Hiroshima Summit—Recovery after A-bombing, Part 6: Medical care for A-bomb survivors

Apr. 5, 2023

Private-practice physician verified high incidences of cancers among A-bomb survivors

by Kei Kinugawa and Yota Baba, Staff Writers

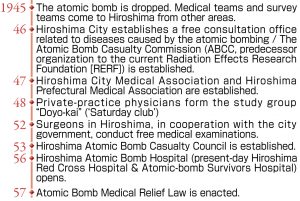

After the atomic bomb was dropped on the Hiroshima, the city’s system of health care faced many challenges. Because local emergency-care physicians had been prohibited from evacuating at times of air strikes, 270 of the 298 physicians in Hiroshima were affected by the atomic bombing, leaving the city bereft of physicians in the aftermath.

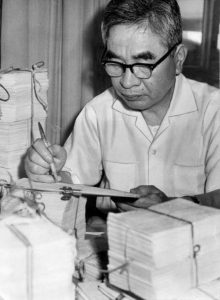

After the war’s end, Dr. Gensaku Oho had been discharged from military service and was staying at his home in Saga Prefecture at the time of the bombing. However, when his patients asked for his help, he returned to Hiroshima. In later years, he left a legacy in the area of research into health effects from the bombing. In July 1946, he resumed seeing patients at his home in the area of Midori-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), sometimes examining as many as 200 patients a day. Nobuyoshi Oho, 78, Gensaku’s fourth son who now lives in Minami Ward, looked back on that time. “People in Japan were poor in those days. My father’s patients often couldn’t pay their medical bills and many would bring him vegetables or fish instead.”

Dr. Oho wrote death certificates for patients on a nearly daily basis using the terminology ‘malignant anemia’ and ‘leukemia.’ He began to suspect that A-bomb survivors had higher incidences of disease. His suspicion turned into conviction when he started participating in a study group called the “Doyo-kai” (in English, the ‘Saturday club’), established by eight private-practice physicians in 1948, and shared information about patient cases with the others, including Tomin Harada, a surgeon, and Akira Masaoka, an obstetrician gynecologist.

With the idea that a statistical study was the only way to prove his theory, Dr. Oho hired a part-time worker at his own expense set about scrutinizing around 11,400 death certificates received by the city during the period 1951–1955. Dr. Oho also visited bereaved family members and the treating medical institutions to confirm how those who died experienced the atomic bombing, their symptoms, and the cause of their death. From that work, he published a paper in a medical journal showing for the first time that cancer mortality rates of A-bomb survivors were higher than the national average.

The paper was considered heresy even by some in the medical community. The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC; present-day Radiation Effects Research Foundation [RERF], located in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), an organization established by the United States government, dismissed the finding, arguing “Cancers are common in the elderly.” Dr. Oho, however, never yielded to the criticism. With the belief that the increased incidences would be swept under the rug unless someone studied the issue, he continued his analysis of the data. Ultimately, he found that “the longer the survivors stayed after entering the city following the bombing, the more they developed cancer.”

“Dr. Oho made great contributions in establishing the concept of exposure to radiation from the atomic bombing upon entry into the city [after the bombing]. Not limited to the patients he treated himself, he would visit the homes of those who had died and gain information such as the name of the disease and the circumstances under which they experienced the bombing. His approach to gathering the information was truly amazing,” explained Nanao Kamata, professor emeritus at Hiroshima University, in praise of Dr. Oho’s accomplishment. ABCC came to acknowledge that A-bomb survivors had indeed increased incidences of thyroid and lung cancers, in accordance with Dr. Oho’s hypothesis.

Many local physicians in Hiroshima engaged in the work of establishing an adequate system of medical care for A-bomb survivors. Takuso Yamawaki, a physician at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, reported for the first time that many cases of leukemia were being observed among A-bomb survivors. Fumio Shigeto, a physician who was Dr. Yamawaki’s superior, argued that a specialized hospital was needed to treat the A-bomb diseases and became the first director of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital (present-day Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital).

In 1953, a group of physicians formed the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council. Dr. Yoshimasa Matsusaka, chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association who led establishment of the organization, made an appeal to the national government, which led to free medical care for the A-bomb survivors as part of the national budget. Hiromi Nakayama, one of the members of the Doyo-kai study group, distributed to his patients an A-bomb survivor health record he himself had created. That record was the precursor to the A-bomb Survivor’s Certificates later issued by the national government based on the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law enacted in 1957.

The keloids that had formed on survivors’ faces or arms because of the atomic bombing had become a serious issue, especially for young women. After the Allied forces occupation of Japan ended in 1952 and the press code restricting media coverage and presentation on research findings from the damage caused by the atomic bombing was lifted, such women, called “Hiroshima maidens,” drew the public’s attention, which led to expansion of their circle of support.

With the media reporting the news that the Hiroshima maidens had received medical treatment in Tokyo or Osaka, criticism about the ineffectiveness of physicians in Hiroshima arose. Tomin Harada, a physician in Hiroshima, was inspired by the reaction and committed to conducting as many surgeries as possible. Based on the slogan “Medical treatment for survivors should be provided by physicians in Hiroshima,” Mr. Harada worked with his surgeon colleagues and took an organized approach toward achieving free treatment for survivors.

The United States also offered its support. In 1955, 25 single women traveled to the United States to undergo treatment for their keloids. The women were given the moniker the “Hiroshima girls” in the United States and, with that, they were able to raise awareness among the U.S. public of the existence of A-bomb survivors.

(Originally published on April 5, 2023)