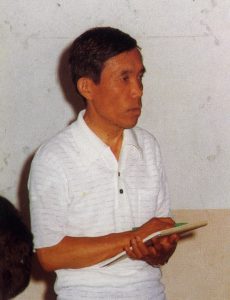

My Life — Interview with Hiromu Morishita (1930–), A-bomb survivor and teacher, Part 11: Peace education

May 4, 2022

Worked hard to prepare teaching materials and conduct survey

I brought back some homework from the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Pilgrimage. At that time, the civil rights movement in the United States was very active. A local teacher told me that their textbooks contained few descriptions of the issue of racism against Black people, and asked me whether the textbooks of the A-bombed country of Japan included details about the atomic bombings. I ended up nodding my head in an ambiguous way. But I doubted my own answer and, after returning to Japan, started to look into the issue.

Carrying a camera and a tripod to publishing companies in Tokyo, I asked them to allow me to photograph the contents of textbooks of not only social studies and history, but all subjects, ranging from Japanese language to music. The results showed that the number of descriptions about the damage caused by the atomic bombings was less than I had expected. That was not good enough. I therefore decided to create supplementary reading materials, on which I began to work with my colleagues.

In 1971, Hiromu Morishita published a collection of teaching materials for peace education. In addition, in 1974, his group also published a supplementary reading material titled “Asu ni Ikiru” [in English, ‘Living for tomorrow’].

The supplementary reading material was widely used, and we ended up publishing 13 editions. In addition to the atomic bombings, the material also covered war history and security issues. To incorporate the Battle of Okinawa, I visited Okinawa to study the issue on my own. A sequel that included sections on environmental issues and economic disparity was published in 1992.

He devoted himself to one more thing in his school. That was a survey of the consciousness of high school students.

In 1963, I started a survey to grasp how much high school students who were born after the war knew about the atomic bombings and what they thought about them. To prevent the survey from becoming sloppy, I studied psychological survey methods and paid careful consideration to the survey questions. More and more people cooperated in the survey work, and starting in 1971, the Hiroshima High School Staff Union (in Japanese, ‘Kokyoso’) conducted the survey. The survey helped to reflect the student attitudes in education.

I then analyzed data that had been collected over the course of 15 years of the survey until 1985. I was able to confirm that the students had come to understand the anger directed at the atomic bombings and the damage caused and that there was a growing sense of crisis around the issue of nuclear war. I believe that the contents and tone of peace education have changed. As time has passed, memories of the atomic bombings have faded and the political situation has shifted. Now, there are no teachers who experienced the war and only a handful of students with the desire to learn about that time. Despite that situation, we need to continue our efforts in peace education.

With no direct experience, it is only natural that they have no sense of the reality. However, for our future, it is important to try to learn about the tragedy of war and think about how to prevent it. I also served as the first president of the A-bombed Teachers Association of the Hiroshima Prefectural High School Staff Union. One time, over a loudspeaker used by a political campaign vehicle, a voice shouted out, “There is a communist teacher at this school.” Despite that, my determination to put emphasis on peace education was not at all shaken.

(Originally published on May 4, 2022)