Questions from the Marshall Islands 70 years after Bikini Atoll disaster, Part 3: Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

Mar. 15, 2024

Relief clauses might force nation to “clean up mess left by US”

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

At the end of February, a student debate was held at a university in Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, located in the central Pacific Ocean region. One student pronounced that ratifying the Treaty on the Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was a moral responsibility, given the suffering that has gone on for generations and the struggle against such negative effects. In response, a student argued that ratification would bring tension to the country’s alliance with the United States, a country under whose nuclear umbrella the Marshall Islands is situated. The theme of the debate was “Should the Marshall Islands ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)?” An audience of about fifty people listened attentively to the heated exchange between a proponent group and an opposition group, with each consisting of three students.

“Ratification difficult in reality”

The Marshall Islands’ history is marked by damage to its land and its people’s health from repeated U.S. nuclear tests. Meanwhile, the nation relies on the United States for its security and receives annual American financial aid amounting to the equivalent of around half of its government budget. Referring back to the debate, Tristen Zebedy-Horiuchi, 22, a university student who participated in the competition, said he hoped nuclear weapons would be eliminated from the world but that it would be difficult to make the decision to do so when considering the reality of the world today.

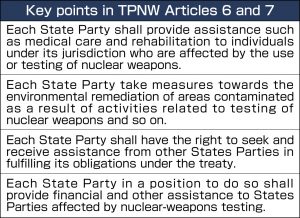

The view of Marshall Islands President Hilda Cathy Heine is clear. Ms. Heine has said that her nation would not able to ratify the treaty immediately. She shared that perspective in an interview with the media, including the Chugoku Shimbun, on March 4. She views as problematic the TPNW’s provisions that call on all treaty states parties to provide assistance to those that are affected by nuclear damage and to take measures for the environmental remediation of contaminated areas. She is concerned that if the Marshall Islands were to join the TPNW it might end up having to clean up the mess left by United States, despite the fact that the nation itself is the victim of such damage.

With respect to the issue of providing assistance to those affected, discussions are expected to begin this summer to determine the source of funding and methods for allocating the money, with the aim of establishing an international trust fund to serve as a financial resource. The Marshall Islands might benefit depending on how the system is arranged, which could ultimately influence the government’s decision on TPNW ratification.

On the other hand, the question of the possible U.S. response to ratification of the TPNW by the Marshall Islands was a point of concern for the students in the debate. For her part, the nation’s president replied in the interview that she would not take that issue into consideration when making the decision.

Interest among public stays flat

The nation originally took a strong stance vis-à-vis the United States. In a speech at a March 1 ceremony held in Majuro marking 70 years since the “Castle Bravo” nuclear test conducted on the Bikini Atoll, the president offered pointed criticism of a delay in U.S. Congressional approval for a bilateral agreement that would result in the provision of economic assistance to her nation. Ms. Heine spoke about how the United States had been a steadfast ally to her nation but also proclaimed that, “We cannot take that support for granted.” After the speech, she smiled and shook hands with the representative of the U.S. government who had been invited to the ceremony.

However, even more than diplomatic issues, something happened that made this writer feel that local interest in the treaty had waned. During the period from late February to early March, a delegation of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo) met with members of parliament and other leaders from the Marshall Islands. The delegation heard frequently from those with whom they spoke about how their own understanding of the treaty was inadequate.

Jess Gasper, Jr., 40, a parliamentary representative of Bikini Atoll, mentioned apologetically that he understood the treaty only superficially. Mr. Gasper had lived in the United States since he was five but returned home last year based on his desire to be of help in addressing economic issues faced by Bikini residents. With that sentiment, he ran for and won his first election.

Along with their children, some of the atoll’s former residents who had been forced to relocate from their homes because of the U.S. nuclear tests face struggles in their lives and even have difficulties with food security. Mr. Gasper said, “Nuclear weapons clearly provide no benefit to the world, and we are one representative example.” He is now busy working to prevent his citizens from starving. Indicating his desire to read and gain deeper understanding, he asked me to send him an email outlining the provisions of the TPNW.

(Originally published on March 15, 2024)