My guidepost, Hiroshima pioneers: Tomoki Deyama, 53, NHK announcer—Kiyoshi and Ikimi Kikkawa

Jan. 16, 2023

tyle="font-size:106%;font-weight:bold;">Couple conveyed anger of “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1”

Since joining the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) 31 years ago, Tomoki Deyama has reported on daily news and topics. This is his “unexpected” fourth stint at the local Hiroshima bureau. The city has since become a familiar place to him.

The A-bomb Dome was registered as a World Heritage site in 1996, the time of his first assignment to the Hiroshima bureau. When he heard that high school students in Saitama Prefecture were working to create a model of the A-bomb Dome, he contacted them to see if they would like to be interviewed. They were struggling with the assignment because they did not have much knowledge about the dome. He set about looking for an atomic bomb survivor who was familiar with the dome. That is how he met Ikimi Kikkawa (1921-2012). She was “slight but energetic when speaking.” It was then that he began interacting with Ikimi as well as the students.

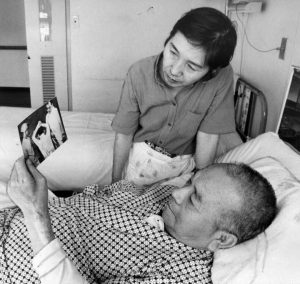

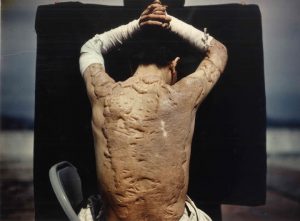

Ikimi had been married to Kiyoshi Kikkawa (1911-1986), the man dubbed “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1.” Both in Japan and overseas, Kiyoshi would call out the cruelty of the atomic bombing and express the anger felt among survivors by revealing the keloid scars on his back. After Kiyoshi died, Ikimi would share their A-bomb experiences with younger generations while showing listeners a photograph of Kiyoshi’s back.

Mr. Deyama said that he “learned about the couple’s journey through Ikimi.” Mr. and Mrs. Kikkawa experienced the atomic bombing at their home, about 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. Kiyoshi suffered severe burns and was admitted to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & the Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital), where he was labeled “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1” by a team of American journalists and scientists who saw the keloid scars covering his back. Since that time, the term has become synonymous with his name.

In 1951, after his discharge from the hospital, he opened a souvenir stand near the A-bomb Dome where he sold picture postcards and other items. If asked, he would also show his scars. Some accused him of taking advantage of the atomic bombing, but in response, he would explain his feeling that it was necessary to make people understand the horrors of the atomic bombing. At a time when there was no assistance available for A-bomb survivors of any kind, he paid visits on foot to other survivors, who were suffering from the aftereffects of their experiences in the atomic bombing combined with dire poverty. He formed an A-bomb survivors’ organization called the Rehabilitation Group for A-bomb Survivors. He proved to be a pioneer in the A-bomb survivors’ movement.

Touched by “her forceful words when she talked about Kiyoshi,” Mr. Deyama visited her home many times and became like a son to Ikimi, who had no relatives to depend on. Through his regular communication with Ikimi, he said he was able to gain a more nuanced and details view of the situation in which survivors found themselves and what assistance for them was required.

One day, Ikimi explained to Mr. Deyama how she came to know Kiyoshi. They first met at a get-together designed to lead to an arranged marriage. “I fell in love with him the moment I saw his back.” She was attracted to his broad back, which she saw when they were about to part, feeling that a man with a strong back like that would be able to protect her. “It was at then that I sensed them as two human beings,” said Mr. Deyama.

Ikimi often asked Mr. Deyama to “tell people about us.” Because his dream was to become a movie director, he convinced himself he would be able to keep a record of Ikimi’s words and the lives of the couple through the creation of a film. He was ultimately able to independently produce the film titled “The Back of Destiny,” which was released in 2009, on days off from his regular job.

He used a shot of Ikimi speaking to children in front of the A-bomb Dome as the closing scene of the film, in the hopes of conveying the couple’s wishes that “no one else should ever have to suffer the same fate.”

Each time he is assigned to the Hiroshima bureau, he is ever more keenly aware of the aging of the survivors. Ikimi no longer was able to testify about her experiences to the public by the time the movie was completed. She died in 2013 at the age of 92.

Mr. Deyama, concluding that it was up to him to pass on their story, is planning an event to inform the public about the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Kikkawa by reproducing the stall-like souvenir shop they opened beside the A-bomb Dome as he continues making films about the atomic bombing. He also works to encourage his younger colleagues to join him in communicating messages from the A-bombed city.

Ikimi followed in the footsteps of her late husband and continued speaking about their A-bomb experiences with a strong sense of responsibility. “I am willing to die while telling our story,” Ikimi would say. Mr. Deyama intends to continue conveying the wish she entrusted to him.

Born in Kobe City, Tomoki Deyama graduated from Kanazawa University. Since starting work at Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) in 1992, he has served as an announcer at local stations in Hiroshima, Wakayama, Osaka, as well as at the company’s Tokyo head office. Mr. Deyama has independently produced films such films as Hiroko-no-Nikki (in English, ‘The diary of Hiroko’) in 2022, the story of Hiroko Kajiyama’s journal, which inspired the launch of the campaign to preserve the A-bomb Dome. He currently lives in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward.

Kiyoshi Kikkawa visited other A-bomb survivors to learn about their living conditions. In 1951, he and others together founded the Rehabilitation Group for A-bomb Survivors, with the aim of improving the lives of survivors suffering from illness and dire poverty. In 1952, Mr. Kikkawa, along with the poet Sankichi Toge and others, established the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association, a group that called for medical and livelihood assistance for A-bomb survivors. His efforts from early on led to the founding of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations in 1956.

(Originally published on January 16, 2023)