Questions from the Marshall Islands 70 years after Bikini Atoll disaster, Part 2: “Hibakusha”

Mar. 14, 2024

Decrease in number of people who can share experience, leading to sense of crisis in terms of passing on stories

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

“Afraid of the noise from the airplanes flying above, I was unable to move. I was taken to a U.S. base by American soldiers who had suddenly approached. Every day, I went into the sea to wash my body, as I was told to do.”

Exposure to “ashes of death”

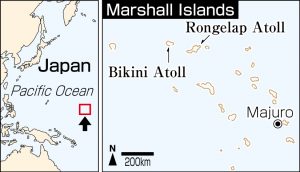

Kathy Joel, 75, who lives in Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, expressed her anger. “Americans looked down on us and did not care at all about the effects from radiation exposure.” On March 1, 1954, Ms. Joel, who was living on Rongelap Atoll at the time, was exposed to the radioactive “ashes of death” that fell as fallout after the “Castle Bravo” nuclear test the United States had conducted on Bikini Atoll. Later, as an adult, she suffered six miscarriages. She said she now takes medicine on a daily basis for a thyroid disorder.

On Rongelap, 86 people were exposed to radiation. Of that number, 13 are still alive and eight are now in the United States for family and other reasons.

Ms. Joel is one of the few who is able to share her experience with others. At the end of last month, in Majuro, she met with Setsuko Shimomoto, 73, a resident of Kochi City in Japan. Ms. Shimomoto is a surviving member of the family of a former crewmember from Kochi Prefecture who was exposed to the fallout on a fishing boat operating at the time near the atoll. Surrounded by members of the Japanese media, Ms. Joel shared her experience.

Also present was Mina Titus, 70, originally from Rongelap. At the time of the Castle Bravo test, Ms. Titus was a six-month-old infant. This writer also had the chance to speak with two people forced to move from their home of Bikini in 1946 but was unable to elicit detailed memories from them about the time of the testing.

Class for elementary and junior high-school students

People who experienced the nuclear disaster are now growing older, and their numbers are in decline. Meanwhile, even after the Marshall Islands won its independence from the United States in 1986, the nation continued to use American textbooks in its school system. With that, both children and today’s educators have not been taught about the nuclear devastation experienced by their own country. The government of the Marshall Islands, with a sense of crisis about passing on information about the nuclear disaster, established a so-called ‘nuclear committee’ in 2017 as one of the pillars of its activities, along with support for residents.

At the end of February, I visited a school in Majuro after hearing that the nuclear committee had developed a special class for elementary and junior high-school students. For the class, about 200 students in grades five to eight (in Japan, ranging from fifth grade of elementary school to second year of junior high school) had assembled in a gymnasium. At first, the atmosphere was casual, with children holding pieces of pizza or Japanese-style rice balls. But the audience fell silent when a video showing the devastation was played.

After the video, when an educator queried the students about how many times the United States had conducted nuclear tests, the first three responses were twice, 12 times, and five times. A fourth student, Setoki Qalubou, a seventh grader, arrived at the correct answer of 67 times. “I learned it here for the first time. I want to know more about what those who experienced the tests felt as they overcame sickness and hardship,” said Setoki.

Ahead of March 1, “Bikini Day,” a nearly week-long event was held in Majuro during which local and international students gave presentations about nuclear issues and exhibited related panels. Giff Johnson, 67, editor of the local newspaper The Marshall Islands Journal, sees such activities as a positive sign. He explained how “students had come to previous one-day events, quietly listened to speakers, and left.”

On the front page of the March 1 edition of the newspaper, Mr. Johnson summarized the students’ activities with a headline explaining how young people had dominated “nuclear week.” The facial expression of veteran journalist Mr. Johnson, who spoke of his “real concern” about the lack of understanding about nuclear issues among younger people, appeared to relax ever so slightly.

(Originally published on March 14, 2024)