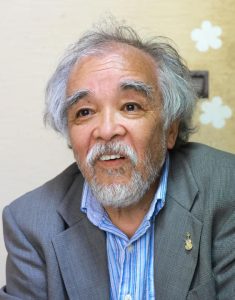

My guidepost, Hiroshima pioneers: Gataro, 73, painter, speaks about poet and painter Goro Shikoku

Sep. 25, 2023

Letting paint brush communicate unspoken wishes of the dead

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

For nearly 40 years, Gataro continued to work on his art while holding down a cleaning job. Since quitting his job three years ago, he devotes all of his time to his artwork. “After meeting Shikoku-sensei, I came to a strong awareness of the place I stand and breathe.” He creates art in pursuit of “the present” Hiroshima, which was destroyed in the atomic bombing in the past. “We should never forget the fact that countless dead are buried beneath our feet.”

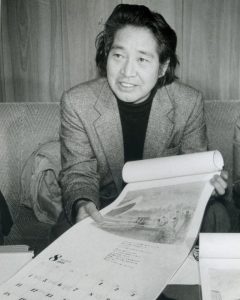

Shikoku-sensei is Goro Shikoku (1924–2014), an artist who was known in Hiroshima as a “citizen painter.” Throughout his life, Mr. Shikoku persisted in expressing his anti-war and anti-nuclear hopes through his paintings and writings. He is known for cover illustrations of the poet Sankichi Toge’s poetry collection titled Genbaku Shishu (in English, ‘Poems of the Atomic Bomb’) and the children’s book Okori Jizo (‘Angry jizo’).

Mr. Shikoku was born in present-day Daiwa-cho in Mihara City, Hiroshima Prefecture, and raised in Hiroshima City. Blessed with natural artistic talent, he wanted to be a painter since childhood, but the times did not allow the achievement of his dream. Having gone through a near-death experience in military service and internment in Siberia, he managed to return to Hiroshima after the end of World War II. At that time, he was informed of his beloved younger brother’s death in the atomic bombing. Driven by his grief about the atomic bombing and war, which unjustly rob people of life, he set about creating numerous works of art. He planted roots in the A-bombed Hiroshima and distanced himself from the co-called “art world” in Japan.

Gataro met his teacher in the mid-1980s. At a library, when he first gazed upon the collection of Mr. Shikoku’s pictures and writings titled Hiroshima Hyakkyo (in English, ‘One hundred bridges of Hiroshima’), he was “intuitively overwhelmed.” From that one book, in which were described bridges in Hiroshima, “I became aware of Mr. Shikoku’s natural gift, like breathing, for illustration and his well-considered, indigenous ideological foundation.” He also happened across an impressive sentence that read, “If someone living in this city [Hiroshima] does not sensitively respond to phenomena that could lead to war or stand on the side of preventing war, that person is no longer human.”

Just as Gataro decided he wanted to meet Mr. Shikoku and learn from the artist, he discovered news about the Peace Art Exhibition, held in Hiroshima every summer since Mr. Shikoku and his colleagues initiated the event in 1955. The announcement advertised a project to draw portraits of residents at a nursing home for A-bomb survivors. Assuming he would be able to meet Mr. Shikoku at the venue, he went the nursing home unannounced. He ultimately declared himself to be Mr. Shikoku’s apprentice and began to follow the artist around.

On the day he visited Mr. Shikoku’s studio, the artist showed him a nearly 1,000-page, hand-written biography titled Waga Seishun no Kiroku (‘Record of my youth’), created in a style akin to an illustrated diary. He was exposed to his teacher’s horrific experiences in and anger about war and to his determination to describe them quietly and in detail through his artwork.

His teacher, who was old enough to be his father, came to stand in for Gataro’s own dad, who died around the same time. Gataro’s father, a lacquerware craftsperson who had experienced the atomic bombing near the hypocenter, rarely shared his experience in the bombing, merely describing it as “the end of the world.” Through Mr. Shikoku, Gataro learned of details about Hiroshima’s atomic bombing, a situation his own father had been reluctant to speak about, and began to depict it in his own art.

In the publication Hiroshima Hyakkyo (‘One hundred bridges of Hiroshima’), Mr. Shikoku described bridges. “They dutifully handle their roles without asserting themselves,” he wrote.

“Bridges allow people to pass from both right and left without asserting themselves,” explained Gataro. “From my perspective, Mr. Shikoku has qualities of a bridge.” Having worked for the Hiroshima City office, Mr. Shikoku gracefully accepted many requests for his artwork, including for flyers, illustrations, and posters, on his condition, “If for a peaceful world.” Through his art, wordlessly, he connected people.

His bridge-like teacher said one thing should never be allowed to pass. “That was the power to wage war,” Gataro explained. “Mr. Shikoku said that once such power was allowed to pass, the bridge itself would be destroyed.” With his teacher’s comment in mind, Gataro remains sensitive to the risks that permeate the world. He cannot hold back his anger about the fact that the summit meeting of the G7 (Group of Seven industrialized nations), held in the A-bombed city, adopted a document premised on “nuclear deterrence.”

“What comes after that? Our imagination is now being put to the test,” said Gataro. Donning a keepsake jacket from his teacher, Gataro continues to create his art.

Profile

Gataro

Born in Hiroshima City in 1949, Gataro has drawn illustrations since childhood. At high school, he formed an art club on his own and became the leader of the group. After graduating from high school, he started work at a printing company in Osaka. He switched jobs several times before finally returning to his hometown of Hiroshima. Starting in the mid-1980s, he was active as a “janitor artist” while working as a cleaner at city-managed, high-rise condominiums in the area of Motomachi. After quitting his cleaning job, he now devotes all of his time to his art. While holding solo and group exhibits in Japan and overseas, he lives in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward.

Keywords

Goro Shikoku and Sankichi Toge

Goro Shikoku joined the activities of a gathering of poets to publish the group’s magazine Warera no Uta (in English, ‘Our poems’), which poet Sankichi Toge (1917–1953) began to release in 1949 after Mr. Shikoku had been discharged from military service and returned to Hiroshima in 1948. Under the controls on freedom of speech put in place during Japan’s occupation, the group members collaborated on Tsuji-shi (‘Street poems’), which involved combining poems and illustrations into a poster and posting the art on the streets. Mr. Shikoku provided a cover illustration and binding for the first edition of Mr. Toge’s Genbaku Shishu (‘Poems of the Atomic Bomb’), published in 1951, and also designed Mr. Toge’s poem monument in Peace Memorial Park, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

(Originally published on September 25, 2023)