Ward) on his way to work, returned home on the evening of August 6 with severe burns on his left arm. There was no medicine, and all they could do was remove the maggots from the affected area with chopsticks.

The war ended with the family of eight together, but her father had keloid scars on his arm and his skin was still fixed in bent position. Perhaps due to the effects of the A-bombing, he often fell ill. The breadwinner of the family was not able to work, causing hardship constantly.

Ms. Yamase got a job after graduating from high school. She moved to Shimonoseki in her mid-40s for her job. After turning to 80, she made a U-turn to spend the rest of her life with her siblings and friends.

One of her friends is Megumi Shinoda, 91, an A-bomb survivor living in Naka Ward. Ms. Yamase met her at a knitting class and saw her work as an A-bomb survivor who had been conveying her experience to the public for a long time. Ms. Shinoda’s desire for peace inspired her to pass on the reality of the A-bombing. Ms. Yamase responded to a call for applications from the Hiroshima City government, and after two years of training, she has been sharing her account with young people in and outside of Hiroshima Prefecture since 2020.

This summer, her eldest brother Mikio Saiki, 91, also aspired to be a Family A-bomb Legacy Successor and began receiving training from the city. When he saw Russian President Vladimir Putin hinting at the use of nuclear weapons after invading Ukraine, he was strongly motivated to convey the horror of nuclear weapons. Mikio, who was 13 years old at the time, remembers the time before and after the A-bombing well, and the brother and sister talked about the A-bombing. The determination of her brother who survived the A-bombing together is strengthening her resolve to “spread the cruelty of the A-bombing for the abolition of nuclear weapons, no matter how old we get.”

(Originally published on September 12, 2023)