Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Chugoku Shimbun and the Press Code — A-bombing articles subjected to censorship, especially those with keywords “atomic bombing”

Sep. 19, 2023

by Kazuo Yabui, Appointed Senior Staff Writer, the Chugoku Shimbun

The Japanese news media was constrained by the Press Code imposed on them by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) starting on September 19, 1945. During the nearly four years of censorship, some of the Chugoku Shimbun’s articles covering the atomic bombing were censored, while others were not. What can be gleaned from the different manners in which such articles were handled? The Chugoku Shimbun has conducted an analysis of that situation with a focus on the differences in frequency of keywords related to the atomic bombings appearing in the articles, as well as on the presence or absence of censorship by year of publication.

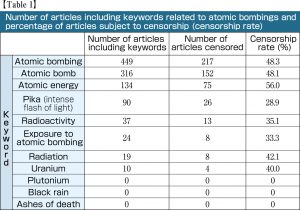

Among the Chugoku Shimbun articles covering the atomic bombing, what types of information was subject to censorship? Based on 11 keywords, we set about examining whether or not articles had been censored. The keywords were: atomic bombing, atomic bomb, atomic energy, pika (intense flash of light), radioactivity, A-bomb exposed, radiation, uranium, plutonium, black rain, and so-called ‘ashes of death’ (Table 1).

Our analysis covered 1,505 articles that had reported on the atomic bombing and were published between March 24, 1946, and October 13, 1949. That period corresponds to the publication dates of the Chugoku Shimbun articles stored in the Prange Collection at the U.S. University of Maryland, which has systematically archived Chugoku Shimbun articles that were censored at that time. When multiple keywords were included in one article, the article number was calculated on the basis of each of the individual keywords.

The keyword, or term, most frequently appearing in such articles was “atomic bombing.” The number of articles including that keyword totaled 449 among all the articles, resulting in a censorship rate of 48.3%. The next most frequent keyword was “atomic bomb,” appearing in 316 articles, at a censorship rate of 48.1%. With that, nearly half of the articles that included the terms “atomic bombing” or “atomic bomb” were found to have been censored. Conversely, even with those keywords, half of such articles had been labeled “censorship unnecessary” by censors at the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ).

Following the two aforementioned keywords was the phrase “atomic energy,” included in 134 of the articles. This term frequently appeared in articles reporting on development trends related to the nuclear rivalry between the United States and the former Soviet Union. The censorship rate of such articles was the highest of all keywords, at 56.0%.

“Pika,” used to refer to the “atomic bombing” at that time, appeared in 90 articles, leading to the assumption that the word had been used commonly among members of the public. The censorship rate related to that term was the lowest of all the keywords, at 28.9%, suggesting that articles including common terminology used by the general public generally escaped censorship. The number of articles that included “A-bomb exposed” was 24, suggesting that the phrase was not widely used at the time.

The term “radioactivity” appeared in 37 articles, while “radiation” was used in 19. Those numbers seem to indicate that “radioactivity” was used more frequently than the latter term. The censorship rate was higher for “radiation” than for “radioactivity” because “radiation” frequently appeared in medical papers involving health effects from the atomic bombing.

The phrases “ashes of death” and “black rain” had yet to appear. It was not until the U.S. hydrogen bomb testing was carried out on the Bikini Atoll in March 1954, when the Japanese tuna fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) was contaminated by radiation, that the issues of exposure to nuclear testing and residual radiation were brought to the public’s attention.

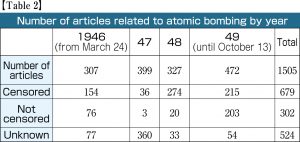

Next, we investigated whether censorship had taken place for articles on the atomic bombing by year (Table 2). However, for 1947, because only about one month’s worth of newspapers were found to have been archived in the Prange Collection, an accurate grasp on the actual extent of censorship was not possible.

For 1946, the ratio of the numbers of censored and uncensored articles was 2 to 1, with more articles being censored. However, for 1948, 274 articles were censored and 20 were not, indicating that a vast majority of the articles had been subject to censorship.

For 1949, 215 articles were censored compared to 203 that were not, a rate of nearly half and half, leaving the impression that censorship had been relaxed. By the end of October 1949, censorship had been halted nationwide.

Media also self-regulated from fear of repression

Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus, specialist in media censorship during Japan’s occupation, Waseda University Many of the documents in the possession of the occupying forces were incinerated or discarded as the occupation drew to a close. With that, the only option available was piecing together the remaining documents for analysis and research. Investigating the reality of censorship for one local newspaper could yield clues for understanding the impact of occupation policies in that specific region. The media were assumed to be more likely to undergo self-censorship of their reporting for fear of GHQ repression.

Valuable analysis for understanding impact on daily life

Satoru Ubuki, professor emeritus, specialist in Hiroshima’s A-bomb history, Hiroshima Jogakuin University

Although studies have been conducted previously on GHQ’s policies during the occupation period, few documents show in a comprehensive manner the local trends as can be understood from the results of this survey. In that regard, the work that has been carried out by the Chugoku Shimbun represents valuable analysis for understanding the impact of such occupation policies as censorship on the lives of ordinary people.

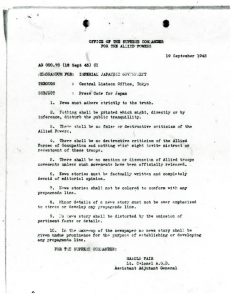

Full text of Press Code

1. News must adhere strictly to the truth.

2. Nothing shall be printed which might, directly or by inference, disturb the public tranquillity.

3. There shall be no false or destructive criticism of the Allied Powers.

4. There shall be no destructive criticism of the Allied Forces of Occupation and nothing which might invite mistrust or resentment of those troops.

5. There shall be no mention or discussion of Allied troops movements unless such movements have been officially released.

6. News stories must be factually written and completely devoid of editorial opinion.

7. News stories shall not be colored to conform with any propaganda line.

8. Minor details of a news story must not be over emphasized to stress or develop any propaganda line.

9. No news story shall be distorted by the omission of pertinent facts or details.

10. In the make-up of the newspaper no news story shall be given undue prominence for the purpose of establishing or developing any propaganda line.

(Source: Japanese Newspaper Annual 1947–1948)

*The Chinese characters used in the [original Japanese] text were modified to new, simplified characters.

Media bound under occupation for four years following GHQ directive

During World War II, the United States basically censored media in countries it occupied. In Japan, the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD), an executive unit under the auspices of GHQ, arrived in Yokohama City on September 1, 1945, the date marking the start of its activities. That was one day before the signing ceremony of Japan’s Instrument of Surrender to the Allied powers was held aboard the USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay.

On September 10, GHQ newly established the Press, Publications, and Broadcasting (PPB) Division within the CCD, with the aim of establishing a system of media censorship, and presented the censorship policy to the Japanese government as a directive.

The directive was known as the Memorandum on Freedom of Speech, which stipulated that, 1) the Japanese Imperial Government would issue the necessary orders to prevent dissemination of news, through newspapers, radio broadcasting, or other means of publication, which failed to adhere to the truth or disturbed public tranquility; 2) the freedom to discuss matters affecting the future of Japan would be encouraged by the Allied powers, unless such discussion was considered harmful to the efforts of Japan to emerge from defeat as a new nation entitled to a place among the peace-loving nations of the world; and 3) such subjects as discussions about Allied troop movements not officially released, false or destructive criticism of the Allied powers, as well as false rumors would not be allowed. The directive also stipulated that publications or radio stations would be suspended in cases in which they failed to adhere to the directive.

With the directive, censorship was effectively put in place.

On September 14, the Domei News Agency (predecessor to the present-day Kyodo News Service) was suspended for one day because it had distributed news that was considered harmful to “public tranquillity.” The Asahi Shimbun’s publishing on September 19 and 20th was suspended for the reason that five articles it had published between September 15 and 17th were in violation of the directive. The Asahi articles in question contained descriptions perceived to be critical of the dropping of the atomic bomb.

On September 19, GHQ also issued the “Press Code” for Japan (which is often translated into Japanese as ‘newspaper reporting standards,’ ‘newspaper laws applied to Japan,’ and so on), a document that embodied its policy of censorship. The press code consisted of 10 articles, representing a more detailed censorship policy than the directive itself.

In response to this GHQ policy, controls on the media in Tokyo started in the form of “pre-print censorship.” Newspaper and broadcasting companies submitted galley proofs and manuscripts to GHQ for censorship in advance of the release of any such information. Sections ordered to be deleted could not be printed or broadcast. Censorship by the Japanese military during the war involved the marking with a series of “xxx” on the text deemed to require censorship. In the case of GHQ, however, the media was forced to remove, rather than simply mark over, the censored sections before printing or broadcasting so that no trace of censorship remained.

In most local newspapers, censorship gradually began in the fall of 1945, later than the national newspapers, in the form of “post-print censorship.” However, the censorship required enormous time and effort and involved huge costs, which placed a significant burden on GHQ. As a result, censorship was ended at the end of October 1949, rather than at the end of the occupation, in April 1952.

Work of compiling databases of documents, publications archived at Prange Collection continues

After the occupation of Japan ended, a tremendous volume of documents and publications collected during the period of censorship carried out by GHQ between September 1945 and October 1949 was sent to the University of Maryland and archived by Dr. Gordon Prange, who during the occupation worked in the Military History Section for the Assistant Chief of Staff. That archive is what is now called the “Prange Collection,” named after Dr. Prange. Japan’s National Diet Library holds the originals for approximately 20% of the documents and publications held in the Prange Collection. The collections serve as a valuable resource for researching the media during the occupation period.

Later, because the documents and publications had begun to deteriorate, the University of Maryland and Japan’s National Diet Library set out to microfilm the material in 1992. As for newspapers, 3,826 microfilm reels, an estimated 1.7 million pages, and an estimated 26 million articles are stored at the Modern Japanese Political History Materials Room of Japan’s National Diet Library.

With respect to information in newspapers and magazines, a database project committee for the occupation period’s newspaper and magazine article information, composed of specialists and researchers (headed by Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus, Waseda University), created a database titled the 20th Century Media Information Database, which registers headlines, article leads, information on presence or absence of censorship, publication dates, publication pages, and other related data.

Pre-print censorship for magazines and others, post-print censorship for local newspapers

For magazines and publications, pre-print censorship was applied and, with that, two copies of galley proofs had to be submitted in advance. On the other hand, for newspapers, the two types of censorship were applied: both pre-print censorship, and post-print censorship following publication.

Pre-print censorship was generally applied to national newspapers, news agencies, and new newspapers that had emerged in Tokyo and Osaka after the war. Post-print censorship was applied to regional and local newspapers because it was difficult to establish pre-print censorship systems for local areas. The Chugoku Shimbun and the Yukan Hiroshima, a local evening newspaper, were subject to such post-print censorship.

Pre-print censorship required the submission of two copies of galley proofs. If information was given the judgment “partial deletion” or “publication prohibited,” the corresponding sections were deleted to ensure that readers would not detect any trace of censorship.

Some trade publications and news agencies were shifted to post-print censorship in November 1946, while many national newspapers and news agencies were designated for post-print censorship in July 1948.

Burden of censorship by field, region

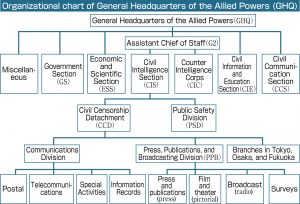

Within GHQ, the aforementioned CCD, a subordinate unit of the Civil Intelligence Section (CIS) under control of the Assistant Chief of Staff (G2), was tasked with the work of censorship.

The CCD was further divided into the Press, Publications and Broadcasting Division (PPB) and the Communications Division, an office that carried out the work of wiretapping telephones and opening mail. The PPB division had four sections: a press and publications office, a film and theater office, a broadcasting office, and a survey office.

The CCD divided up the mainland Japan into three districts for local censorship: 1) Tokyo as the headquarters of what was known as district 1; 2) Osaka, as district 2; and 3) Fukuoka, as district 3.

District 3 included the three prefectures of Hiroshima, Yamaguchi and Shimane in the Chugoku Region and the seven prefectures in the Kyushu area, excluding Okinawa. The Chugoku Shimbun and the Yukan Hiroshima sent their two newspaper copies each day to the district 3 head offices in Fukuoka City. When there was a delay in submitting the news copies, a reminder letter would sometimes be sent.

Propaganda for “re-education” of Japanese people

In addition to the CCD, GHQ also housed the Civil Information and Education Section (CIE), which was responsible for propaganda to instill a sense of guilt and responsibility about the war among the Japanese people.

According to GHQ no Kennetsu, Choho, Senden Kosaku (in English, ‘Censorship, Intelligence and Propaganda of GHQ’) written by Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus at Waseda University and a specialist in media censorship during the occupation period, the CIE fell under direct control of GHQ and was responsible for changing the minds of and reeducating Japanese people in the fields of information, education, religion, culture, the arts, public opinion polls, and sociological surveys.

In 1948, prior to the final arguments of prosecutors and final defense pleas made at the Tokyo Trials, the CIE became concerned that sympathy for Japan’s former Prime Minister Hideki Tojo might grow and that criticism of the United States, the country that had dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, would increase.

The need for new propaganda efforts was pointed out, and Hiroshima was mentioned as a target of such propaganda.

(Originally published on September 19, 2023)

The Japanese news media was constrained by the Press Code imposed on them by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) starting on September 19, 1945. During the nearly four years of censorship, some of the Chugoku Shimbun’s articles covering the atomic bombing were censored, while others were not. What can be gleaned from the different manners in which such articles were handled? The Chugoku Shimbun has conducted an analysis of that situation with a focus on the differences in frequency of keywords related to the atomic bombings appearing in the articles, as well as on the presence or absence of censorship by year of publication.

Among the Chugoku Shimbun articles covering the atomic bombing, what types of information was subject to censorship? Based on 11 keywords, we set about examining whether or not articles had been censored. The keywords were: atomic bombing, atomic bomb, atomic energy, pika (intense flash of light), radioactivity, A-bomb exposed, radiation, uranium, plutonium, black rain, and so-called ‘ashes of death’ (Table 1).

Our analysis covered 1,505 articles that had reported on the atomic bombing and were published between March 24, 1946, and October 13, 1949. That period corresponds to the publication dates of the Chugoku Shimbun articles stored in the Prange Collection at the U.S. University of Maryland, which has systematically archived Chugoku Shimbun articles that were censored at that time. When multiple keywords were included in one article, the article number was calculated on the basis of each of the individual keywords.

The keyword, or term, most frequently appearing in such articles was “atomic bombing.” The number of articles including that keyword totaled 449 among all the articles, resulting in a censorship rate of 48.3%. The next most frequent keyword was “atomic bomb,” appearing in 316 articles, at a censorship rate of 48.1%. With that, nearly half of the articles that included the terms “atomic bombing” or “atomic bomb” were found to have been censored. Conversely, even with those keywords, half of such articles had been labeled “censorship unnecessary” by censors at the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ).

Following the two aforementioned keywords was the phrase “atomic energy,” included in 134 of the articles. This term frequently appeared in articles reporting on development trends related to the nuclear rivalry between the United States and the former Soviet Union. The censorship rate of such articles was the highest of all keywords, at 56.0%.

“Pika,” used to refer to the “atomic bombing” at that time, appeared in 90 articles, leading to the assumption that the word had been used commonly among members of the public. The censorship rate related to that term was the lowest of all the keywords, at 28.9%, suggesting that articles including common terminology used by the general public generally escaped censorship. The number of articles that included “A-bomb exposed” was 24, suggesting that the phrase was not widely used at the time.

The term “radioactivity” appeared in 37 articles, while “radiation” was used in 19. Those numbers seem to indicate that “radioactivity” was used more frequently than the latter term. The censorship rate was higher for “radiation” than for “radioactivity” because “radiation” frequently appeared in medical papers involving health effects from the atomic bombing.

The phrases “ashes of death” and “black rain” had yet to appear. It was not until the U.S. hydrogen bomb testing was carried out on the Bikini Atoll in March 1954, when the Japanese tuna fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) was contaminated by radiation, that the issues of exposure to nuclear testing and residual radiation were brought to the public’s attention.

Next, we investigated whether censorship had taken place for articles on the atomic bombing by year (Table 2). However, for 1947, because only about one month’s worth of newspapers were found to have been archived in the Prange Collection, an accurate grasp on the actual extent of censorship was not possible.

For 1946, the ratio of the numbers of censored and uncensored articles was 2 to 1, with more articles being censored. However, for 1948, 274 articles were censored and 20 were not, indicating that a vast majority of the articles had been subject to censorship.

For 1949, 215 articles were censored compared to 203 that were not, a rate of nearly half and half, leaving the impression that censorship had been relaxed. By the end of October 1949, censorship had been halted nationwide.

Media also self-regulated from fear of repression

Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus, specialist in media censorship during Japan’s occupation, Waseda University Many of the documents in the possession of the occupying forces were incinerated or discarded as the occupation drew to a close. With that, the only option available was piecing together the remaining documents for analysis and research. Investigating the reality of censorship for one local newspaper could yield clues for understanding the impact of occupation policies in that specific region. The media were assumed to be more likely to undergo self-censorship of their reporting for fear of GHQ repression.

Valuable analysis for understanding impact on daily life

Satoru Ubuki, professor emeritus, specialist in Hiroshima’s A-bomb history, Hiroshima Jogakuin University

Although studies have been conducted previously on GHQ’s policies during the occupation period, few documents show in a comprehensive manner the local trends as can be understood from the results of this survey. In that regard, the work that has been carried out by the Chugoku Shimbun represents valuable analysis for understanding the impact of such occupation policies as censorship on the lives of ordinary people.

Full text of Press Code

1. News must adhere strictly to the truth.

2. Nothing shall be printed which might, directly or by inference, disturb the public tranquillity.

3. There shall be no false or destructive criticism of the Allied Powers.

4. There shall be no destructive criticism of the Allied Forces of Occupation and nothing which might invite mistrust or resentment of those troops.

5. There shall be no mention or discussion of Allied troops movements unless such movements have been officially released.

6. News stories must be factually written and completely devoid of editorial opinion.

7. News stories shall not be colored to conform with any propaganda line.

8. Minor details of a news story must not be over emphasized to stress or develop any propaganda line.

9. No news story shall be distorted by the omission of pertinent facts or details.

10. In the make-up of the newspaper no news story shall be given undue prominence for the purpose of establishing or developing any propaganda line.

(Source: Japanese Newspaper Annual 1947–1948)

*The Chinese characters used in the [original Japanese] text were modified to new, simplified characters.

Media bound under occupation for four years following GHQ directive

During World War II, the United States basically censored media in countries it occupied. In Japan, the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD), an executive unit under the auspices of GHQ, arrived in Yokohama City on September 1, 1945, the date marking the start of its activities. That was one day before the signing ceremony of Japan’s Instrument of Surrender to the Allied powers was held aboard the USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay.

On September 10, GHQ newly established the Press, Publications, and Broadcasting (PPB) Division within the CCD, with the aim of establishing a system of media censorship, and presented the censorship policy to the Japanese government as a directive.

The directive was known as the Memorandum on Freedom of Speech, which stipulated that, 1) the Japanese Imperial Government would issue the necessary orders to prevent dissemination of news, through newspapers, radio broadcasting, or other means of publication, which failed to adhere to the truth or disturbed public tranquility; 2) the freedom to discuss matters affecting the future of Japan would be encouraged by the Allied powers, unless such discussion was considered harmful to the efforts of Japan to emerge from defeat as a new nation entitled to a place among the peace-loving nations of the world; and 3) such subjects as discussions about Allied troop movements not officially released, false or destructive criticism of the Allied powers, as well as false rumors would not be allowed. The directive also stipulated that publications or radio stations would be suspended in cases in which they failed to adhere to the directive.

With the directive, censorship was effectively put in place.

On September 14, the Domei News Agency (predecessor to the present-day Kyodo News Service) was suspended for one day because it had distributed news that was considered harmful to “public tranquillity.” The Asahi Shimbun’s publishing on September 19 and 20th was suspended for the reason that five articles it had published between September 15 and 17th were in violation of the directive. The Asahi articles in question contained descriptions perceived to be critical of the dropping of the atomic bomb.

On September 19, GHQ also issued the “Press Code” for Japan (which is often translated into Japanese as ‘newspaper reporting standards,’ ‘newspaper laws applied to Japan,’ and so on), a document that embodied its policy of censorship. The press code consisted of 10 articles, representing a more detailed censorship policy than the directive itself.

In response to this GHQ policy, controls on the media in Tokyo started in the form of “pre-print censorship.” Newspaper and broadcasting companies submitted galley proofs and manuscripts to GHQ for censorship in advance of the release of any such information. Sections ordered to be deleted could not be printed or broadcast. Censorship by the Japanese military during the war involved the marking with a series of “xxx” on the text deemed to require censorship. In the case of GHQ, however, the media was forced to remove, rather than simply mark over, the censored sections before printing or broadcasting so that no trace of censorship remained.

In most local newspapers, censorship gradually began in the fall of 1945, later than the national newspapers, in the form of “post-print censorship.” However, the censorship required enormous time and effort and involved huge costs, which placed a significant burden on GHQ. As a result, censorship was ended at the end of October 1949, rather than at the end of the occupation, in April 1952.

Work of compiling databases of documents, publications archived at Prange Collection continues

After the occupation of Japan ended, a tremendous volume of documents and publications collected during the period of censorship carried out by GHQ between September 1945 and October 1949 was sent to the University of Maryland and archived by Dr. Gordon Prange, who during the occupation worked in the Military History Section for the Assistant Chief of Staff. That archive is what is now called the “Prange Collection,” named after Dr. Prange. Japan’s National Diet Library holds the originals for approximately 20% of the documents and publications held in the Prange Collection. The collections serve as a valuable resource for researching the media during the occupation period.

Later, because the documents and publications had begun to deteriorate, the University of Maryland and Japan’s National Diet Library set out to microfilm the material in 1992. As for newspapers, 3,826 microfilm reels, an estimated 1.7 million pages, and an estimated 26 million articles are stored at the Modern Japanese Political History Materials Room of Japan’s National Diet Library.

With respect to information in newspapers and magazines, a database project committee for the occupation period’s newspaper and magazine article information, composed of specialists and researchers (headed by Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus, Waseda University), created a database titled the 20th Century Media Information Database, which registers headlines, article leads, information on presence or absence of censorship, publication dates, publication pages, and other related data.

Pre-print censorship for magazines and others, post-print censorship for local newspapers

For magazines and publications, pre-print censorship was applied and, with that, two copies of galley proofs had to be submitted in advance. On the other hand, for newspapers, the two types of censorship were applied: both pre-print censorship, and post-print censorship following publication.

Pre-print censorship was generally applied to national newspapers, news agencies, and new newspapers that had emerged in Tokyo and Osaka after the war. Post-print censorship was applied to regional and local newspapers because it was difficult to establish pre-print censorship systems for local areas. The Chugoku Shimbun and the Yukan Hiroshima, a local evening newspaper, were subject to such post-print censorship.

Pre-print censorship required the submission of two copies of galley proofs. If information was given the judgment “partial deletion” or “publication prohibited,” the corresponding sections were deleted to ensure that readers would not detect any trace of censorship.

Some trade publications and news agencies were shifted to post-print censorship in November 1946, while many national newspapers and news agencies were designated for post-print censorship in July 1948.

Burden of censorship by field, region

Within GHQ, the aforementioned CCD, a subordinate unit of the Civil Intelligence Section (CIS) under control of the Assistant Chief of Staff (G2), was tasked with the work of censorship.

The CCD was further divided into the Press, Publications and Broadcasting Division (PPB) and the Communications Division, an office that carried out the work of wiretapping telephones and opening mail. The PPB division had four sections: a press and publications office, a film and theater office, a broadcasting office, and a survey office.

The CCD divided up the mainland Japan into three districts for local censorship: 1) Tokyo as the headquarters of what was known as district 1; 2) Osaka, as district 2; and 3) Fukuoka, as district 3.

District 3 included the three prefectures of Hiroshima, Yamaguchi and Shimane in the Chugoku Region and the seven prefectures in the Kyushu area, excluding Okinawa. The Chugoku Shimbun and the Yukan Hiroshima sent their two newspaper copies each day to the district 3 head offices in Fukuoka City. When there was a delay in submitting the news copies, a reminder letter would sometimes be sent.

Propaganda for “re-education” of Japanese people

In addition to the CCD, GHQ also housed the Civil Information and Education Section (CIE), which was responsible for propaganda to instill a sense of guilt and responsibility about the war among the Japanese people.

According to GHQ no Kennetsu, Choho, Senden Kosaku (in English, ‘Censorship, Intelligence and Propaganda of GHQ’) written by Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus at Waseda University and a specialist in media censorship during the occupation period, the CIE fell under direct control of GHQ and was responsible for changing the minds of and reeducating Japanese people in the fields of information, education, religion, culture, the arts, public opinion polls, and sociological surveys.

In 1948, prior to the final arguments of prosecutors and final defense pleas made at the Tokyo Trials, the CIE became concerned that sympathy for Japan’s former Prime Minister Hideki Tojo might grow and that criticism of the United States, the country that had dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, would increase.

The need for new propaganda efforts was pointed out, and Hiroshima was mentioned as a target of such propaganda.

(Originally published on September 19, 2023)