Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, unfinished judgment, Part 7: Forced to make decision on which country, U.S. or Japan, to take to court

Apr. 29, 2024

In mid-1954, attorney Shoichi Okamoto had hit a wall. His lawsuit seeking compensation for damages from the United States based on the claim that the atomic bombings were a violation of international law had been reacted to negatively even by Americans considered to be passionate about the protection of human rights. The reasons included that the lawsuit would harm Japan-U.S. relations and that there were no legal grounds for the action.

Investigating responsibility with colleague

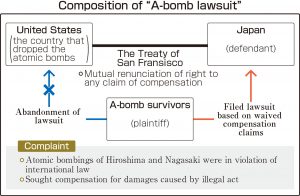

Mr. Okamoto argued that the Treaty of San Francisco — which had come into effect in 1952 and stipulated that Japan would renunciate its right to claim compensation from the United States for damages arising from the war — should be invalid from the standpoint of the human rights of survivors. Together with a colleague, Mr. Okamoto then started looking into the responsibility of the Japanese government, which had accepted the treaty, regarding compensation for A-bomb survivors.

The colleague was Yasuhiro Matsui, an attorney still in his early 30’s who died in 2008 at the age of 85. In 1953, three years after becoming a lawyer in Tokyo, Mr. Matsui learned about Mr. Okamoto’s idea and offered his cooperation.

Mr. Okamoto was born on Sagishima Island, part of present-day Mihara City in Hiroshima Prefecture. Because he could not afford the costs of higher education, he moved to Osaka at the age of 14, where he attended night school while working at a hardware store. Afterward, he started work at a law office and continued his studies at night.

In 1943, after studying under those trying conditions, he made it into Kansai University. However, he was immediately drafted into the military’s student corps and assigned to an Army unit in Hiroshima. He was in China when the war ended. His younger brother, who had been in Hiroshima City, was wounded in the atomic bombing and his relatives were killed. During the process of demobilization after the war, Mr. Matsui witnessed the devastation of Hiroshima.

In his book titled Senso to Kokusaiho (in English, ‘War and international law’), published in 1968, he wrote about how in our daily lives, for example, stealing is punishable by law, and he posed the following questions about the dropping of the atomic bombs.

“Will such a large-scale atrocity be allowed to go unpunished as a crime? If so, will people who suffered or who are now suffering the torments of hell be offered help?”

Aiming to provide relief to victims

As a result of their investigation, Mr. Matsui and Mr. Okamoto determined that they would be able to file a lawsuit in a Japanese court seeking damages against the Japanese government, which had waived its rights to claim compensation from the United States, on the grounds that the dropping of the atomic bombs violated international law. Encouraged by the movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs that was spreading throughout Japan in the wake of the Lucky Dragon No. 5 crew’s exposure to radiation from the U.S. hydrogen bomb test conducted on Bikini Atoll in March 1954, they proceeded with preparations for filing a lawsuit. Through the lawsuit, they aimed to pave the way for banning atomic and hydrogen bombs and providing relief to victims.

The legal petition was prepared by Mr. Okamoto. Using a term that indicated indiscriminate mass murder, the petition emphasized the illegality of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It sought damages of between 200,000 and 300,000 yen per plaintiff from the Japanese government, which had waived the right to claim compensation from the United States.

The petition stated, “If the extensive destructive power of the blast and thermal rays as well as the atrocity resulting from the particularly harmful impact of more extensive radiation on the human body were to be recognized, the dropping of the atomic bombs should be considered an act of mass murder against humanity.”

The petition was filed with the Tokyo District Court and the Osaka District Court in April 1955. A total of five A-bomb survivors were named as plaintiffs. Among them was Mr. Shimoda, whose name would later be etched into the annals of the history of international law.

(Originally published on April 29, 2024)