Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Chugoku Shimbun and the press code — Diving into the materials, Part 3: Readers’ sentiments kept locked away

Jul. 5, 2024

After the war ended, numerous challenges arose with Japan’s defeat in the war. One was how to repatriate back to Japan the people remaining overseas, including soldiers and other military personnel as well as people who had emigrated to other countries.

A reader's call that illustrated one aspect of that issue was published in the Chugoku Shimbun's letter-to-the-editor column “Meikyou” on December 1, 1945,.

“Rescue our compatriots overseas”

The heading of the letter to the editor written by a man in Hiroshima was “Rescue our compatriots overseas.” He welcomed the fact that the newspaper had recently begun to carry articles calling for assistance for Japanese people who remained outside of Japan. Seeking increased protection for such nationals, the man argued in his letter that more than a few Japanese people waiting to return from the Korean Peninsula were dying, suffering from hunger and severely cold weather.

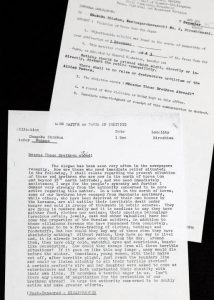

The letter likely represented the candid feelings of the Japanese people at that time. However, the General Headquarter of the Allied Forces (GHQ) deemed the letter to be in violation of its press code. Of the 10 criteria listed in the press code, the GHQ concluded that the letter had violated the second article, which indicated “Nothing shall be printed which might, directly or by inference, disturb the public tranquility,” as well as the third, which read, “There shall be no false or destructive criticism of the Allied Powers.”

A readers’ column in the Yukan Hiroshima newspaper titled “Machi-no-koe” (in English, ‘Voices in the street’), published nearly a year after the end of the war on September 8, 1946, carried another reader’s letter to the editor, which was also “Disapproved” for its violation of the press code.

The letter was sent from a woman living in the area of Kaitaichi-cho, Aki-gun (present-day Kaita-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture) under the heading “Repatriate the officers and soldiers outside of Japan.” She wrote that “I am waiting for my son, who was serving in the conflict in Manchuria [now part of the Northeast region of China].” She described how she eagerly awaited her son’s return to Japan. “I have hardly slept at night since May,” when the withdrawal began, she wrote.

In the letter, one part was underlined and the word “Violation” added in pencil. It was a section in which she expressed her hope for the organization of a prefectural association to promote the withdrawal of soldiers and compatriots, after she learned of the establishment of similar associations in other areas of Japan from a radio program. The reason behind the violation decision was because the letter had made reference to the “Ma [MacArthur] general headquarters (GHQ).”

Letters seen as disturbing public

Two days after the letter to the editor was carried in the newspaper, a letter from another woman calling herself “A mother of a soldier killed in the war” appeared in the column as a response to the first letter.

The response read, “I feel envy and agony in my heart when I see soldiers having fun with their families upon their return after peace was achieved by Japan’s defeat in the war.” It added, “I understand very well that parents of soldiers who have yet to return to Japan are desperately waiting for their sons to return… but I am overwhelmed by indescribable discomfort when they express their own wishes in such a straightforward manner in words.”

In that way, the woman, who was once called “a mother of the militaristic nation,” disclosed her unbearable emotions. The full text of the letter, consisting of 40 lines, was underlined in the censorship process and “Disapproved” due to violation of the press code’s second article.

While living amid chaos after the war, some naturally expressed their hopes for their family or compatriots overseas to return to Japan safely or shared the agony from having lost a soldier son in the war. But from the perspective of the GHQ’s occupation policy, those sentiments were merely seen as something that could “disturb the public tranquility.”

(Originally published on July 5, 2024)

A reader's call that illustrated one aspect of that issue was published in the Chugoku Shimbun's letter-to-the-editor column “Meikyou” on December 1, 1945,.

“Rescue our compatriots overseas”

The heading of the letter to the editor written by a man in Hiroshima was “Rescue our compatriots overseas.” He welcomed the fact that the newspaper had recently begun to carry articles calling for assistance for Japanese people who remained outside of Japan. Seeking increased protection for such nationals, the man argued in his letter that more than a few Japanese people waiting to return from the Korean Peninsula were dying, suffering from hunger and severely cold weather.

The letter likely represented the candid feelings of the Japanese people at that time. However, the General Headquarter of the Allied Forces (GHQ) deemed the letter to be in violation of its press code. Of the 10 criteria listed in the press code, the GHQ concluded that the letter had violated the second article, which indicated “Nothing shall be printed which might, directly or by inference, disturb the public tranquility,” as well as the third, which read, “There shall be no false or destructive criticism of the Allied Powers.”

A readers’ column in the Yukan Hiroshima newspaper titled “Machi-no-koe” (in English, ‘Voices in the street’), published nearly a year after the end of the war on September 8, 1946, carried another reader’s letter to the editor, which was also “Disapproved” for its violation of the press code.

The letter was sent from a woman living in the area of Kaitaichi-cho, Aki-gun (present-day Kaita-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture) under the heading “Repatriate the officers and soldiers outside of Japan.” She wrote that “I am waiting for my son, who was serving in the conflict in Manchuria [now part of the Northeast region of China].” She described how she eagerly awaited her son’s return to Japan. “I have hardly slept at night since May,” when the withdrawal began, she wrote.

In the letter, one part was underlined and the word “Violation” added in pencil. It was a section in which she expressed her hope for the organization of a prefectural association to promote the withdrawal of soldiers and compatriots, after she learned of the establishment of similar associations in other areas of Japan from a radio program. The reason behind the violation decision was because the letter had made reference to the “Ma [MacArthur] general headquarters (GHQ).”

Letters seen as disturbing public

Two days after the letter to the editor was carried in the newspaper, a letter from another woman calling herself “A mother of a soldier killed in the war” appeared in the column as a response to the first letter.

The response read, “I feel envy and agony in my heart when I see soldiers having fun with their families upon their return after peace was achieved by Japan’s defeat in the war.” It added, “I understand very well that parents of soldiers who have yet to return to Japan are desperately waiting for their sons to return… but I am overwhelmed by indescribable discomfort when they express their own wishes in such a straightforward manner in words.”

In that way, the woman, who was once called “a mother of the militaristic nation,” disclosed her unbearable emotions. The full text of the letter, consisting of 40 lines, was underlined in the censorship process and “Disapproved” due to violation of the press code’s second article.

While living amid chaos after the war, some naturally expressed their hopes for their family or compatriots overseas to return to Japan safely or shared the agony from having lost a soldier son in the war. But from the perspective of the GHQ’s occupation policy, those sentiments were merely seen as something that could “disturb the public tranquility.”

(Originally published on July 5, 2024)