Memories engraved in A-bombed buildings, Part 4: Honkawa Elementary School

Jul. 24, 2024

Painful memories at school, to which she gave up on return

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

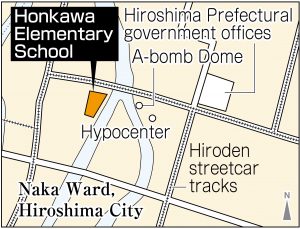

Honkawa National School (present-day Honkawa Elementary School), in Hiroshima City, was the school closest to the hypocenter. Baek Nyeonsun, 88, a third-grade student at the time of the bombing who now lives in the city’s Naka Ward, said of her school life, “I have no happy memories.” After the war, she gave up on returning to school because she had to work, and she struggles with writing even now.

She was born to parents who came to Hiroshima City from the Korean peninsula. Before the atomic bombing, she lived in the area of Sorazaya-cho (now part of the city’s Naka Ward) with the other six members of her family. She recalls, “I would often go to a doctor’s office and a movie theater in Nakajima-honmachi. I used to take naps on the grounds of the Sorasaya Inari Shrine.”

At Honkawa National School, however, she was verbally bullied. “You’re just a Korean,” she was told. At that time, “I considered Korea to be a foreign country, so I didn’t understand why I was being bullied.” She remembers her mother frequently visiting the school to protest her daughter’s mistreatment.

She did not participate in the mass evacuation for students in the third grade and older. On August 6, 1945, she and her family experienced the atomic bombing. In her Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, issued under her Japanese name “Sumiko Shirakawa,” is written “Sorazaya-cho: 0.7 km,” the location at which she experienced the bombing. “I didn’t feel any light or sound,” she said. The only student who survived the atomic bombing at the school was the sixth-grade student Kiyoko Imori, who died in 2016 at the age of 82.

Ended up working herself

Holding on tightly to the work pants worn by her mother, who told her, “Don’t look around,” Ms. Baek and her mother fled to a relative’s house in the area of Eba in Hiroshima. She still remembers her uncle welcoming her and her mother with tears in his eyes, saying, “I can’t believe you managed to survive.” All of her family members were safe. But soon after the atomic bombing, her father fell ill. The family could not return to the Korean peninsula due to the post-war turmoil. To allow her younger brothers and sisters to go to school, Ms. Baek started working.

Ms. Baek would leave Eba before dawn, walk to Hiroshima Station, and take an early morning train to Miyoshi. Her job was to bring back rice she could obtain on the black market. Some days she would make two round trips. She slept only a few hours a day and learned to read Japanese from train station signs and magazines. She recalled, “I made sweet potato candy and worked at a cider factory. I did whatever I could.”

When she was 16, she wed a man from the Korean peninsula in a marriage arranged through a go-between. She worked hard by doing, for example, construction work that was part of the city’s relief work for the unemployed. While suffering from uterine cancer in her 30s and breast cancer in her 40s, she raised four children. Her oldest son, Han Jeong Mi, 66, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, expressed his gratitude. “Because my parents themselves were not sufficiently educated, they probably wanted to push us to study despite us being poor,” Mr. Han said.

No talk about detailed memories

Quitting her cleaning job around 15 years ago, Ms. Baek now lives peacefully alone in her old and familiar house. She has 10 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren, and she said watching them grow has been her greatest joy. Mr. Han, who lives nearby, assumed the post of chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural second-generation Korean A-bomb survivors’ association in 2015, with the aim of supporting A-bomb survivors and second-generation survivors.

On July 9, Ms. Baek visited Honkawa Elementary School at the school’s request for the first time since the atomic bombing. Although she spent about an hour looking around the school, including the museum renovated from the former school building, she did not speak about her detailed memories of that time. When Mr. Han, who was accompanying her, saw her leaving the school with a cane in her hand, he empathized with her. “As she doesn’t have any good memories, she might have erased her recollections of the school.”

Keyword

Honkawa Elementary School

The school first opened its doors in 1873 under the name Zoseisha. The first ferroconcrete school building among public elementary schools in Hiroshima City was completed in 1928. The building, configured with three stories aboveground and one portion underground, featured a series of arched windows. It was designed by Kiyoshi Masuda, who also was involved in designing the Taishoya Kimono Shop (present-day Rest House) and the former Hiroshima City Hall. Located 410 meters from the hypocenter, the school lost around 400 students and 10 teachers and school staff members in the atomic bombing. The day after the bombing, the school was turned into a temporary relief station; in February 1946, classes resumed. A peace museum in the school, which preserves part of the A-bombed school building, was opened in 1988. That museum is scheduled to be renovated and reopened in November 2026 as an exhibit facility affiliated with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward.

(Originally published on July 24, 2024)