HAC’s passion 50 years ago for imparting information on A-bombed Hiroshima, Part 1: 520 documents on bombing sent to US citizens

Jul. 25, 2023

Young people strove to summarize and translate materials into English

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

The book titles Black Rain by Masuji Ibuse and Hiroshima Diary by Michihiko Hachiya appear on a blueprint copy of a handwritten list of publications and materials involving the atomic bombing. The list represents part of materials sent to the Peace Resource Center (PRC) at Wilmington College in the U.S. state of Ohio by the Hiroshima Appeal Committee (HAC), which was established in the city 50 years ago. Confirmation has been made that the first 25 items were shipped in May 1974.

Active between 1973 and 1988

From 1973 to 1988, the HAC worked to communicate the reality of the atomic bombing to people in Japan and overseas. Materials that explain the group’s history are still archived at the World Friendship Center (WFC), located in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, an organization that took over the HAC’s work. Many of those that were involved in the HAC at that time are no longer alive, yet faint traces of the organization’s long forgotten history have come into focus.

Barbara Reynolds, a U.S. peace activist who died in 1990, was the one who requested that documents be sent to the PRC. In her efforts to support A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima, Ms. Reynolds founded the WFC, ultimately returning home to the United States in 1969. While putting her heart and soul into the anti-nuclear movement in the nuclear superpower that is America, she appears to have felt the need for a base from which to collect A-bomb materials and convey the threat of nuclear weapons. At her request, Tomin Harada, the first chairperson of the WFC who died in 1999, gathered together key individuals in the A-bombed city and launched the HAC. With the support of the Hiroshima City government, the group donated documents related to the atomic bombing.

With the donated documents, the PRC established a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Memorial Collection in 1975. However, a problem arose. An HAC report revealed that, with most of the materials in Japanese, only a limited number of people were able to access them. Starting in fiscal 1978, the HAC decided to summarize each of the Japanese-language materials into a wordcount of about 800 characters, translate that information into English, and send the summaries to the PRC.

The translation work was done by WFC members and young people who were proficient in English. At the WFC are materials handwritten in Japanese or typed in English containing the titles, bibliographic information, and summaries of about 109 such publications among 520 items in total the WFC had sent to the PRC by 1988.

Human resources trained to promote peace

No record exists of how many people were involved in what way or how the materials were used in the United States. But an unexpected byproduct of the project was indicated in the aforementioned report. “Careful reading is required to summarize the materials, and it gives young people translating them into English an opportunity to learn anew the significance of Hiroshima’s cause and the preciousness of peace.”

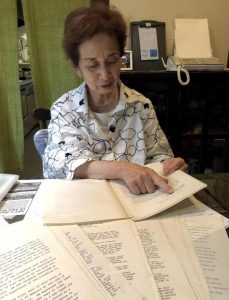

Tomoko Nakamura, the representative of LinguaHiroshima, an organization engaged in the creation of a database of A-bombing documents in multiple languages and the posting of the information on its website, was involved in the translation process. Looking back, she said, “I am what I am now thanks to that work.” One of her friends from long ago, Sadako Kurihara, an A-bomb survivor and poet who died in 2005, introduced her to the HAC. “If you are good at English, you should make use of it,” said Ms. Kurihara.

In those days, HAC’s organizational secretariat was located within the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, and Miyoko Matsubara, an A-bomb survivor who died in 2018, was in charge of administrative work. “I would go to the office and receive a summary from Ms. Matsubara, translate it, and bring it back to her, and then she would hand me the next one,” said Ms. Nakamura. Eventually she proposed that she do the work from the beginning, reading the documents carefully, making the summaries herself, and translating them into English. “I began to think more deeply about the tragedy the atomic bombing brought about and the lives of A-bomb survivors.” After she worked on 25 books in two years starting in 1981, Ms. Nakamura grew more interested and began making a list of documents related to the A-bombing in English, which led her to the research career she continues to this day.

Michiko Yamane, former chairperson of the WFC, also feels that her experience as an English translator in the WFC translation class between 1980 and 1987 led her on a path to her work over the next 40 years. Reuniting with the record of the group’s efforts, she remarked, “We must preserve and pass on the efforts of the people who came before us.”

Based on the materials found at the WFC and accounts provided by people involved, we will report on the passion of activists who made consistent efforts at the grassroots level to impart information about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima to people in Japan and overseas half a century ago, a time when the internet did not exist.

(Originally published on July 25, 2023)