Chosei coal mine disaster 82 years on — Remains of victims left buried at sea, Part 1: Korean victims

Feb. 1, 2024

Mine remnants carry silent message of suffering from victims that torments bereaved families

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

During World War II, there was an accident in an undersea coal mine in Ube City in Yamaguchi Prefecture that led to the deaths of 183 mine workers, 136 of whom (more than 70 percent) were Koreans. The remains of the victims still lie at sea, unrecovered. This coming February 3 marks 82 years since the accident. Bereaved family members and a local civic group have continued to call on Japan’s national government to exhume the remains and return them to their families.

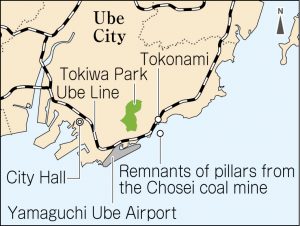

In Nishikiwa in Yamaguchi Prefecture’s Ube City, near the Yamaguchi Ube Airport, two concrete pillars jut out from the sea several tens of meters from the beach. The pillars are remnants of ventilation and drainage shafts from mine tunnels. Beneath the ordinarily calm sea was located the Chosei coal mine.

On December 8 last year, a civic group based in Ube City that works to memorialize the history of the Chosei coal mine flooding disaster joined with members of an association of Korean bereaved families of victims of the disaster. The two groups faced off against officials from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare at the office building of Japan’s House of Representatives, in Tokyo.

Mine entrance remains closed

“The pillars are sending a silent message to the victims’ families. It’s as if the screams and voices of resentment from that day pierce my heart,” said Yang Hyeon, 76, president of the association of bereaved Korean families, as he called for the exhumation of his uncle, Yang Imsu, 20 at the time of the disaster, and others who died in the accident. It was the third meeting, and the first in five years, that the civic group had with the government but the first attended by members of the Korean families association.

On the morning of February 3, 1942, an emergency occurred at the Chosei undersea coal mine, when a tunnel located about one kilometer from the aboveground mine entrance collapsed and flooded. According to the civic group, it was a day in which more coal than usual was set to be mined out, with the coal supports for the ceiling also removed, which is believed to have been one cause of the accident. The next day, February 4, the mine entrance was closed up, leaving the workers behind. That entrance remains closed to this day. Mining work continued after the accident through a newly opened entrance, but the company managing the mine halted operations after the war.

People from the Korean peninsula made up most of the workers in the Chosei coal mine. Ube-shi Shi (in English, ‘A History of Ube City’), published in 1993, describes the situation in the following ways — “The tragedy of Korean laborers forcibly taken to Japan,” and, “Japanese mine workers feared the Chosei mine, known as a dangerous undersea coal mine with particularly shallow tunnels, so Koreans were forced to work there. It was pejoratively dubbed the ‘Korean coal mine’ at that time.”

Living in horse stable at friend’s house

At the meeting with the government, the civic group also presented letters from bereaved families. After Jeon Seokho, 90, lost his then 42-year-old father, Jeon Seongdo, his family was evicted from company housing and lived in a stable for horses at a friend’s house. When they returned to Korea after the war, he began working as a servant. Regarding that time, he wrote, “I collected wood in the mountains as I watched my friends go to school. I cried and blamed my father, but it wasn’t his fault.”

One family continues to hold on to a letter that Kim Wondal, then 27, sent his mother before the accident, in which he described life in the Chosei coal mine. “The housing is like a prison camp, surrounded by fences about three meters high made of thick pine and wrapped tightly with barbed wire.” He added, “They use violence against us and, since we are not given enough to eat, I’m hungry most of the time.” The letter concluded, “I’ll get out of here and return to you, mother.”

His remains lie in the cold sea off the coast of Ube City.

Keywords

Coal mining industry in Ube City

The Ube coalfield, stretching about 10 kilometers from east to west, is believed to have been mined as early as the beginning of the Edo era (1603–1868). Coal was used in salt production throughout the Seto Inland Sea area in the mid-Edo era. The coal mining industry grew in importance in the Meiji era (1868–1912), as Japan industrialized. Coal was mined even from coal seams under the seabed. The quickly urbanized village of Ube was designated a city without undergoing the intermediate designation of a town. At its peak in 1940, the Ube coalfield produced 4.23 million tons of coal, but the mine was closed in 1967 due to the transition to energy from petroleum.

(Originally published on February 1, 2024)