Seiji Ozawa and A-bombed Hiroshima, Part 1: Imbued his conductor baton with sense of urgency about nuclear issue

Aug. 6, 2024

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

<br><br>

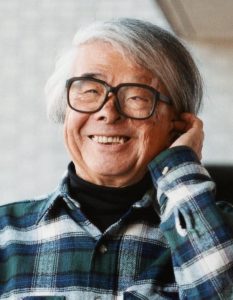

Conductor Seiji Ozawa, who worked with renowned orchestras worldwide and died on February 6 this year at the age of 88, performed music in memory of war victims both in Japan and overseas during his lifetime. What lay behind his passion? This series of articles traces the legacy that “Ozawa of the world” left behind in the A-bombed Hiroshima.

<br><br>

<div style="font-size:106%;font-weight:bold;">Affected by his uncle’s A-bombing experience</div><br>

A-bomb survivors whose hair had fallen out, and Hiroshima’s completely devastated cityscape… In December, 1973, Mr. Ozawa visited Peace Memorial Hall (present-day East Building of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum), located in the city’s Naka Ward, together with his mother, Sakura. In March last year, 2023, five photographs that capture Mr. Ozawa staring intently at the exhibits were discovered at the Toho Gakuen Hiroshima Music School for Children, located within the Hiroshima Christian Church in Naka Ward, during the music schools’ relocation.

<br><br>

In an interview with the Chugoku Shimbun published in the newspaper on January 19, 1975, Mr. Ozawa talked about how shocking his visit to the museum had been. “What impressed me the most were the horrors I saw in the Peace Memorial Museum. I didn’t think it would be as bad as it was.” He added, “I thought at the time that everyone in Japan should see the exhibits and Americans, especially politicians, should visit the museum at least once.”

<br><br>

Mr. Ozawa traveled around the United States and Europe during the Cold War between the United States and the former Soviet Union, an era marked by continuous proliferation of nuclear weapons. There was a program from that time that revealed his growing sense of urgency about how “nuclear weapons must never be used again.” On August 8, 1976, at the world-renowned Salzburg Festival of music, Mr. Ozawa conducted the Saxon State Orchestra Dresden in a performance of “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima” by Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki.

<br><br>

Dresden, too, was a city that had been destroyed by indiscriminate bombing during World War II, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians. Yuichi Iwano, 59, a music journalist in Tokyo, surmised, “Mr. Ozawa was a pure-hearted person. I think his tour of the Peace Memorial Museum compelled him to perform that piece.”

<br><br>

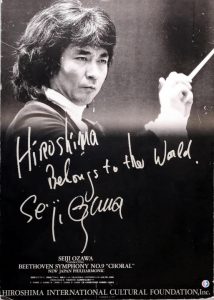

During the period from the 1970s to the ‘90s, Mr. Ozawa performed more than 10 concerts in Hiroshima with orchestras from Japan and abroad. He conducted the San Francisco Symphony in June 1975, the Boston Symphony Orchestra in March 1978, and the New Japan Philharmonic in November 1982 in a passionate performance of Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 9” with 230 members of the public. In his message for that event, Mr. Ozawa wrote in English by hand, “Hiroshima Belongs to the World.”

<br><br>

On August 6, 1985, the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Mr. Ozawa visited Peace Memorial Park early in the morning. In front of the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, where the remains of around 70,000 people are kept, he sang hymns and children’s songs for about one hour in a choir made up of friends and acquaintances from his alma mater Seijo Gakuen Junior and Senior High School. Fumiyo Handa, 76, a piano teacher and a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward who was present at the event, recalled, “I felt Mr. Ozawa stood in sincerity with the A-bomb victims. His deep feelings for the A-bombed Hiroshima came through.” At a Boston Symphony Orchestra performance in Hiroshima the following year, he and members of the orchestra laid wreaths of flowers at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and vowed “to continue our anti-nuclear appeals throughout the world.”

<br><br>

Mr. Ozawa has another connection to the A-bombed Hiroshima — his paternal uncle Shizuka. His uncle had participated in a student orchestra led by a Russian émigré at Manchurian Medical University in what was then Manchuria (present-day northeastern China), and was the first person to introduce classical music to the Ozawa family (this, according to the aforementioned Yuichi Iwano). After graduation, Shizuka became a military physician, and on August 6, 1945, he experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima City, after which he set about treating victims of the bombing.

<br><br>

After the war, Mr. Ozawa starting playing the piano that Shizuka had left him and thus began his music career. His brother Toshio, 94, a resident of Kawasaki City, said that Shizuka later died of leukemia.

<br><br>

In the mid-1980s, Mr. Ozawa and associates from overseas attended a social gathering at the former Grand Hotel, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. Naoko Naganuma, a resident of the city’s Naka Ward who served as an interpreter at the gathering, said, “I cannot forget Mr. Ozawa as he made a tearful speech in English, saying the reason he kept coming back to Hiroshima to perform was because of his uncle’s experiences in the atomic bombing here.”

<br><br>

His final performance in Hiroshima took place in October 2005, the 60th year after the atomic bombing. Mr. Ozawa, who was 70 at the time, conducted Fauré’s “Requiem” at a peace event held at the Hiroshima Green Arena, located in the city’s Naka Ward. Norie Harada, 70, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward and president of the Hiroshima Prefectural Choir Association, served as the alto section leader of a civic choir group composed of around 440 members. The emotions of that day remained etched in her memory. She said, “Mr. Ozawa was energetic and had a magical aura. Led by his baton, all the participants came together as one, and the entire arena was filled with prayers for peace.”

<br><br>

<strong>Interview with Ozawa’s older brother Toshio — to Seiji it probably was “scary”</strong><br><br>

The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Toshio Ozawa, 94, Seiji Ozawa’s older brother and director of the Ozawa Folklore Research Center, about the A-bombing experiences of his paternal uncle Shizuka, a military physician, and the message he would like to pass on to future generations.

<br><br>

***

<br><br>

I think my uncle was about 40 years old at the time. He experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima City, after which the war ended. I heard he was in Ujina on the day of the bombing probably because he was off duty. That’s why he survived. I heard him say repeatedly, “There was a flash of light, and everything was gone in an instant.”

<br><br>

Because he served as a military physician, he was not allowed to leave Hiroshima even after the war ended. He would say, “Day after day I treated the wounded and applied oil to their burns.” I was a junior high school student when I first heard him tell of his experiences in the atomic bombing. Child as I was, I was very fearful that death was imminent (as a result of aftereffects from the bombing).

<br><br>

Seiji was a child, five years younger than I, so he probably heard our uncle’s experiences in his own way. Yes, in his own way. I suppose he thought it was “scary.” Our uncle died of leukemia after the war.

<br><br>

(In 1970s and ‘80s) I heard many stories about Hiroshima from Seiji. He was shocked when he visited Hiroshima and stood on the exact spot where the tragedy occurred. We four brothers were very close. I never thought he would die before me.

<br><br>

We know what life was like during the war. Nearly 80 years have passed since Japan’s defeat, but it still feels to me as if the horrific bombings happened just recently. I never went to battle, but I did make gunpowder “for the nation.” It frightens me that I never had any doubts about what I was doing. Japan put itself in difficult circumstances. I want people living today to learn the reality of our tragic history.

<br><br>

(Originally published on August 6, 2024)