Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: August 13, admitted to Fukuya Department Store, died at home

Aug. 13, 2024

Asked his family to look after his daughter, Yoriko

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

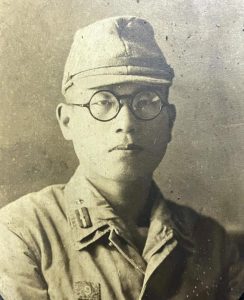

On August 13, 1945, one week after he experienced the atomic bombing, Masanori Miyatani, 28 at the time, died at his home in Onomichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture, despite the desperate care provided by his family. Mr. Miyatani had suffered serious burns to his back and head.

His only daughter, Yoriko, now 80, who is a resident of Onomichi City, has no memory of her father’s death because she was only one at the time, but she was told the story by her late mother and others. “I heard that before he died he had said, ‘Look after Yoriko’ to our family, who had gathered around him.”

Before the war, Mr. Miyatani was a teacher at Onomichi Commercial School (present-day Onomichi Commercial High School, in Onomichi City). He taught classical Chinese and judo, a sport in which he had been engaged since junior high school.

Drafted into the military, he was assigned to the Chugoku District Military Communications Reserve Corps in the area of Motomachi in Hiroshima City (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). On August 6, he was exposed to thermal rays from the bombing near Hiroshima Castle. He was admitted to the burned-out Fukuya Department Store, a reinforced, ferroconcrete building that remained standing after the bombing at its location in the area of Ebisu-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) in the downtown of the city. A photo taken on August 10 by Hajime Miyatake, a member of the photo department at the Asahi Shimbun Osaka head office who died in 1985 at the age of 71, shows wounded people with bandages around their head and arms lying packed together on the floor.

”Kill me,” he said repeatedly

On August 11, five days after he experienced the atomic bombing, Mr. Miyatani’s acquaintance informed his family in Onomichi City that he was at Fukuya. His father, Shikaichi, and his wife, Setsuyo, headed immediately to Hiroshima by train, arriving at Hiroshima station late at night the same day. Setsuyo carried Yoriko on her back.

The next morning, Shikaichi looked for his son in Fukuya, shouting out, “Masanori, where are you?” He found his son lying on the dusty floor. Diarrhea had swept through the patients admitted there, and an 18-liter metal drum had been placed nearby to serve as a toilet. Shikaichi pleaded with a truck driver passing outside the building to take them to the train station.

Mr. Miyatani was taken home by the end of the day on August 12 and, in great pain, he asked his family time and again, “Please kill me.” His jacket, stuck to his burned body, was cut off by a pair of scissors, but despite the bandages wrapped around the affected area, his wounds continued to bleed.

Too frightened to approach

“Even though my father would call out to me ‘Yoriko,’ I apparently didn’t understand what was going on and was too frightened to approach him… ,” explained Yoriko. She still feels grief to this day. A piece of paper that had been placed on his head in Fukuya, containing the words “Burns to the back” and other comments, ultimately became a memento by which he was remembered. Each August 6, his family brings water to the grave for Mr. Miyatani, whose dying message to them was, “Bring lots of water to my grave.”

Fukuya, where Mr. Miyatani had been admitted, was turned into a “provisional infectious disease hospital” that provided care mainly to A-bomb survivors suffering from such symptoms as diarrhea and bloody stool. The location was used in that way because the patients were diagnosed with acute infectious colitis, also known as dysentery. “Bulletin No. 8” released by Japan’s Army Ministry survey team, consisting of teachers from the Army Medical School in Tokyo and dispatched to Hiroshima to confirm the damage to the city, also indicated that, “There is currently an intermittent outbreak of dysentery in Hiroshima City.”

Sometime later, it was recognized that diarrhea and bloody stool, which initially broke out soon after the bombing and persisted until two weeks later, were obvious acute symptoms of A-bomb radiation.

(Originally published on August 13, 2024)