Survivors’ Stories: Yoshitsugu Tamaru, 85, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima City

Apr. 22, 2024

Horrific scenes, smells result in trauma

Hopes future generations do not experience same suffering

by Kana Kobayashi, Staff Writer

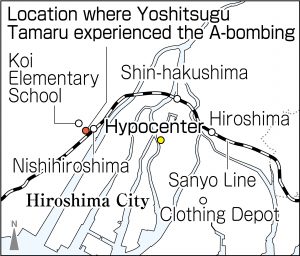

Nearly 79 years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Yoshitsugu Tamaru, 85, still cannot bring himself to visit two places. One is Koi Elementary School, located in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, and the other is the former Army Clothing Depot, in the city’s Minami Ward, which is a nationally designated important cultural property. The scenes he witnessed there remain as traumatic memories.

Mr. Tamaru was six years old and a first grader at Koi National School (present-day Koi Elementary School) at that time. He was living with his parents, grandparents, and a younger brother. On the morning of August 6, upon hearing the sound of an airplane, he and his father headed in the direction of Asahiyama Shrine, in Nishi Ward near their home, to see what was happening. He remembers that he had not yet left home for school. He momentarily left his father’s side to go to his aunt’s house in the neighborhood. At the front entranceway, he was hit by a bright flash and a loud boom.

When he returned home, his father was there with burns. Mr. Tamaru said, even though Asahiyama Shrine was located about three kilometers from the hypocenter, “He received burns probably because he had only been wearing undergarments at the time.” He added, “When I touched him, his skin peeled off.” He remembers his mother and grandmother tearing into pieces a yukata summer kimono and using the fabric as gauze for treating his father’s burns with oil used in cooking.

His cousin, a student at Yasuda Girls’ High School (present-day Yasuda Girls’ Junior and Senior High School), had not returned to his aunt’s house by August 7, the day after the bombing. Mr. Tamaru and his aunt walked to the Army Clothing Depot upon hearing that the wounded were being transported there. “The ground was so hot,” he said. The city still smoldered, and he could feel the heat in the soles of his feet through his straw sandals.

When arriving at the Clothing Depot, they heard the heart-rending cries of “Mom, help me.” They saw piles of what looked to be dead bodies. The depot building was filled with strong, indescribable smells. He found he had to sit down at the entrance. His cousin later returned home on her own.

The situation at Koi National School was also horrifying. The school was serving as a relief station for victims, and corpses were being thrown one after another into a pit dug in the schoolyard for incineration. He described how he had been filled with rage that “human beings were treated like that.” A dying woman grabbed him by the leg and begged for water, but he fled running away from her.

Soon after that, Mr. Tamaru fell ill. He suffered from vomiting that included blood as well as hair loss, which were considered to be acute symptoms. In addition, the memories of the Clothing Depot and the Koi National School remained as deep-seated trauma. It took all he had to attend school.

Thereafter, due to his father’s work, he attended junior high and high schools in Tokyo. Even as an adult, he was incapable of coming to terms with his A-bombing experience. However, the wish that his children’s generation should never experience the same suffering grew stronger within him.

He thought there must be something he could do. In 2009, after turning 70, he put his thoughts into action when he heard about and grew interested in the activities of the Hiroshima Peace Volunteers, who guide visitors around Peace Memorial Park, in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. After undergoing training, he began working as a volunteer.

Over the years, he experienced difficulties, including a landslide in Hiroshima in August 2014 from which he narrowly escaped death. But he maintained his sense of mission and persisted in his volunteer activities. “There are fewer and fewer people who experienced the atomic bombing,” he explained. He added, “I want generations that don’t know the horror of nuclear weapons to understand the reality.” He believes that both knowledge and imagination will serve to protect future generations.

(Originally published on April 22, 2024)