Thoughts from Hiroshima: POW camps and civilian internment camps, “negative legacy” also exists in Japan

Apr. 16, 2024

POW Research Network Japan publishes encyclopedia covering POW camps, civilian internment camps

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

During the Pacific theater of War World II, the former Japanese military’s abuse of prisoners of war (POW) in territories occupied by Japan has been depicted numerous times in movies. The history of Japanese-Americans being sent to internment camps in the United States is also widely known. However, how many people are aware that there were well over 100 POW camps and civilian internment camps in Japan? POW Research Network Japan, an organization engaged in research into the POW issue, has put together an encyclopedia that provides a comprehensive view of the situation. The publication uncovers heretofore unknown fragments of the story, challenging us to reflect on the significance of facing this past.

After the outbreak of the war, the former Japanese Imperial Army occupied an increasingly large area in the Asia-Pacific region. The Army took as POWs around 160,000 Allied soldiers, including those from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Some of the prisoners were sent to Japan to make up for labor shortages, and the roughly 36,000 POWs who made it alive to Japan were forced to work in shipyards or coal mines inside the country. About 10% of that number died from the wretched conditions they were forced to endure. Also interned were about 1,200 overseas residents of Japan that were nationals of an enemy country.

The 995-page publication is titled Horyoshuyojo minkanjin yokuryu-jo jiten—Nipponkokunai-hen (in English, ‘Encyclopedia of POW camps and civilian internment camps, Japan edition’; as seen in photo and published by Suirensha). The encyclopedia explains that history in its general overview and covers each of the 130 POW camps and 29 major internment camps that were located throughout Japan.

The camps existed for periods of from less than one month to three-and-a-half years. Most of the camps are not around today, and many are not even known by the people in each of the local areas.

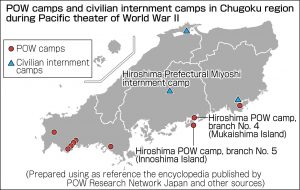

Using as clues a variety of documents, including materials from the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ), the group was able to identify camp locations, which are indicated on a map. The encyclopedia also explains the timeline of the camps’ opening and closing dates, the organizations managing the camps, and the numbers and nationalities of the POWs interned there. It provides detailed descriptions of what POW lives were like at the camps, as well as the number of those who died and the number that managed to return to their home countries. Also contained in the encyclopedia are supplementary historical materials, including relevant laws and regulations, giving readers an overall view of the situation.

The publication was written by 20 editorial committee members at the POW Research Network Japan, an organization formed in 2002 by citizens interested in the POW issue. Records of the situation are extremely scarce in Japan because many official documents were incinerated or lost after the country’s defeat in the war. With that, the organization has continued its work of surveying documents and memoirs of former POWs that exist overseas as well as conducting on-site surveys and interviews with the POWs. For public access, the group has uploaded the information it has been able to gather on its website. That was the impetus for a series of exchanges with former POWs and their families, which led to the gathering of even more information. The encyclopedia is a compilation of their efforts.

With respect to POW camps in the Chugoku region, which is made up of five prefectures including Hiroshima, the book contains information on camps located on the islands of Innoshima and Mukaishima in Onomichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture, six camps in Yamaguchi Prefecture, and one in Okayama Prefecture.

“The issue of POWs and internees might only represent a small fragment of the vast history of that war, but we should know how deep the wounds in how many people would be caused by war if it were to break out again,” said Taeko Sasamoto, 75, one of the editorial committee members as well as the co-representative and secretary-general of the group. Ms. Sasamoto, a resident of Yokohama City, showed this reporter around the Yokohama War Cemetery, the site that inspired her to engage in the research.

Countless grave markers are neatly lined up on a small hill. On them are inscribed the names and dates of deaths of soldiers representing the British Commonwealth. The soldiers hailed from the present-day United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, India, and other countries. Ms. Sasamoto, who once worked as a television script writer, gathered historical documents and researched the personal history of each of the individuals on her own. She said she came to understand that, “Even those who survived and made it back to their home country suffered physical and mental trauma and lived the post-war years with animosity toward Japan.” The same thing can happen today in Ukraine and the Palestinian-controlled Gaza, where the tragedy of war persists. “We must learn from the past. I hope the encyclopedia will help people exercise their imagination and put a stop to war,” proclaimed Ms. Sasamoto.

The encyclopedia also covers the internment of foreign residents in Japan who had lived as members of Japanese society but were declared “enemy aliens” because of the war.

Japanese people tend to focus only on the war with the United States, but, “This book reminds us of how many different foreigners were considered to be enemies by Japan because of the war,” said Mayumi Komiya, 72, a resident of Yokohama City who was one of the writers of the encyclopedia.

According to the detailed description of an internment camp in Miyoshi City in Hiroshima Prefecture, the camp held Belgian and American clergy in the early days and, later, crew members and medical personnel from a Dutch hospital ship that had been captured by the Japanese Navy. Ms. Komiya said she believes “this record of information will serve as a shared history among many people that will be passed on widely to others.”

According to the detailed description of an internment camp in Miyoshi City in Hiroshima Prefecture, the camp held Belgian and American clergy in the early days and, later, crew members and medical personnel from a Dutch hospital ship that had been captured by the Japanese Navy.

--------------------

Son traces hardships experienced on Innoshima Island by former British POW father, aged 103

In March, accompanied by his son and a friend, Duncan Lapsley, 65, a British national who lives in Australia, paid a visit to Innoshima Island in Onomichi City, relying on Koshi Kobayashi, 84, a member of the POW Research Network Japan and a resident of Fukuyama City. Mr. Duncan’s father, Robert Duncan, aged 103, was a POW at a camp on Innoshima Island but could not make the trip to Japan due to his advanced age.

Mr. Kobayashi showed the visitors the shipyard where the POWs worked, the site of the camp, and a temple where deceased POWs had been buried with care. The group also walked around the former site of a camp on Mukaishima Island, where local residents have erected a memorial plaque.

Because his father seldom speaks of his war experiences, Mr. Duncan said he has spent a long time trying to find out from him what he went through. Mr. Duncan said he wanted to know about the hardships his father endured as a young man, given that the experience must have greatly affected him later on.

Working with former POWs visiting Japan since the 1990s, Mr. Kobayashi has also guided former British soldiers who still harbor animosity toward Japan. However, when Mr. Kobayashi, paying heed to the history of the war, communicates with such individuals sincerely, “They come to understand that Japan is different from what it was during the war, and their hearts soften.” One of the former POWs told him how, after returning home from his visit to Japan, he no longer suffered nightmares of being chased by Japanese soldiers.

In recent years, the children and grandchildren of former POWs visit Mr. Kobayashi. “They are trying to learn about their fathers’ and grandfathers’ experiences and pass that information on,” he said. “It is hard to face that negative history, but Japanese people also need to reflect on it,” added Mr. Kobayashi.

(Originally published on April 16, 2024)