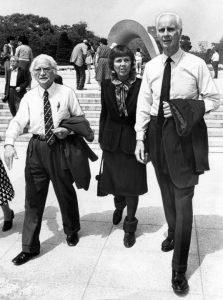

My guidepost, Hiroshima pioneers: Setsuko Thurlow, 92, A-bomb survivor, speaks about Kiyoshi Tanimoto, Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church minister

Feb. 19, 2024

Tanimoto aimed to base anti-nuclear campaign on love and action

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Seventy years ago, Setsuko Thurlow made the decision to travel to the United States to study abroad. After moving to Canada, where she now lives, Ms. Thurlow continued to speak of her experiences in the atomic bombing and to call for the elimination of nuclear weapons. Despite the worldwide recognition she has gained, her anti-nuclear efforts have not always gone smoothly in North America, given the region’s entrenched public sentiment in support of the bombings.

Whenever she felt as if she could go no further, Ms. Tanimoto reminded herself of the expression “belief together with love and action.” Those words were spoken by and acted upon by Kiyoshi Tanimoto (1909–1986), minister at the Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church. “That is the origin of the activism that runs through my life,” said Ms. Thurlow.

Mr. Tanimoto was described in Hiroshima, the acclaimed account of the city written by John Hersey, who died in 1993, after he had interviewed and reported on A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima in 1946. Taking advantage of his name recognition, Mr. Tanimoto called for “no more Hiroshimas” throughout Japan and in the United States. He also worked to promote what was called a ‘moral adoption’ movement, in which U.S. citizens would provide both financial and psychological support to A-bomb orphans. For A-bombed women who suffered from burn scars called ‘keloids’ on their faces, he strove to enable them to obtain medical treatment in Tokyo and New York City.

“He was always so busy,” said Ms. Thurlow, as she recalled her memories of Mr. Tanimoto. “Though many criticized him for not being a minister who stayed at the church preparing for Sunday sermons, he ignored them, saying that ‘without action or practice, it is not true faith,’” she explained. “His unwavering adherence to his own beliefs was impressive.”

Mr. Tanimoto lost many of the members of his church in the atomic bombing 79 years ago. “But my family and I survived,” he would say. The starting point of his post-war activities was his experience of and sense of guilt about not having been able to save the lives of victims.

The English proficiency he had developed in his studies at Kwansei Gakuin University, located in Hyogo Prefecture, and in his study abroad in the United States proved to be of great value to him. Mr. Tanimoto made his first post-war visit to the United States in 1948. Upon invitation of the Methodist Church, he shared with Americans the reality of Hiroshima over the course of 15 months, during which he raised funds for reconstruction of his church. With a strong desire to establish the Hiroshima Peace Center as a base for activities related to peace studies and aid for A-bomb survivors, he worked on deepening partnerships with Americans of renown.

Ms. Thurlow’s first contact with Mr. Tanimoto took place when she was a high school student. She had lost nine relatives in the atomic bombing, including her older sister and a four-year-old nephew, as well as friends from school. With that experience, she set about seeking the meaning in why she alone was able to survive. She began attending Nagarekawa Church and was baptized just before turning 17.

At university, she would read the Bible to children at Sunday school and help translate documents from the United States and letters that American parents in the moral adoption campaign had written to A-bomb orphans. “Mr. Tanimoto gave me numerous opportunities to volunteer,” said Ms. Thurlow.

She said she also owes Mr. Tanimoto a personal debt of gratitude. During the same period, she met a Canadian English teacher at Kwansei Gakuin Junior High School. The two found they were attracted to each other, but her parents were fiercely opposed to their relationship. It was then that she traveled alone to the United States based on a plan that had already been decided to study abroad. The following year, she received the unexpected news from Japan that Mr. Tanimoto had convinced her parents to allow her marriage to the man, Jim Thurlow, who died in 2011. For her, he was a beloved husband as well as an ally in anti-nuclear work.

“Mr. Tanimoto came to America to attend my wedding,” said Ms. Thurlow. “I got to where I am today thanks to him.” Nevertheless, she acknowledged that, “We had differences in the direction we hoped to take our peace movements.”

When touring the United States, in an attempt to seek reconciliation between Japan and the United States, Mr. Tanimoto told Americans that “A-bomb survivors do not feel animosity toward you.” He insisted that the basic attitude for achieving international understanding was “to not judge.” In contrast, in her own activities, Ms. Thurlow has called out the responsibility of the world’s nuclear powers. From the podium when she spoke at the award ceremony for the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize, she criticized those “who still refused to see Hiroshima and Nagasaki as atrocities — as war crimes.” She spoke on behalf of the anger of the voiceless dead.

Regardless of such differences, Mr. Thurlow said, “Nobody else could have visited America from occupied Japan, been accepted by the American people, and conveyed the reality of Hiroshima the way he did.” In America, a country basking in the glow of the victory over Japan in the war, Mr. Tanimoto gave a listen to both citizens who felt agonized by the tragedy of the A-bombed city as well as to the former crew of the planes that dropped the atomic bombs.

The moral adoption initiative cast light on the existence of people who were being left behind in post-war reconstruction. His fight for the provision of medical treatment to young female survivors who had developed keloids triggered establishment in Japan of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law, the first post-war legal framework for providing relief to A-bomb survivors. “I have visited many places in the United States over many years and, everywhere I go, I find his name,” said Ms. Thurlow. Those footsteps of someone Ms. Thurlow calls “a person who should be held in higher regard” still remain both in Japan and the United States.

Profile

Setsuko Thurlow

Born in Hiroshima, Ms. Thurlow graduated from Hiroshima Jogakuin University and later earned a master’s degree in social welfare at the University of Toronto in Canada. She started work for the Toronto Board of Education as a school social worker. She delivered a speech at the award ceremony of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the international NGO International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). Ms. Thurlow now lives in Toronto.

Keywords

Hiroshima Peace Center

Mr. Tanimoto called for establishment of the Hiroshima Peace Center as a way for the city to contribute to global peace. The initial concept for the center included a research institute and a hospital. Mr. Tanimoto’s allies, including the literature Nobel laureate Pearl S. Buck and the journalist Norman Cousins, formed a collaborative group in the United States in 1949 to support establishment of the center. Founded in 1950, the peace center in Japan served as the contact point for the moral adoption program. Now, the center sponsors the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize. Mr. Cousins was the first recipient of the prize and Ms. Thurlow the 26th awardee.

(Originally published on February 19, 2024)