My guidepost, Hiroshima pioneers: Laid foundation for A-bomb survivors’ movement through calls from Hiroshima

Jan. 8, 2024

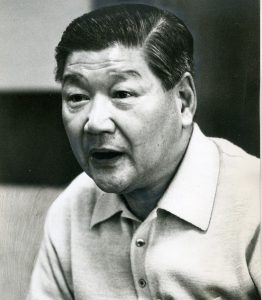

Satoru Ubuki, 77, historian of Hiroshima A-bombing, speaks about Heiichi Fujii

by Hiromi Morita and Kana Kobayashi, Staff Writers

From the time the atomic bomb survivors, without government support, suffered from the aftereffects of the bombing and abject poverty, there were people who voiced their opinions publicly and worked fervently to lead a campaign for recognition of their plight. Calling on the public for support of the survivors, those pioneers united the A-bomb survivors, paving the way for aid and relief and educating the public about the “absolute evil” represented by nuclear weapons. Now, a time when the world is reeling from persistent wars and concerns about the use of nuclear weapons, we hope to look back at the origins of the A-bombed Hiroshima’s story.

Brought to public attention the cry “restore Hiroshima as it was”

Even now, after retiring from his post as an academic, Mr. Ubuki continues to handle large volumes of materials and to communicate information through his website “Hiroshima Ibun” (in English, ‘Literary remains of A-bombed Hiroshima’), which traces the postwar history of the A-bombed city using words and materials that remain behind as clues to those times.

Among the countless pioneers with whom he became acquainted as a researcher was someone he calls his guidepost. Heiichi Fujii (1915–1996) strove to form the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo) and served as the first secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). Said Mr. Ubuki, “I would say that my research career into the A-bombed Hiroshima became what it is alongside Mr. Fujii. Whenever I hit an impasse, I always think about what he would have done.”

In 1977, while working at Hiroshima University’s Data and Specimens Center of Atomic Bomb Disaster in the university’s Research Institute for Nuclear Medicine and Biology (present-day Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine), Mr. Ubuki started to organize and investigate two cardboard boxes’ worth of Mr. Fujii’s materials. The collection of documents communicated the origins of the A-bomb survivors’ movement, including memos related to Mr. Fujii’s involvement in the founding of Hiroshima Hidankyo and Nihon Hidankyo in 1956. Starting in 1981, Mr. Ubuki spent much of his time interviewing Mr. Fujii.

Mr. Fujii would use the phrase “restore Hiroshima as it was” to represent the heartrending voices of victims of the atomic bombing about the injured and the dead. He was in Tokyo on the day of the bombing, August 6, 1945, and was therefore not designated an A-bomb survivor under administrative law. However, his family lived in downtown Hiroshima while managing a store that specialized in decorative woods. His father and older sister were killed in the atomic bombing. After Japan’s defeat in the war, Mr. Fujii returned to his hometown to rebuild the family business. In his role as a member of a local welfare committee, Mr. Fujii learned of the difficulties that the victims of the bombing faced in Hiroshima. He poured so much of his energy into the movements to support A-bomb survivors and to ban A- and H-bombs that the family business began to suffer.

Mr. Ubuki’s interviews were conducted on the basis of materials and chronological record of the steps Mr. Fujii had taken. Mr. Fujii was in his late 60’s at the time and had already retired from the front lines of the movement, but he readily accepted Mr. Ubuki’s request for information. “I want to leave a written record,” said Mr. Fujii. He explained a variety of things, including what had gone on behind the scenes.

Mr. Fujii’s stories included his support of Ichiro Moritaki, secretary general of the first World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, held in Hiroshima in 1955, which represented a first step in making the world aware of the suffering of those victimized by the atomic bombing, as well as descriptions of his fund-raising efforts. He also described how he united the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki based on the idea that, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki are like two wheels that must move in unison.” He talked about compiling the desperate demands of A-bomb survivors and, as head of the delegation, presenting a petition to Japan’s parliamentary Diet, an act that resulted in enactment of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law in 1957.

Mr. Ubuki worked to confirm some of the details of the interviews, which also required supplementary information. Mr. Fujii also gave him a lot of homework. “He introduced me to people and took me places where I could access materials. After a while, I became something like a secretary to him,” said Mr. Ubuki.

The results of the interviews, recorded on a total of 60 120-minute tapes, were published in the Hiroshima University Data and Specimen Center’s Shiryo Chosa Tsushin (‘Data and Research News’) in issues No. 5 (issued December 1981) through No. 29 (January 1984) under the title “Restore Hiroshima as it was — Conversations with Heiichi Fujii.”

With a boisterous voice and a caring personality, Mr. Fujii had formed many connections in government through his alma mater’s Acacia-kai (present-day alumni association of Hiroshima University Junior and Senior High School) and through his Waseda University connections. He worked behind the scenes for those in need and publicly offered his support for others in the organization. He also called for the establishment of Sekai Hidankyo, a global organization of nuclear victims, to help the increasing number of victims of worldwide nuclear testing carried out after the war.

“We have so much to learn from Mr. Fujii, someone who valued people and relationships and saw the world from the viewpoint of the A-bombed city,” explained Mr. Ubuki, who came into contact with Mr. Fujii’s organizational ability and learned about his thought process. “He was the first person to speak out in public for those victimized by the atomic bombing. He laid the foundation for the A-bomb survivors’ movement.”

Mr. Ubuki has continued to hold on to the words spoken by Mr. Fujii — “Turn the history of common people into world history.” That statement is illustrative of his idea that history should not be rendered only by those with power, the ability to write, and the ability to speak. “Mr. Fujii did what he had to do and, with that, I will do what I can.” Every day, he updates his website with the knowledge he has accumulated as a historian to ensure that future generations can use the information as a gateway for learning about the A-bombed Hiroshima.

Satoru Ubuki

Born in Kure City in Hiroshima Prefecture, Mr. Ubuki graduated from Kyoto University in 1969. He specialized in the history of postwar Japan and of the atomic bombing. Starting in 1970, he worked for the Hiroshima Prefectural government’s historiographic division, working on and writing such papers as “A-bombing Documents.” After working as an assistant professor at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Nuclear Medicine and Biology (present-day Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine), Mr. Ubuki served as a professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University until 2011. He is the author of many publications, including Hiroshima Sengoshi (‘History of Postwar Hiroshima’).

Keywords

Former Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law

The former Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law defined the term “A-bomb survivor” and led to the issuance of Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificates, providing those recognized as being survivors with regular health examinations and medical benefits. The law was significant in that, from that point, the government officially recognized those who, more than 10 years after the bombing, were still suffering from the aftereffects of their exposure to A-bomb radiation, providing them with health care and medical treatment. In 1994, the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law was enacted after integration of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law and the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law, which had been established in 1968.

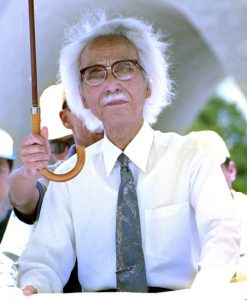

Tetsuo Kaneko, 75, representative member, Hiroshima Prefectural Chapter of Japan Congress against A- and H-Bombs, speaks about Ichiro Moritaki

Calls from A-bombed city serve as foundation of campaign

From the time A-bomb survivors, without government support, suffered from the aftereffects of the bombing and poor living conditions, some people voiced their opinions publicly and worked fervently to lead a campaign for recognition of their plight. Calling on the public for support of the survivors, those pioneers united the A-bomb survivors, paving the way for relief and educating the public about the “absolute evil” represented by nuclear weapons. Now, a time when the world is reeling from persistent wars and concerns about the use of nuclear weapons, we hope to look back at the origins of A-bombed Hiroshima’s story.

Demonstrate ideology and philosophy through action

“Life is precious” is a motto used by Ichiro Moritaki (1901–1994), an ethicist who experienced the A-bombing tragedy and spearheaded the campaign to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs. Tetsuo Kaneko has been conscious of those words both during his long involvement in the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs and during his single term as a member of Japan’s House of Representatives between 2000 and 2003.

“Mr. Moritaki valued life above all else and questioned a society built at the expense of people in vulnerable positions,” said Mr. Kaneko. He added, “He vehemently opposed nuclear weapons and war and continued to warn that ‘humanity cannot coexist with nuclear weapons.’ That sentiment serves as the starting point of my own activities.”

Mr. Moritaki, who served as the first secretary general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hidankyo) and in other posts, lost sight in his right eye in the atomic bombing at the age of 44, when he was an instructor at the Hiroshima Higher Normal School (present-day Hiroshima University). At the time of the bombing, he was escorting students mobilized in the war effort to their work site. After Japan’s defeat in the war, he would reflect on his deep remorse for having played a part in the nation’s militaristic education system. Reaching the conclusion that a major change in values was necessary for humanity to survive, he argued for and acted to bring about a transition from a “civilization of power” dependent on nuclear weapons and military force to a “civilization of love.”

From his position as professor, Mr. Moritaki launched a “moral adoption” campaign in Japan to provide emotional and financial support to A-bomb orphans. He also proposed that a World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs be held in Hiroshima, successfully organizing the first such conference in 1955. In 1956, he endeavored with Heiichi Fujii and others to establish the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). He worked passionately to call on Japan to establish the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law based on the “spirit of national reparation” as a responsibility for the country’s involvement in the war.

Mr. Kaneko first met Mr. Moritaki about half a century ago. He joined a sit-in in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, to protest nuclear testing as a member of the labor union of the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation (present-day NTT). Mr. Kaneko observed Mr. Moritaki from a vantage point close behind him. “Mr. Moritaki was sitting with back ramrod straight in the front row and didn’t move an inch,” described Mr. Kaneko.

The two grew closer in the 1980s. In response to unprecedented momentum in Europe’s anti-nuclear movement, Mr. Moritaki, other scholars, and cultural leaders lobbied for hosting the Rally for Peace in Hiroshima. The rally, ultimately held in 1982, brought around 200,000 people to Peace Memorial Park and other locations in Hiroshima. At the rally event and at the Hiroshima World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, for which Mr. Kaneko worked in the secretariat, the two began to speak. Mr. Kaneko was attracted to Mr. Moritaki’s personality because, he said, “He never acted arrogantly even when speaking with young people like myself.”

Mr. Moritaki turned his attention to the assortment of nuclear problems around the world, such as uranium mining, nuclear weapons development, and nuclear power accidents. In 1987, Mr. Kaneko accompanied Mr. Moritaki to the First Global Radiation Victims Conference in New York City, a gathering Mr. Moritaki helped organize. Mr. Kaneko’s memories of the event are a mixed bag of regret and happiness. He had intended to attend the conference alongside Mr. Moritaki, who was already elderly. Despite that, however, “I was laid up in bed with a stomachache. I’ll never forget the warmth of his hands, though, as he tried to help me by massaging my stomach.”

The most significant lesson he learned from Mr. Moritaki was an attitude of self-reflection. “It is difficult for anyone to admit mistakes. But Mr. Moritaki was able to do that even after achieving the status he enjoyed.” Mr. Moritaki had once supported the war and, for a time after the war, also acknowledged the peaceful use of nuclear energy. His reflection on his former positions resulted in his absolute rejection of nuclear weapons and nuclear power. He led A-bomb survivor delegations on visits to China, interacting with survivors of the Nanking Massacre, an atrocity committed by the former Imperial Japanese Army. Feeling responsible for the split that occurred in the movement to ban A- and H-bombs due to internal conflicts over whether to oppose the former USSR’s nuclear testing, he devoted himself to seeking ways to reunify the different camps.

“I want to demonstrate my philosophy though action,” Mr. Kaneko explains. As an example, while serving as a member of Japan’s House of Representatives, he focused on relief measures for overseas A-bomb survivors who were at the time ineligible for support from the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law and, toward that end, assumed the position of chief of secretariat of a bipartisan parliamentarian council with that aim. He continues to participate in such activities as sit-ins and rallies to express his anti-war and anti-nuclear stances.

Thirty years have passed since Mr. Moritaki’s death. “Emphasizing that the power of the people itself is a deterrent, Mr. Moritaki worked to pave the way for the abolition of nuclear weapons through actions in solidarity with citizens,” said Mr. Kaneko. He believes that, “While the power inherent in each individual is weak, persistent efforts will alter society’s faith in nuclear weapons.”

Tetsuo Kaneko

Born in Izumo City, Mr. Kaneko graduated from Shimane Prefectural Izumo High School and was transferred to Hiroshima after being hired by the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation. He left the company in 1981 and became a full-time employee at the Hiroshima prefectural headquarters of the former Socialist Party of Japan. He also served as assistant director-general of the Hiroshima chapter of Gensuikin as well as in posts at other organizations. In 2000, he ran for a seat in Japan’s House of Representatives as a member of the Social Democratic Party and was elected in proportional representation of the Chugoku block. He served one term. Mr. Kaneko has served in his current post since 2014. He is a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

Keywords

Sit-ins in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims with A-bomb survivors

In March 1957, four people, including Kiyoshi Kikkawa, known as “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1,” carried out a sit-in lasting around one month to protest the United Kingdom’s hydrogen bomb testing. In 1962, Mr. Moritaki conducted a sit-in with Mr. Kikkawa over a span of 12 days in response to the U.S. plan to resume atmospheric nuclear weapons testing. At that time, a young girl remarked, “Just sitting there won’t stop nuclear testing.” In response, Mr. Moritaki set about explaining the significance of non-violent solidarity and protest. Still today, A-bomb survivor groups carry out sit-ins each time a nuclear test is conducted.

(Originally published on January 8, 2024)