Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Chugoku Shinbun and the press code – Diving into the materials, Part 1: Eliminating militaristic propaganda

Jul. 22, 2024

by Kazuo Yabui, Visiting Senior Staff Writer

The General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ), which advanced into Japan after that country’s defeat in the war, issued a press code (set of media guidelines) based upon which censorship was implemented for the monitoring of media and cultural activities as part of “postwar reforms.” Our first series involving the press code reviewed the censorship of articles with A-bombing content published by the Chugoku Shinbun. The main scope of this second series involves articles not related to the atomic bombings. The reality of the censorship will be interpreted based on remaining materials, including from the Yukan Hiroshima, a local evening newspaper published by an affiliated company of the Chugoku Shimbun. For this series, we received cooperation from Luli van der Does, associate professor at the Hiroshima University Center for Peace who specializes in memory studies, social psychology, and discursive analysis, in examining the materials.

On November 20, 1946, the Yukan Hiroshima ran an article with the headline “Story of the return home of living ‘Eirei’: Loss in war unbelievable, staff at concentration camp very kind.”

The article told the story of a Japanese man’s experience of being captured by the U.S. military and held as a prisoner of war (POW). In 1943, a ship requisitioned by the former Japanese Imperial Navy was attacked and sunk by a U.S. submarine on the way to Wake Island in the central Pacific Ocean. Of the 11 crew members on board, one survived and became a POW. The article reported that the prisoner had stayed in concentration camps in the U.S. states of Wisconsin and Hawaii, returning to Japan after it had lost the war.

“Eirei” considered violation of press code

The contents of the article were acceptable, but the term “Eirei,” which had been incorporated into the headline, did not pass censorship.

The press code was first issued in September 1945. Censorship guidelines used at that time spelled out that “Senshi-sha” or “Senbotsu-sha” (in English, variations on the term ‘the war dead’) “may be substituted” for the phrase “Eirei.” In the guidelines, GHQ avoided use of the stronger expression “should be used” because it wanted to prioritize the principle of offering “suggestions” to media organizations rather than forcing them to use certain language.

Why was the word “Eirei” not considered acceptable? Use of that expression was thought to glorify the war dead.

Teruo Ariyama, former professor at Tokyo Keizai University who specializes in media history, published a book titled “Modern Japanese Media History II,” in which he wrote, “The GHQ was focused on prohibiting ‘dissemination of past ideology based on militarism and ultra nationalism,’ as a key element of general policies during the initial phase of the occupation. Obviously, censorship placed an emphasis on the elimination of ‘militaristic, ultra-nationalistic ideology.’”

Newspaper accepted GHQ directive

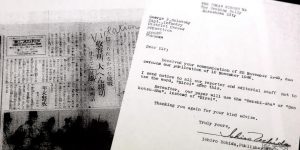

The Yukan Hiroshima sent GHQ a reply signed by its chief editor, Ichiro Uchida, after it had been informed that the article violated the press code. In fact, few documents remain that reveal how the newspaper dealt with the GHQ directive.

In the newspaper’s response was the phrasing, “I send notice to all our reporter and editorial staff not to use the word, ‘Eirei’ after this. Hereafter, our paper will use the ‘Senshi-sha’ or ‘Senbotsu-sha’ instead of ‘Eirei’.” The response indicated that the newspaper would faithfully adhere to the GHQ directive.

In addition to media organizations such as newspapers and radio broadcasters, other subjects of censorship were the movie industry, theatrical acts, kabuki plays, manzai acts (stand-up comedy), Naniwabushi music (ballads based in the Osaka area), and even picture-story shows.

An article involving kabuki performances published in the Yukan Hiroshima on August 21, 1946, was also censored.

The article’s headline read, “Kabuki plays like Chushin-gura and Sendai-Hagi have been banned.” The article reported that the GHQ’s cinema and theatrical performance censorship office in Osaka had announced the banning of the performances of 234 works, consisting of 19 kabuki plays and 215 modern dramas by the end of July that year.

The ban on public performances reflected the judgment of the GHQ’s Information Distribution Section (IDS), which had concluded that kabuki plays had no place in the modern world because they were based on feudal loyalty and a belief in the principle of revenge.

Keywords

Yukan Hiroshima

An affiliated company of the Chugoku Shimbun, the Yukan Hiroshima began to publish its local evening newspaper on June 1, 1946. The newspaper’s focus was mainly local news, and at one time it attained a circulation of more than 50,000. The newspaper’s name was changed two times, to the Yukan Chugoku and the Yukan Chugoku Shimbun. On October 1, 1952, the newspaper ceased publication because the Chugoku Shimbun had begun to sell both morning and evening papers.

(Originally published on July 2, 2024)

The General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ), which advanced into Japan after that country’s defeat in the war, issued a press code (set of media guidelines) based upon which censorship was implemented for the monitoring of media and cultural activities as part of “postwar reforms.” Our first series involving the press code reviewed the censorship of articles with A-bombing content published by the Chugoku Shinbun. The main scope of this second series involves articles not related to the atomic bombings. The reality of the censorship will be interpreted based on remaining materials, including from the Yukan Hiroshima, a local evening newspaper published by an affiliated company of the Chugoku Shimbun. For this series, we received cooperation from Luli van der Does, associate professor at the Hiroshima University Center for Peace who specializes in memory studies, social psychology, and discursive analysis, in examining the materials.

On November 20, 1946, the Yukan Hiroshima ran an article with the headline “Story of the return home of living ‘Eirei’: Loss in war unbelievable, staff at concentration camp very kind.”

The article told the story of a Japanese man’s experience of being captured by the U.S. military and held as a prisoner of war (POW). In 1943, a ship requisitioned by the former Japanese Imperial Navy was attacked and sunk by a U.S. submarine on the way to Wake Island in the central Pacific Ocean. Of the 11 crew members on board, one survived and became a POW. The article reported that the prisoner had stayed in concentration camps in the U.S. states of Wisconsin and Hawaii, returning to Japan after it had lost the war.

“Eirei” considered violation of press code

The contents of the article were acceptable, but the term “Eirei,” which had been incorporated into the headline, did not pass censorship.

The press code was first issued in September 1945. Censorship guidelines used at that time spelled out that “Senshi-sha” or “Senbotsu-sha” (in English, variations on the term ‘the war dead’) “may be substituted” for the phrase “Eirei.” In the guidelines, GHQ avoided use of the stronger expression “should be used” because it wanted to prioritize the principle of offering “suggestions” to media organizations rather than forcing them to use certain language.

Why was the word “Eirei” not considered acceptable? Use of that expression was thought to glorify the war dead.

Teruo Ariyama, former professor at Tokyo Keizai University who specializes in media history, published a book titled “Modern Japanese Media History II,” in which he wrote, “The GHQ was focused on prohibiting ‘dissemination of past ideology based on militarism and ultra nationalism,’ as a key element of general policies during the initial phase of the occupation. Obviously, censorship placed an emphasis on the elimination of ‘militaristic, ultra-nationalistic ideology.’”

Newspaper accepted GHQ directive

The Yukan Hiroshima sent GHQ a reply signed by its chief editor, Ichiro Uchida, after it had been informed that the article violated the press code. In fact, few documents remain that reveal how the newspaper dealt with the GHQ directive.

In the newspaper’s response was the phrasing, “I send notice to all our reporter and editorial staff not to use the word, ‘Eirei’ after this. Hereafter, our paper will use the ‘Senshi-sha’ or ‘Senbotsu-sha’ instead of ‘Eirei’.” The response indicated that the newspaper would faithfully adhere to the GHQ directive.

In addition to media organizations such as newspapers and radio broadcasters, other subjects of censorship were the movie industry, theatrical acts, kabuki plays, manzai acts (stand-up comedy), Naniwabushi music (ballads based in the Osaka area), and even picture-story shows.

An article involving kabuki performances published in the Yukan Hiroshima on August 21, 1946, was also censored.

The article’s headline read, “Kabuki plays like Chushin-gura and Sendai-Hagi have been banned.” The article reported that the GHQ’s cinema and theatrical performance censorship office in Osaka had announced the banning of the performances of 234 works, consisting of 19 kabuki plays and 215 modern dramas by the end of July that year.

The ban on public performances reflected the judgment of the GHQ’s Information Distribution Section (IDS), which had concluded that kabuki plays had no place in the modern world because they were based on feudal loyalty and a belief in the principle of revenge.

Keywords

Yukan Hiroshima

An affiliated company of the Chugoku Shimbun, the Yukan Hiroshima began to publish its local evening newspaper on June 1, 1946. The newspaper’s focus was mainly local news, and at one time it attained a circulation of more than 50,000. The newspaper’s name was changed two times, to the Yukan Chugoku and the Yukan Chugoku Shimbun. On October 1, 1952, the newspaper ceased publication because the Chugoku Shimbun had begun to sell both morning and evening papers.

(Originally published on July 2, 2024)