Contents of letters written by Peace Park designer Kenzo Tange disclosed

Jan. 16, 2009

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Letters written by Kenzo Tange, designer of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, have been preserved in the city’s archives it was recently learned. Mr. Tange, an internationally renowned architect who died in 2005 at the age of 91, was chosen to design the park in 1949. Thus began a roughly two-year correspondence with the late Shinso Hamai, then the city’s mayor, and others. The city is considering making public the contents of the letters, which have been held in the archives under the stipulation that their contents remain undisclosed until after Mr. Tange’s death. The letters, the only remaining correspondence by Mr. Tange, reveal previously unknown information related to the construction of the park, now one of the nation’s most famous landmarks.

Mr. Tange, an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo, sent 22 letters and one postcard to Mr. Hamai, who had gained fame as the mayor of an A-bombed city, and other city employees. Most of the letters were handwritten. Chimata Fujimoto, 92, who worked in the mayor’s office at the time, donated the letters to the city in 1989. The letters describe Mr. Tange’s ideas about the park during its construction, including his belief that it should be a symbol of everlasting peace and recovery. He also wrote about his work in Tokyo.

In a letter dated May 27, 1950, the year after his design was selected, Mr. Tange described a conversation he had had with Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), who worked on the design for the Peace Bridge. Mr. Noguchi suggested that Mr. Tange incorporate a slope into the park’s plaza, and Tange conveyed his desire to do so to the city. This may have led to his decision to put steps leading up to the memorial cenotaph from the plaza to its south.

In a letter to the mayor believed to have been written in September 1950, Mr. Tange described his concern about world affairs following the outbreak of the Korean War three months before and his determination to create a city of peace. The letter also recounts other little known facts, such as how Mr. Tange used his connections in the Ministry of Construction to get a subsidy from the government to build a meeting hall in the park to serve as a “base for the peace movement.”

Mr. Tange, who spent his student days in Hiroshima before the war, referred to the city as his “second home.” He proposed a design in which the Atomic Bomb Dome, memorial cenotaph, and museum could be seen along a straight line and put this idea to use. Mr. Tange’s letters reveal his extraordinary passion for the project.

The city is considering making the letters public in conjunction with events marking this year’s 60th anniversary of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, which provided the driving force for the building of the park.

Terunobu Fujimori, a professor at the Institute of Industrial Science of Tokyo University and a specialist in architectural history, said, “No other group of postwar letters by Tange has been preserved. They are first-rate materials. His enthusiasm for the plan for Hiroshima comes across in the letters.”

Kenzo Tange

Born in Osaka in 1913. Graduated from the former Hiroshima High School (forerunner of Hiroshima University) and Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). With his design of Peace Memorial Park and other projects, he became one of Japan’s most famous postwar architects. While serving as a professor at the University of Tokyo, he designed the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and created the master plan for the site of Expo ’70, the world’s fair held in Osaka in 1970. In 1991 he designed the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building. He was awarded the Order of Culture in 1980.

Peace Memorial Park

Shortly after the war, the city of Hiroshima conceived building a park in the Nakajima district, which had been devastated by the atomic bombing, and in 1949 designs were solicited from architects throughout Japan. Kenzo Tange’s design was selected from among 145 proposals. Based on the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, which was enacted in August of the same year, construction of the park began using a special subsidy from the government. By 1955 the Peace Memorial Museum and the Municipal Auditorium had been completed.

(Originally published on January 9, 2009)

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Kenzo Tange’s letters reveal that sculptor Isamu Noguchi made a suggestion about the design for Peace Memorial Park.

In a letter dated May 27, 1950, Mr. Tange described his historic meeting with Mr. Noguchi, which had taken place in Japan earlier that month. “I met Isamu Noguchi the other day… He looked at pictures of the model of the Peace Memorial Hall [now part of the Peace Memorial Museum], and we had a very pleasant conversation.”

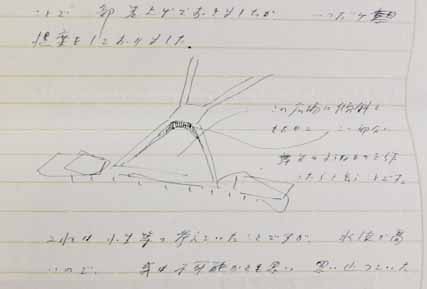

A letter Mr. Tange sent to the city includes a sketch showing the park’s plaza at a lower level than the central area where the memorial cenotaph stands now. “He says I should put a slope in the plaza to create a sort of stage,” Mr. Tange wrote in describing the only suggestion that Mr. Noguchi made. “I’ll look into this, and if it’s possible I’d like to do it,” Mr. Tange added.

Photos of the model Mr. Tange made in 1949 at the time of the design contest show neither a slope nor steps. These were added to the design later and incorporated into the park. It is likely that Mr. Tange proposed these changes as a result of his conversation with Mr. Noguchi.

In 1951, at Mr. Tange’s request, Mr. Noguchi created a design for the memorial cenotaph, but it was not accepted because he was a citizen of the country which had dropped the atomic bomb. The letters, however, show once again how Mr. Noguchi is tied to Hiroshima through Mr. Tange.

(Originally published January 9, 2009)

Related articles

International entries in design competition for new pedestrian bridge by the Peace Bridge (Dec. 16, 2008)

Exhibition on Isamu Noguchi, designer of the Peace Bridge (Dec. 13, 2008)

Letters written by Kenzo Tange, designer of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, have been preserved in the city’s archives it was recently learned. Mr. Tange, an internationally renowned architect who died in 2005 at the age of 91, was chosen to design the park in 1949. Thus began a roughly two-year correspondence with the late Shinso Hamai, then the city’s mayor, and others. The city is considering making public the contents of the letters, which have been held in the archives under the stipulation that their contents remain undisclosed until after Mr. Tange’s death. The letters, the only remaining correspondence by Mr. Tange, reveal previously unknown information related to the construction of the park, now one of the nation’s most famous landmarks.

Mr. Tange, an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo, sent 22 letters and one postcard to Mr. Hamai, who had gained fame as the mayor of an A-bombed city, and other city employees. Most of the letters were handwritten. Chimata Fujimoto, 92, who worked in the mayor’s office at the time, donated the letters to the city in 1989. The letters describe Mr. Tange’s ideas about the park during its construction, including his belief that it should be a symbol of everlasting peace and recovery. He also wrote about his work in Tokyo.

In a letter dated May 27, 1950, the year after his design was selected, Mr. Tange described a conversation he had had with Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), who worked on the design for the Peace Bridge. Mr. Noguchi suggested that Mr. Tange incorporate a slope into the park’s plaza, and Tange conveyed his desire to do so to the city. This may have led to his decision to put steps leading up to the memorial cenotaph from the plaza to its south.

In a letter to the mayor believed to have been written in September 1950, Mr. Tange described his concern about world affairs following the outbreak of the Korean War three months before and his determination to create a city of peace. The letter also recounts other little known facts, such as how Mr. Tange used his connections in the Ministry of Construction to get a subsidy from the government to build a meeting hall in the park to serve as a “base for the peace movement.”

Mr. Tange, who spent his student days in Hiroshima before the war, referred to the city as his “second home.” He proposed a design in which the Atomic Bomb Dome, memorial cenotaph, and museum could be seen along a straight line and put this idea to use. Mr. Tange’s letters reveal his extraordinary passion for the project.

The city is considering making the letters public in conjunction with events marking this year’s 60th anniversary of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, which provided the driving force for the building of the park.

Terunobu Fujimori, a professor at the Institute of Industrial Science of Tokyo University and a specialist in architectural history, said, “No other group of postwar letters by Tange has been preserved. They are first-rate materials. His enthusiasm for the plan for Hiroshima comes across in the letters.”

Kenzo Tange

Born in Osaka in 1913. Graduated from the former Hiroshima High School (forerunner of Hiroshima University) and Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). With his design of Peace Memorial Park and other projects, he became one of Japan’s most famous postwar architects. While serving as a professor at the University of Tokyo, he designed the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and created the master plan for the site of Expo ’70, the world’s fair held in Osaka in 1970. In 1991 he designed the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building. He was awarded the Order of Culture in 1980.

Peace Memorial Park

Shortly after the war, the city of Hiroshima conceived building a park in the Nakajima district, which had been devastated by the atomic bombing, and in 1949 designs were solicited from architects throughout Japan. Kenzo Tange’s design was selected from among 145 proposals. Based on the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, which was enacted in August of the same year, construction of the park began using a special subsidy from the government. By 1955 the Peace Memorial Museum and the Municipal Auditorium had been completed.

(Originally published on January 9, 2009)

Suggestion from Noguchi resulted in steps leading up to cenotaph

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Kenzo Tange’s letters reveal that sculptor Isamu Noguchi made a suggestion about the design for Peace Memorial Park.

In a letter dated May 27, 1950, Mr. Tange described his historic meeting with Mr. Noguchi, which had taken place in Japan earlier that month. “I met Isamu Noguchi the other day… He looked at pictures of the model of the Peace Memorial Hall [now part of the Peace Memorial Museum], and we had a very pleasant conversation.”

A letter Mr. Tange sent to the city includes a sketch showing the park’s plaza at a lower level than the central area where the memorial cenotaph stands now. “He says I should put a slope in the plaza to create a sort of stage,” Mr. Tange wrote in describing the only suggestion that Mr. Noguchi made. “I’ll look into this, and if it’s possible I’d like to do it,” Mr. Tange added.

Photos of the model Mr. Tange made in 1949 at the time of the design contest show neither a slope nor steps. These were added to the design later and incorporated into the park. It is likely that Mr. Tange proposed these changes as a result of his conversation with Mr. Noguchi.

In 1951, at Mr. Tange’s request, Mr. Noguchi created a design for the memorial cenotaph, but it was not accepted because he was a citizen of the country which had dropped the atomic bomb. The letters, however, show once again how Mr. Noguchi is tied to Hiroshima through Mr. Tange.

(Originally published January 9, 2009)

Related articles

International entries in design competition for new pedestrian bridge by the Peace Bridge (Dec. 16, 2008)

Exhibition on Isamu Noguchi, designer of the Peace Bridge (Dec. 13, 2008)