An anti-nuclear life, Part 1: Shuichi Kato (commentator, 1919–2008)

Jan. 23, 2024

by Masakazu Domen, Senior Staff Writer

Among cultural figures and scientists active in literature, philosophy, punditry, and the arts, some achieved greatness in their words, deeds, and works based on their experiences in or consciousness about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the anti-nuclear movement. In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun hopes to delve into the image of such individuals and, based on their stories, ask questions about modern society, which continues to suffer from repeated conflict and an inability to eliminate nuclear weapons.

Shuichi Kato, a commentator and author known for such works as A History of Japanese Literature and A Sheep’s Song: A Writer’s Reminiscences of Japan and the World, confidently put forth essays and reviews on modern themes in genres ranging from literature to politics, while also serving as a lecturer at universities in Japan and overseas. He became known as a quintessential intellectual of post-war Japan.

Mr. Kato was originally a medical scientist with a specialty in hematology. He began to dedicate himself to work as a commentator and author in 1958, when he was in his late 30s. His career-shift is assumed to have been largely prompted by exposure to Western culture through his three-year education in France, beginning in 1951. Other factors might also have influenced his career decision, including his experience in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing during October–November 1945.

On August 6, 1995, the 50th anniversary of the bombing, Mr. Kato spoke in Hiroshima about his experience in detail. As one of the panelists at the Hiroshima World Citizens’ Forum, organized by the Hiroshima City government and the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, he appeared on stage and traced his memories of having stood on the scorched ruins of the city.

At that time, after the bombing, Mr. Kato was in his mid-20s and employed at a medical clinic affiliated with the Medical College of Tokyo Imperial University (present-day University of Tokyo). He was participating in a joint Japan-U.S. survey team set up to investigate the effects of the atomic bombing by order of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). Together with Masao Tsuzuki, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University, and other members of the survey team, he set about the work of examining A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima.

“Hiroshima had been completely flattened, except for some blackened trees standing here and there and crumbled walls of concrete,” described Mr. Kato. From his place at the forum, he shared his memories of the shocking scenes he had witnessed at that time. He also described the contradiction he had faced “between my scientific survey work and mission as a physician and empathy I felt while treating the sufferers as human beings.”

“Patients just kept coming. From the perspective of our survey, it was best to dispassionately examine them, record their status, and perform analysis,” described Mr. Kato. “However, coming into contact with those in pain is accompanied by human emotion.” He added, “If I were to describe the experience in general terms, I would say that there arose a contradiction between scientific rationality and human emotional response.”

He explained how he had long held that experience inside of himself. “It probably remains there still now,” said Mr. Kato. His lengthy confessional, balancing reason and emotion, was likely affected by the space and time of being in Hiroshima on the 50th anniversary of the city’s atomic bombing.

The Research Center for Shuichi Kato and the Japanese Contemporary Thoughts is located on the campus of Ritsumeikan University, in Kyoto’s Kita Ward, the university where Mr. Kato lectured as a visiting professor. The center was founded in 2015 as a venue to study and utilize Mr. Kato’s collection of books and manuscripts donated to the university after his death.

Found among his posthumous manuscripts were notes he had composed mainly in English for the forum held in Hiroshima on the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing. The notes contained the essence of his talk for that day, including ideas referred to as “science research and human sentiments” and “rationality vs. heart.”

How much weight did Mr. Kato place on his experience in the A-bombed Hiroshima? Tsutomu Washizu, 79, is the current director of the center who once worked on the publication of Mr. Kato’s writings as editor. “I believe his experience in Hiroshima must have been one of the reasons he abandoned his pursuit of a career as a physician,” he explained.

Mr. Washizu said, “In Hiroshima, he was faced with an insurmountable gap between the reality that ‘humans’ in the entirety of their human nature experienced the atomic bombing and that he, as a physician, had to consider A-bomb survivors merely as ‘cases’.” Mr. Kato was not only intelligent enough to identify the significance of that gap but also sensitive enough to perceive it as pain. Mr. Washizu added, “From that, we can understand why he moved in the direction of literature, which observes the totality of humanity.” Mr. Kato utilized his sharp analytical and reasoning skills to formulate essays in the humanities that gained him international acclaim.

In 2004, Mr. Kato took the lead in establishing the Article 9 Association, a group formed to protect the pacifism outlined in Japan’s Constitution, with a focus on that document’s Article 9. Listed as one of the group’s founders, which also included author Kenzaburo Oe (1935–2023), he unhesitatingly made his mind up to travel on a lecture tour across Japan starting in his mid-80s.

The group’s policy of staunchly defending Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution was criticized by some as unrealistic idealism. Nevertheless, Yoichi Komori, 70, the group’s secretary-general, said, “Mr. Kato logically analyzed post-war Japanese history and the political situation back then and ultimately launched a campaign underpinned by his judgment based on realism.” Mr. Komori hypothesized, “As someone who had experienced post-bombing Hiroshima, he seemed to me to lack the ability to simply remain an observer.”

At a lecture he delivered at an Article 9 Association event, Mr. Kato reconfigured the Latin proverb, “If you want peace, prepare for war.” His revised version read, “If you prepare for war, it is likely that there will be war. If peace is desired, it is better to prepare for peace.”

Since Mr. Kato’s death, 15 years have passed. The Japanese government has begun moves to expand the national defense budget, based on the justification that the world’s security environment has become increasingly dangerous. Mr. Kato’s aforementioned adage seems to have been a foreshadowing of the present. But it also serves as encouragement to those who are busy preparing for peace not war. It incorporates both reason and emotion.

Profile

Shuichi Kato

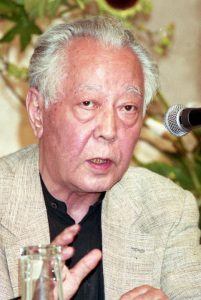

Born in Tokyo, Shuichi Kato graduated from the Imperial University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Medicine. Mr. Kato opened new horizons for the interpretation of Japanese culture through his work on “hybrid-culture” theory. He educated students at several institutes of higher learning, including Sophia University and Ritsumeikan University as well as at universities in Canada, Germany, and the United States. The attached photograph was taken in 1995 as he spoke at the Hiroshima World Citizens’ Forum, held in Hiroshima City.

(Originally published on January 23, 2024)

Among cultural figures and scientists active in literature, philosophy, punditry, and the arts, some achieved greatness in their words, deeds, and works based on their experiences in or consciousness about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the anti-nuclear movement. In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun hopes to delve into the image of such individuals and, based on their stories, ask questions about modern society, which continues to suffer from repeated conflict and an inability to eliminate nuclear weapons.

As physician in A-bombed Hiroshima, confronted “entirety of human nature”

Shuichi Kato, a commentator and author known for such works as A History of Japanese Literature and A Sheep’s Song: A Writer’s Reminiscences of Japan and the World, confidently put forth essays and reviews on modern themes in genres ranging from literature to politics, while also serving as a lecturer at universities in Japan and overseas. He became known as a quintessential intellectual of post-war Japan.

Mr. Kato was originally a medical scientist with a specialty in hematology. He began to dedicate himself to work as a commentator and author in 1958, when he was in his late 30s. His career-shift is assumed to have been largely prompted by exposure to Western culture through his three-year education in France, beginning in 1951. Other factors might also have influenced his career decision, including his experience in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing during October–November 1945.

On August 6, 1995, the 50th anniversary of the bombing, Mr. Kato spoke in Hiroshima about his experience in detail. As one of the panelists at the Hiroshima World Citizens’ Forum, organized by the Hiroshima City government and the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, he appeared on stage and traced his memories of having stood on the scorched ruins of the city.

At that time, after the bombing, Mr. Kato was in his mid-20s and employed at a medical clinic affiliated with the Medical College of Tokyo Imperial University (present-day University of Tokyo). He was participating in a joint Japan-U.S. survey team set up to investigate the effects of the atomic bombing by order of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). Together with Masao Tsuzuki, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University, and other members of the survey team, he set about the work of examining A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima.

“Hiroshima had been completely flattened, except for some blackened trees standing here and there and crumbled walls of concrete,” described Mr. Kato. From his place at the forum, he shared his memories of the shocking scenes he had witnessed at that time. He also described the contradiction he had faced “between my scientific survey work and mission as a physician and empathy I felt while treating the sufferers as human beings.”

“Patients just kept coming. From the perspective of our survey, it was best to dispassionately examine them, record their status, and perform analysis,” described Mr. Kato. “However, coming into contact with those in pain is accompanied by human emotion.” He added, “If I were to describe the experience in general terms, I would say that there arose a contradiction between scientific rationality and human emotional response.”

He explained how he had long held that experience inside of himself. “It probably remains there still now,” said Mr. Kato. His lengthy confessional, balancing reason and emotion, was likely affected by the space and time of being in Hiroshima on the 50th anniversary of the city’s atomic bombing.

The Research Center for Shuichi Kato and the Japanese Contemporary Thoughts is located on the campus of Ritsumeikan University, in Kyoto’s Kita Ward, the university where Mr. Kato lectured as a visiting professor. The center was founded in 2015 as a venue to study and utilize Mr. Kato’s collection of books and manuscripts donated to the university after his death.

Found among his posthumous manuscripts were notes he had composed mainly in English for the forum held in Hiroshima on the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing. The notes contained the essence of his talk for that day, including ideas referred to as “science research and human sentiments” and “rationality vs. heart.”

How much weight did Mr. Kato place on his experience in the A-bombed Hiroshima? Tsutomu Washizu, 79, is the current director of the center who once worked on the publication of Mr. Kato’s writings as editor. “I believe his experience in Hiroshima must have been one of the reasons he abandoned his pursuit of a career as a physician,” he explained.

Mr. Washizu said, “In Hiroshima, he was faced with an insurmountable gap between the reality that ‘humans’ in the entirety of their human nature experienced the atomic bombing and that he, as a physician, had to consider A-bomb survivors merely as ‘cases’.” Mr. Kato was not only intelligent enough to identify the significance of that gap but also sensitive enough to perceive it as pain. Mr. Washizu added, “From that, we can understand why he moved in the direction of literature, which observes the totality of humanity.” Mr. Kato utilized his sharp analytical and reasoning skills to formulate essays in the humanities that gained him international acclaim.

In 2004, Mr. Kato took the lead in establishing the Article 9 Association, a group formed to protect the pacifism outlined in Japan’s Constitution, with a focus on that document’s Article 9. Listed as one of the group’s founders, which also included author Kenzaburo Oe (1935–2023), he unhesitatingly made his mind up to travel on a lecture tour across Japan starting in his mid-80s.

The group’s policy of staunchly defending Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution was criticized by some as unrealistic idealism. Nevertheless, Yoichi Komori, 70, the group’s secretary-general, said, “Mr. Kato logically analyzed post-war Japanese history and the political situation back then and ultimately launched a campaign underpinned by his judgment based on realism.” Mr. Komori hypothesized, “As someone who had experienced post-bombing Hiroshima, he seemed to me to lack the ability to simply remain an observer.”

At a lecture he delivered at an Article 9 Association event, Mr. Kato reconfigured the Latin proverb, “If you want peace, prepare for war.” His revised version read, “If you prepare for war, it is likely that there will be war. If peace is desired, it is better to prepare for peace.”

Since Mr. Kato’s death, 15 years have passed. The Japanese government has begun moves to expand the national defense budget, based on the justification that the world’s security environment has become increasingly dangerous. Mr. Kato’s aforementioned adage seems to have been a foreshadowing of the present. But it also serves as encouragement to those who are busy preparing for peace not war. It incorporates both reason and emotion.

Profile

Shuichi Kato

Born in Tokyo, Shuichi Kato graduated from the Imperial University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Medicine. Mr. Kato opened new horizons for the interpretation of Japanese culture through his work on “hybrid-culture” theory. He educated students at several institutes of higher learning, including Sophia University and Ritsumeikan University as well as at universities in Canada, Germany, and the United States. The attached photograph was taken in 1995 as he spoke at the Hiroshima World Citizens’ Forum, held in Hiroshima City.

(Originally published on January 23, 2024)