Questions from Marshall Islands 70 years after Bikini Atoll disaster, Part 1: Residents of test site

Mar. 13, 2024

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

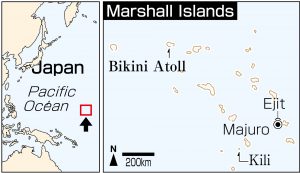

The United States conducted repeated nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands in the central Pacific Ocean. Former residents of the region, the site of nuclear weapons testing and on which fell radioactive “ashes of death,” as well as their descendants, are still unable to return home. The area faces issues of fading memories of the disaster and submergence of the islands by rising ocean levels due to climate change. On the 70th anniversary of the largest hydrogen bomb test conducted on Bikini Atoll, dubbed “Castle Bravo,” I visited the Marshall Islands to consider the unending nuclear damage experienced by the residents of the islands and the crews of Japanese fishing boats.

As soon as the prayers and the remarks made by the head of the local government concluded, lively dance music began. I got the sense that Marshallese love loud music. Women danced and tossed sweets, akin to Japanese ceremonies in which rice cakes are thrown to attendees, with children running around together to pick up the sweet treats. On the backs of their shirts were printed the words, “Everything is in God’s hands,” together with an image of a mushroom cloud.

United States explained testing was “for sake of humankind”

I witnessed that scene on March 7 in a public square on Ejit Island, the country’s capital and one of the islands in the Majuro Atoll. On this date 78 years ago, the 167 inhabitants of Bikini Atoll were forced to leave their homes in preparation for a series of nuclear tests conducted by the United States, which claimed the testing was being done for the sake of humankind. On this day, the former residents and their children gathered on Ejit, one of the places to which they had been relocated, in commemoration of a different “Bikini Day.” The other Bikini Day is March 1, marking the date that the Japanese tuna fishing boat the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (in English, ‘Lucky Dragon No. 5’), based out of Shizuoka Prefecture, and other fishing boats were exposed to radiation from the aforementioned hydrogen bomb test.

The father of Roney Joel, 62, a pastor at a church on Ejit, was originally from Bikini. Stacked up in the kitchen of his house, which he called a “temporary residence,” were cans of tuna, instant ramen, and frozen chicken bought in Majuro.

There is a lack of fresh fruit on Ejit. The immigrants continue to simply rent land in Majuro and are unable to fish the waters freely. Roney Joel lived on Bikini for several years after a “declaration of safety” was issued by the United States in 1968. During that time he learned of the richness of life on the atoll, with its scattered islands forming an arch shape and its inland sea. “I want to go back. I don’t care about the radiation,” he remarked forlornly.

According to the Bikini Atoll local government with jurisdiction over the former residents and their descendants, nine of the 167 people of Bikini displaced in 1946 are still alive. Five of that total still live in the Marshall Islands, with the rest in the United States for medical reasons. Meanwhile, the results of a study published by a U.S. university in 2019 showed that high levels of radiation remain on Bikini Atoll. Due to concerns about contamination, the U.S. government has not taken any concrete steps to repatriate the residents back to their home islands.

People’s lives hit hard by financial difficulties

Bikinians struggle with their daily lives while longing for home and, to make matters worse, the Bikini Atoll local government finds itself in difficult financial straits. Jack Niedenthal, 66, who had just started work with the local government, revealed to me in his office that he was using his own computer and printer because the purchase of office equipment was out of reach for the government.

As of 2017, there were 59 million dollars remaining in a trust fund established with compensation money paid by the United States in recognition of the damage caused by the nuclear tests. Now, however, the fund amount is close to zero, in part due to the alleged improper use of funds by a former local government leader. Cash payouts to residents every three months have been reduced to 25 dollars per person, 20 percent of the previous amount. With prices as high as 3.50 dollars for a bag of carrots, for example, people’s living standards are hard hit.

The situation on the isolated island of Kili, where around 250 evacuees and their family members live, is particularly serious. According to Jamore Winkel, 45, who moved from Kili to Majuro, where he now works as a public servant, people on the island faced starvation over the course of last year. Mr. Winkel described how the situation on the island this year has improved with government intervention.

Before all else, the islands are surrounded by the rough waters of the Pacific Ocean, making it impossible for people to fish or for boats to deliver food and fuel in stormy weather. Has the history of suffering for the people of the islands been of benefit to humanity? “I really don’t know,” replied Mr. Jamore, shrugging off my question with a wry smile.

Keywords

Nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands

The United States conducted 67 nuclear tests on Bikini and Enewetak atolls in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958. In particular, the yield of the hydrogen bomb used in a test known as “Castle Bravo,” conducted on March 1, 1954, was around 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, resulting in fallout of large amounts of radioactive “ashes of death.” In addition to the residents of the atolls, crews of the Japanese tuna fishing boat the Daigo Fukuryu Maru and other fishing boats operating near the test site were all exposed to radiation. Aikichi Kuboyama, then a 40-year-old radio operator on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, died six months later.

(Originally published on March 13, 2024)

The United States conducted repeated nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands in the central Pacific Ocean. Former residents of the region, the site of nuclear weapons testing and on which fell radioactive “ashes of death,” as well as their descendants, are still unable to return home. The area faces issues of fading memories of the disaster and submergence of the islands by rising ocean levels due to climate change. On the 70th anniversary of the largest hydrogen bomb test conducted on Bikini Atoll, dubbed “Castle Bravo,” I visited the Marshall Islands to consider the unending nuclear damage experienced by the residents of the islands and the crews of Japanese fishing boats.

Unfulfilled desire to return home

As soon as the prayers and the remarks made by the head of the local government concluded, lively dance music began. I got the sense that Marshallese love loud music. Women danced and tossed sweets, akin to Japanese ceremonies in which rice cakes are thrown to attendees, with children running around together to pick up the sweet treats. On the backs of their shirts were printed the words, “Everything is in God’s hands,” together with an image of a mushroom cloud.

United States explained testing was “for sake of humankind”

I witnessed that scene on March 7 in a public square on Ejit Island, the country’s capital and one of the islands in the Majuro Atoll. On this date 78 years ago, the 167 inhabitants of Bikini Atoll were forced to leave their homes in preparation for a series of nuclear tests conducted by the United States, which claimed the testing was being done for the sake of humankind. On this day, the former residents and their children gathered on Ejit, one of the places to which they had been relocated, in commemoration of a different “Bikini Day.” The other Bikini Day is March 1, marking the date that the Japanese tuna fishing boat the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (in English, ‘Lucky Dragon No. 5’), based out of Shizuoka Prefecture, and other fishing boats were exposed to radiation from the aforementioned hydrogen bomb test.

The father of Roney Joel, 62, a pastor at a church on Ejit, was originally from Bikini. Stacked up in the kitchen of his house, which he called a “temporary residence,” were cans of tuna, instant ramen, and frozen chicken bought in Majuro.

There is a lack of fresh fruit on Ejit. The immigrants continue to simply rent land in Majuro and are unable to fish the waters freely. Roney Joel lived on Bikini for several years after a “declaration of safety” was issued by the United States in 1968. During that time he learned of the richness of life on the atoll, with its scattered islands forming an arch shape and its inland sea. “I want to go back. I don’t care about the radiation,” he remarked forlornly.

According to the Bikini Atoll local government with jurisdiction over the former residents and their descendants, nine of the 167 people of Bikini displaced in 1946 are still alive. Five of that total still live in the Marshall Islands, with the rest in the United States for medical reasons. Meanwhile, the results of a study published by a U.S. university in 2019 showed that high levels of radiation remain on Bikini Atoll. Due to concerns about contamination, the U.S. government has not taken any concrete steps to repatriate the residents back to their home islands.

People’s lives hit hard by financial difficulties

Bikinians struggle with their daily lives while longing for home and, to make matters worse, the Bikini Atoll local government finds itself in difficult financial straits. Jack Niedenthal, 66, who had just started work with the local government, revealed to me in his office that he was using his own computer and printer because the purchase of office equipment was out of reach for the government.

As of 2017, there were 59 million dollars remaining in a trust fund established with compensation money paid by the United States in recognition of the damage caused by the nuclear tests. Now, however, the fund amount is close to zero, in part due to the alleged improper use of funds by a former local government leader. Cash payouts to residents every three months have been reduced to 25 dollars per person, 20 percent of the previous amount. With prices as high as 3.50 dollars for a bag of carrots, for example, people’s living standards are hard hit.

The situation on the isolated island of Kili, where around 250 evacuees and their family members live, is particularly serious. According to Jamore Winkel, 45, who moved from Kili to Majuro, where he now works as a public servant, people on the island faced starvation over the course of last year. Mr. Winkel described how the situation on the island this year has improved with government intervention.

Before all else, the islands are surrounded by the rough waters of the Pacific Ocean, making it impossible for people to fish or for boats to deliver food and fuel in stormy weather. Has the history of suffering for the people of the islands been of benefit to humanity? “I really don’t know,” replied Mr. Jamore, shrugging off my question with a wry smile.

Keywords

Nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands

The United States conducted 67 nuclear tests on Bikini and Enewetak atolls in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958. In particular, the yield of the hydrogen bomb used in a test known as “Castle Bravo,” conducted on March 1, 1954, was around 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, resulting in fallout of large amounts of radioactive “ashes of death.” In addition to the residents of the atolls, crews of the Japanese tuna fishing boat the Daigo Fukuryu Maru and other fishing boats operating near the test site were all exposed to radiation. Aikichi Kuboyama, then a 40-year-old radio operator on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, died six months later.

(Originally published on March 13, 2024)