Ishii of Akitakata donates younger sister’s belongings to Peace Memorial Museum

Aug. 5, 2024

Sister dreaming of becoming midwife, killed in atomic bombing

Ishii donated draft of application for admission and embroidery tools, hoping they will be put to “good use for the future”

by Kana Kobayashi, Staff Writer

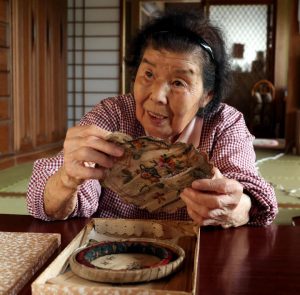

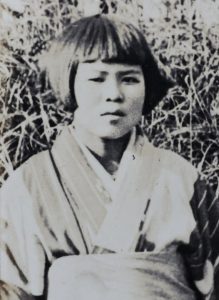

Mihoka Ishii, 95, an A-bomb survivor living in Akitakata City in Hiroshima Prefecture, lost her younger sister Sayoko Uchida, then 14, in the atomic bombing. Sayoko was studying to become a midwife in Hiroshima. For a long time, Ms. Ishii has carefully kept a letter Sayoko wrote to her family and other things left by her. But this summer she decided to donate them to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. She earnestly hopes people will never forget there were girls whose dreams were dashed by the atomic bombing.

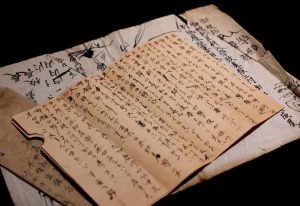

Ms. Ishii picked up each of her beloved sister’s belongings, thinking of her sister with fondness: The letter Sayoko wrote to her family in her immature handwriting, the drafts of her application to enter midwifery school written with a brush, the embroidery tools she always used, and her works with a variety of stitches. “She was good-natured, determined and hardworking in everything she did,” said Ms. Ishii.

At that time, Ms. Ishii lived with her family on Nomi Island (now part of the city of Etajima). She was the third daughter among the seven children. Sayoko, two years younger than Ms. Ishii, was her immediate younger sister and they got along well. After completing the advanced course at a local national school on Nomi Island, Sayoko stayed with her aunt in Hiroshima’s Showa-machi (now part of Naka Ward) and worked at an ophthalmologic clinic in Ote-machi (now part of Naka Ward), while learning midwifery at a school.

Hoping to work in the former Manchuria (northeastern China), Sayoko often told her family that she would become a midwife and go to Manchuria. In a letter to her family dated June 20, 1945, she wrote about how she commuted from her workplace to school and begged her parents to buy her a book on midwifery.

But her dream was shattered in an instant. On her way to work on August 6, Sayoko was exposed to the atomic bomb on a street about one kilometer from the hypocenter. She suffered severe burns all over her body.

At that time, Ms. Ishii was on Nomi Island and heard the explosion from the direction of Hiroshima. She was worried about her sister’s safety. She soon learned from an acquaintance that Sayoko was admitted to an army hospital in the present-day Minami Ward. On the following day, August 7, she went to Hiroshima, where there were still some fires, and was exposed to residual radiation.

Ms. Ishii found Sayoko at the hospital. “Sayoko’s hair had been burned, her face and arms were swollen, and her skin was peeling off,” said Ms. Ishii. She did not recognize Sayoko at first glance and had to ask, “Are you really Sayoko?”

Ms. Ishii managed to help her onto a boat and brought her back to her home on Nomi Island. But the only treatment the family could provide was to put grated cucumbers or potatoes on a cloth and cover the burnt skin with it. “It must have been painful, but she never complained.” However, Sayoko passed away on August 19 despite all the care taken of her.

“Such a sad thing must not happen to young people and children who have bright prospects,” said Ms. Ishii. Every time she comes across news of the ongoing wars in Ukraine, Gaza in the Palestinian autonomous territories and elsewhere, she recalls the devastation caused by the atomic bombing and is filled with sadness. She strongly hopes her sister’s belongings will be utilized for the future.

(Originally published on August 5, 2024)