Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, unfinished judgment, Part 8: Shimoda case

Apr. 30, 2024

One plaintiff lost 12 family members in atomic bombing

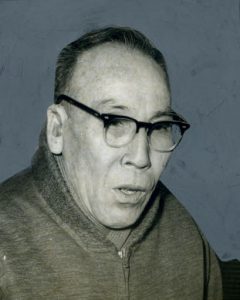

The “A-bomb trial” involved five plaintiffs affected by the atomic bombing who claimed that the bombing had violated international law and sought compensation from the Japanese government, which had waived its right to demand compensation from the United States. Overseas, the trial is known as the “Shimoda case.” The origin of the name comes from Ryuichi Shimoda, listed as the first plaintiff in the complaint submitted to the Tokyo district court in April 1955, who died in 1964 at the age of 65.

No remains of family found

Few materials including records of testimonies from the trial remain today. However, a detailed description of his experience in the atomic bombing that Mr. Shimoda gave to the Hawaii Times, a Japanese language newspaper, on his visit to relatives living in Hawaii in the United States appeared in the newspaper’s March 22, 1962 edition.

Mr. Shimoda was born to a Japanese immigrant family in Hawaii in 1898. At the age of 23, after working in the sugar fields there, he traveled to Hiroshima, his parents’ hometown. He married and had eight children, and his family lived in the Nakahiro-machi district (in the city’s present-day Nishi Ward).

On August 6, 1945, he was just outside his house. He was 47 at the time. He said, “I saw a sudden flash in the sky. Then, at almost the same time, I felt a searing heat on my right arm, which I had been holding above my head.” He helped his wife, who was crying out, from inside the collapsed house.

Despite searching for them, he was unable to find even the remains of five of his children who were out of the house at the time of the bombing.

His third son, Kiyoshi, 12 at the time, had left home to return a large cart Mr. Shimoda had borrowed from a friend. His second daughter, Yuriko, 10; his third daughter, Kazue, who was seven; and his fourth daughter, Toshiko, four, had all been on the cart, as they had all hoped to ride it on the way. Reiko, his oldest daughter who was 16, also never returned after leaving for work that day.

“Cannot work”

The plaintiffs’ petition included the description of Mr. Shimoda’s dire economic situation and his reliance on remittances from his older sister in Hawaii. The complaint reads, “Mr. Shimoda cannot work due to the keloids that stretch from the right side of his belly to the left side of his back and become infected around spring every year, along with kidney and liver damage.”

His younger brother’s entire family of seven were also killed in the bombing. He had placed memorial tablets for 12 of his deceased family members on the Buddhist altar at his home and lived in the hopes that, “No one anywhere in the world should ever suffer what we have,” as described in the Hawaii Times article.

Mr. Shimoda joined the group of plaintiffs for the lawsuit through the Hiroshima City Atomic Bomb Survivors Association. Maki Tada, a resident of Hiroshima City who died in 1985 at the age of 78, also participated in the trial through the association. She had suffered serious injuries at her location of slightly more than two kilometers from the hypocenter at the time of the bombing, with keloids remaining on her shoulders and arms. She earned a living by working in construction in an unemployment relief project carried out by the Hiroshima City government, while raising her three children.

The other three plaintiffs comprised one person each from Tokyo, Osaka, and Hyogo Prefecture. One, Toshitsugu Hamabe from Tokyo, had lost his wife and four daughters in the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

The complaint concluded, “We hope for a hearing that seeks a higher law and the truth about the atomic bombings.” About six months after the complaint was submitted to the court, the Japanese government, the defendant in the lawsuit, provided a written response that directly disputed the plaintiffs’ claims.

(Originally published on April 30, 2024)