Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, unfinished judgment, Part 9: A-bombed Japan at court

May 1, 2024

Development of argument in support of atomic bombings

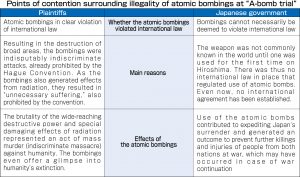

October 1955 marked the passage of six months since lawsuits for the “A-bomb trial” were filed at the Tokyo and Osaka district courts (the two cases were later merged and handled in Tokyo), in which five plaintiffs affected by the atomic bombing claimed that the bombings had violated international law and sought compensation from the Japanese government, which had waived its right to demand compensation from the United States. That month, the national government filed a written response at the court that called for rejection of the plaintiffs’ claims.

The government emphasized it “cannot immediately be concluded that they (the atomic bombings) were illegal.” For that reason, it argued that the rights claimed by the plaintiffs were not included in any right to demand war-related compensation from the U.S., which Japan had waived when it signed the Treaty of San Francisco, and thus invalidated the plaintiffs’ claim.

Yasuhiro Matsui, an attorney for the plaintiffs, recalled the government’s response in his book, writing that he “could not help but feel resentment.” Due to the complexity of the case, it took more than four years for the preparatory procedures, during which the arguments from both sides were summarized, with six preparatory documents submitted by the plaintiff and four by the Japanese government. The government continued to make claims that were closer to the U.S. side than the side of the victims.

Regulations on new weapon were point of dispute

The biggest point of contention was the fact that the atomic bombs represented a new weapon.

The government’s argument involved the idea that the atomic bombings were legal because no international law had been in place directly banning use of the weapons since they represented a new type of weapon. Its claim also asserted that no such international law had been established at the time of the trial. The government’s argument was similar to the logic of the U.S. Army, which explained at around the same time that use of nuclear weapons was deemed to be legal in its combat manual.

Meanwhile, the plaintiffs insisted the bombings should be considered illegal based on the fundamental principle of existing international law. The Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land (the Hague Convention) had already prohibited indiscriminate attacks on cities where military and non-military targets needed to be distinguished. In reality, four days after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the government had made a formal protest to the United States, in which it had argued that the attacks were a violation of international law based on that very convention.

When the plaintiffs pointed out the inconsistency in the government’s stance, the defendant explained that it was due to its change of view after it no longer had the standing of belligerent nation. The government even laid out a case in support of the atomic bombings. “Use of the atomic bombs contributed to expediting Japan’s surrender and generated an outcome to prevent further killings and injuries of people from both nations at war, which may have occurred in case of war continuation,” as was excerpted from the preparatory documents dated June 27, 1958.

Inhumane nature of bombings expressed

In the initial phase of the preparatory proceedings, held a total of 27 times, Shoichi Okamoto, an attorney from Osaka who was a proponent of the lawsuit, traveled to Tokyo to attend the proceedings held at the Tokyo District Court. However, as his health deteriorated, Mr. Okamato had no choice but to stay at home to recover.

From Tokyo, Mr. Matsui sent every draft of the preparatory documents to Mr. Okamoto by mail and sought his advice. Mr. Okamoto focused on detailed wordings in the documents that described the inhumanity of the atomic bombings. In a reply letter, which remains today, he suggested revision of the phrase “immense destructive power” in the draft to “ultra-cruel mass murder,” deeming the original phrasing to be “somewhat weak.”

In April 1958, three years after the lawsuit was filed, Mr. Okamoto died from a brain hemorrhage. He was 66. Mr. Matsui, in his 30’s, took on Mr. Okamoto’s objectives and continued his work at court.

(Originally published on May 1, 2024)